Hacking Systems of Power with Glitter: Gretchen Andrew on Her Whitney Museum Acquisition

By Cansu Waldron

If you’ve been following the digital art world lately, you’ve probably heard the news: the Whitney Museum of American Art has acquired two works from Gretchen Andrew’s Facetune Portrait Universal Beauty series — a unanimous decision that marks a major moment not just for the artist, but for digital art’s evolving place in institutional collections.

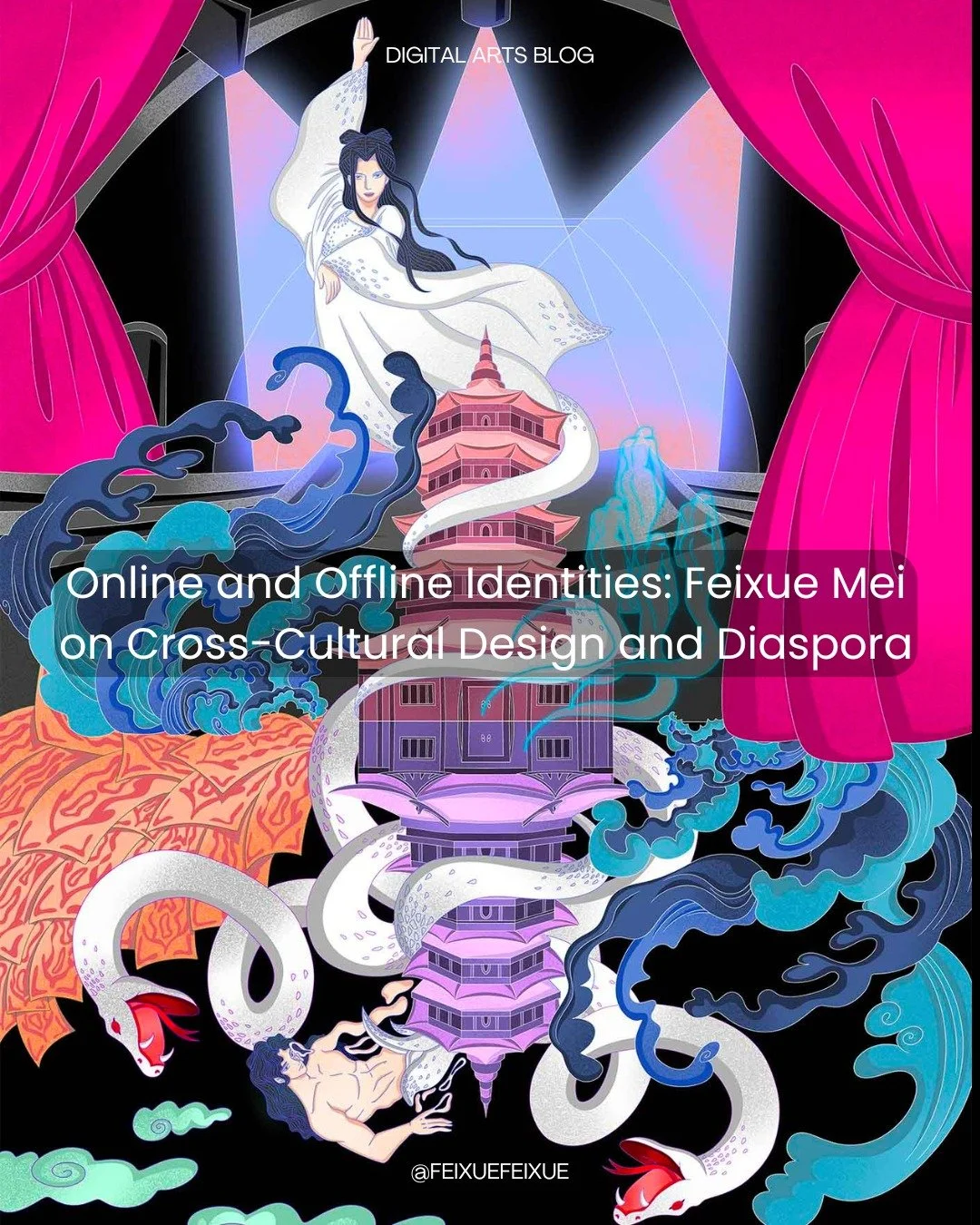

Known for “hacking systems of power with art, code, and glitter,” Andrew has long blurred the lines between traditional painting, internet performance, and technological critique. From her viral “vision boards” that hijacked Google search results to her powerful Facetune Portraits, her work continues to question who gets to control images, narratives, and visibility in the digital age.

For years, Gretchen has explored how power operates in both physical and digital spaces — from museums and beauty standards to search engines and social platforms. Her practice combines the raw tactility of paint with the logic of algorithms, revealing how deeply aesthetics and technology shape our sense of worth and truth.

The Facetune Portraits, in particular, expose the hidden systems of digital modification that define modern ideals of beauty, while reasserting the painter’s hand as an act of reclamation. As institutions like the Whitney begin to collect work born out of this intersection, it feels like a recognition that art made with (and against) technology can be both conceptually rigorous and emotionally resonant.

We spoke with Gretchen about the ideas behind her Facetune Portraits, how her “vision boards” redefined internet art, and what this moment means for her — and for digital artists everywhere.

Let’s start with Facetune Portraits. You’ve described them as a way to paint what technology tells us we should look like. What first drew you to exploring beauty filters as a subject?

I always seek to work with deceptively approachable subjects through which we can explore complex technologies and their implications. I am especially drawn to parts of feminine culture that are often seen as superficial or unserious, but which provide a rich playground for investigating the impact of technology in our lives. On a personal level, I was exploring the physical and metaphorical shapes we contort ourselves into when we feel we have to fill a role or behave a certain way. Everyone has experienced being told they are not enough or that they need to change to be accepted. That is what these works are about—coexisting with the gaps and tensions between who we really are and who we are told to be. Increasingly, we are told to be something different by AI.

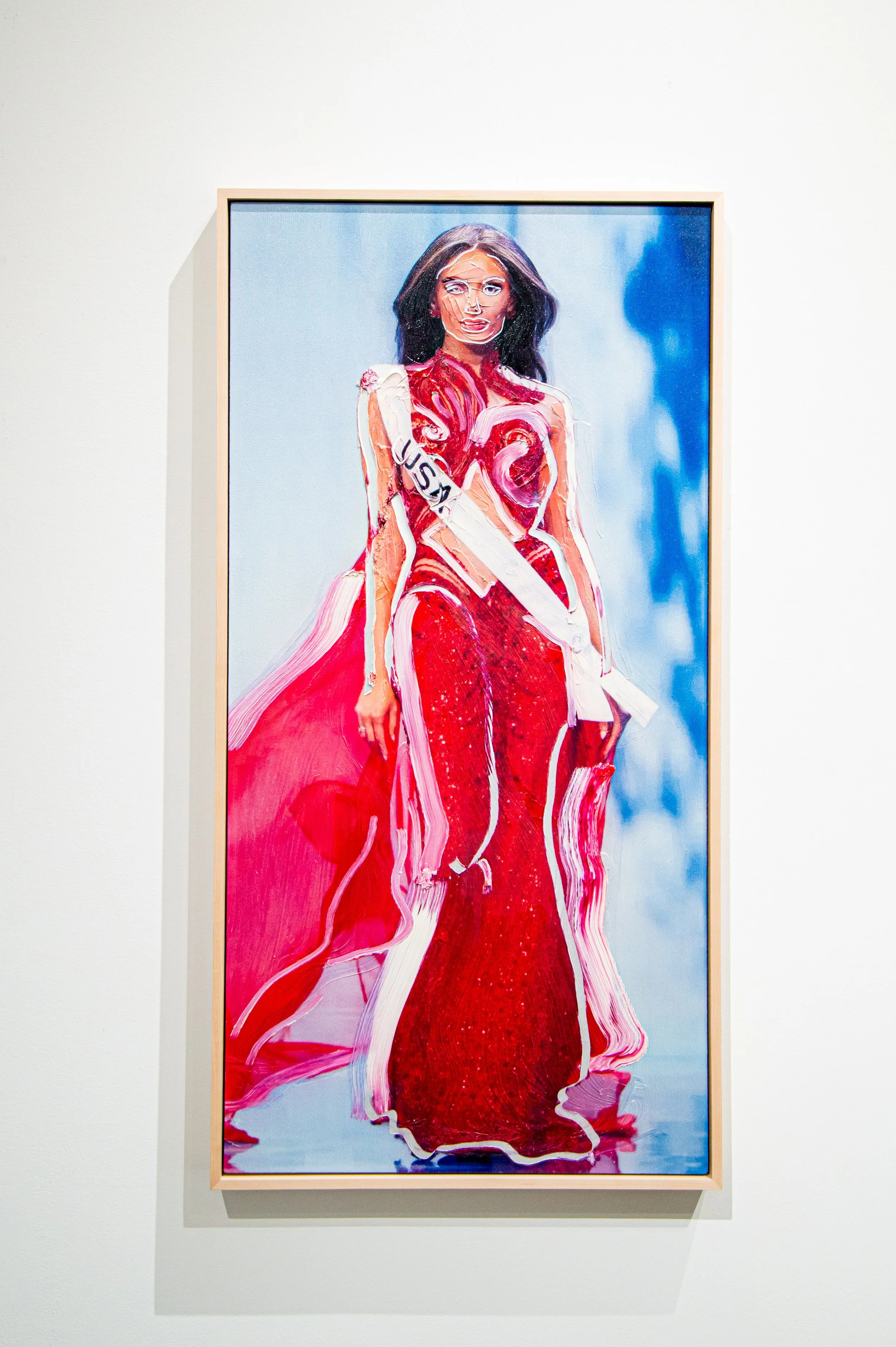

Facetune Portrait - Universal Beauty, Puerto Rico

48" x 24"

2025

Oil On Canvas

Gretchen Andrew

What emotions do you want people to sit with when they see these portraits in person?

I spent two and a half years in the technical and conceptual development of this work, but when I was in the studio making them for the first time, I was honestly shocked by the violence of it. Watching the robots scrape, carve, and scar the delicately perfect surface of the oil paint felt violating, especially as I was first experimenting with selfie photos. The experience of witnessing the works being made is not essential to their meaning, but that aggression remains within the absurdity. Curiosity is always the widest door, and I have also observed both outrage and laughter in response. There is something unsettling about them, yet that tension draws people in.

Your use of custom robotics to paint filtered images back onto canvas is fascinating. What does it feel like to collaborate with machines to literally share authorship with technology?

The robots are really quite dumb. Like AI-driven filters, they simply do what they are told, in this case making changes to an image made of paint based on what the digital filter would have done. When a filter moves pixels around, it is invisible, but when the robot does the same thing in paint, it creates marks and scars. I act almost like the robot’s conductor, changing speed, pressure, and brushes to achieve the kind of mark-making I want. I do not feel like I am collaborating with the technology so much as battling it. Certain elements are fixed, such as the shape the AI imposes on the body, but other aspects of traditional mark-making remain entirely within my control. I use those choices to create a beautiful, and often grotesque, image.

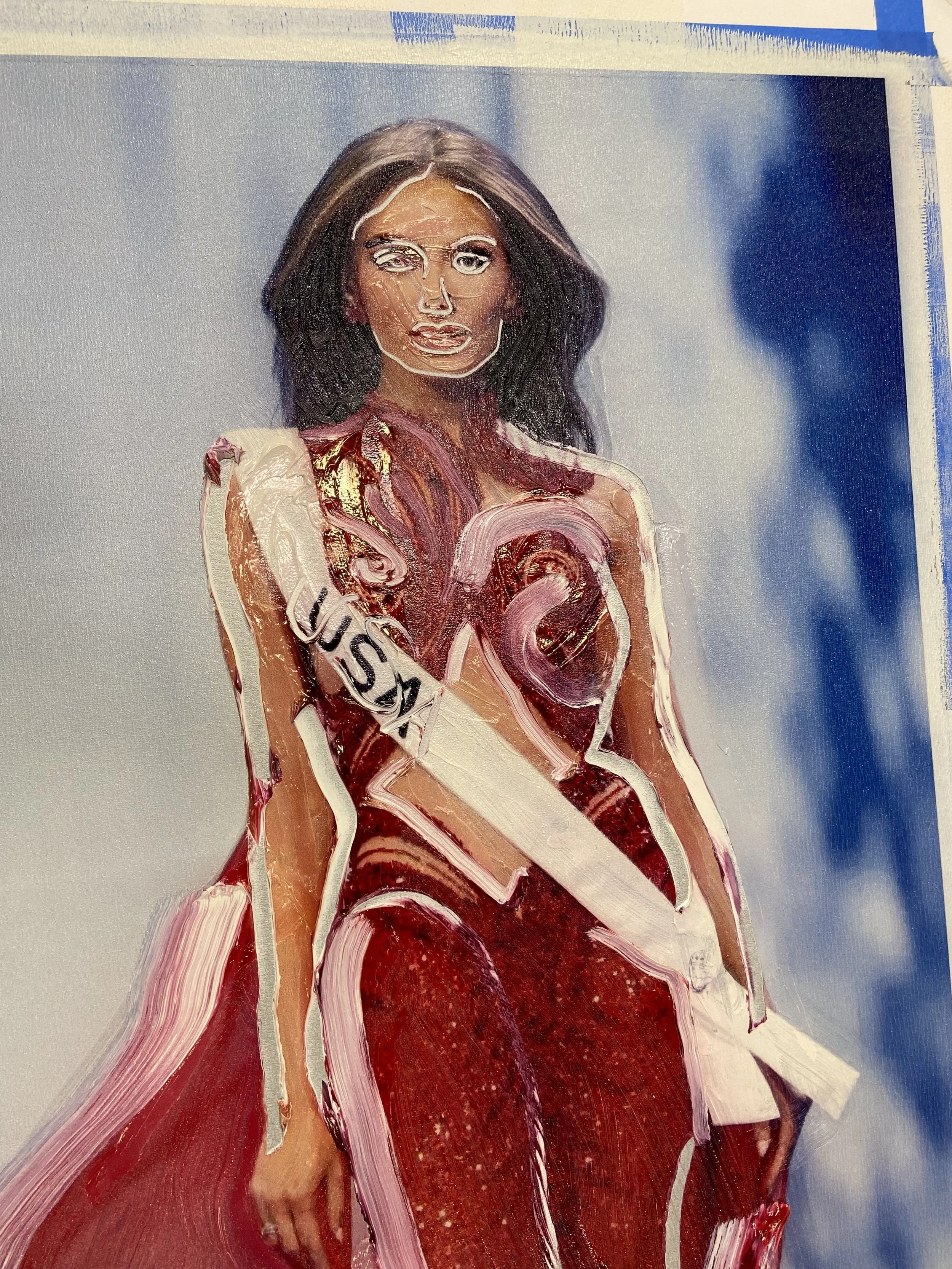

Facetune Portrait - Universal Beauty, USA

48" x 24"

2025

Oil On Canvas

Gretchen Andrew

The Whitney Museum recently acquired two Facetune Portraits. That’s a huge moment, not only for your career but for digital art entering institutional space. How did that acquisition feel, and what do you think it says about where we are culturally?

When I decided to become an artist, I was very clear about what kinds of success mattered to me. I wanted to enter the canon of art by both joining certain traditions, such as painting and portraiture, and twisting them into forms that are as unique to me as they are to this cultural moment. Portraiture has always reflected a combination of what is technically possible in a given era and how people want to see themselves. Oliver Cromwell famously asked to be painted with all his warts to show that he was humble and straightforward, in contrast to his gilded predecessors. The filtered image reveals how much we value conformity and how deeply we fear being truly seen.

You taught yourself art through YouTube tutorials. Do you still think of yourself as a “self-taught hacker,” or has your relationship to that identity evolved as your work enters major museums?

It always makes me laugh that the art world considers me self-taught. I graduated with honors from a top university, had the entire internet to learn from, and have had incredible studio apprenticeships with artists like Billy Childish, Penny Slinger, and Derek Boshier. Nothing about that wealth of knowledge is self-taught, though it is certainly self-directed. I am also very aware that what took me and my work from A to B will not take me from B to C, and so on. What I need to learn and who I can learn it from is always changing.

Glitter has become a signature in your practice, both as material and metaphor. What does it symbolize for you now?

Glitter to me is a simple way of saying “everyday magic.” It is also insidiously difficult to get rid of. Use it once and it will haunt your pillowcases and show up on your yoga mat for months. I think my work and I are a bit like that too.

Your early “vision board” projects literally rewrote how search engines saw you, inserting yourself into the art world’s digital hierarchy. Can you tell us about how it all came together?

Both the Vision Boards and the Facetune Portraits deal with how much inherent trust we place in photography as having a stronger relationship to truth than other artistic mediums like painting, which we know to show “a truth” rather than “the truth.” I realized that search engines are built entirely on relevance, and that by making my artwork relevant to certain art-world institutions, Google would conflate that in the same way René Magritte played with the relationship between image and language in The Treachery of Images. By repeatedly stating online that I wanted my paintings to be on the cover of Artforum, Google eventually came to understand that my paintings were relevant to the search “cover of Artforum” and began surfacing them at the top of that query.

What’s a fun fact about you?

I’ve run at least a mile every day since 2007. I once had to do this while at the Dubai Art Fair. You can ask Georg Bak. It was 11 p.m., we were still at the party, and I realized I hadn’t done my mile yet. I disappeared for about ten minutes and came back a little sweaty. It is one of the reasons I am almost always wearing either Birkenstocks or Sneex. I can get through a mile in both.

What else fills your time when you’re not creating art?

I am passionately unskilled at piano, golf, and speaking Japanese.

Finally, what kind of “hack” are you dreaming about next?

I am using the same conceptual and technical process of physical photo manipulation in paint to explore AI-driven apps that make us look younger, and also those that turn any photograph into deepfake pornography. Both are crucial conversations and are already resulting in powerful, if somewhat disturbing, paintings.