A Fossil Record of Early Human Thought: Joe Banks on Where Language Becomes Technology

By Cansu Waldron

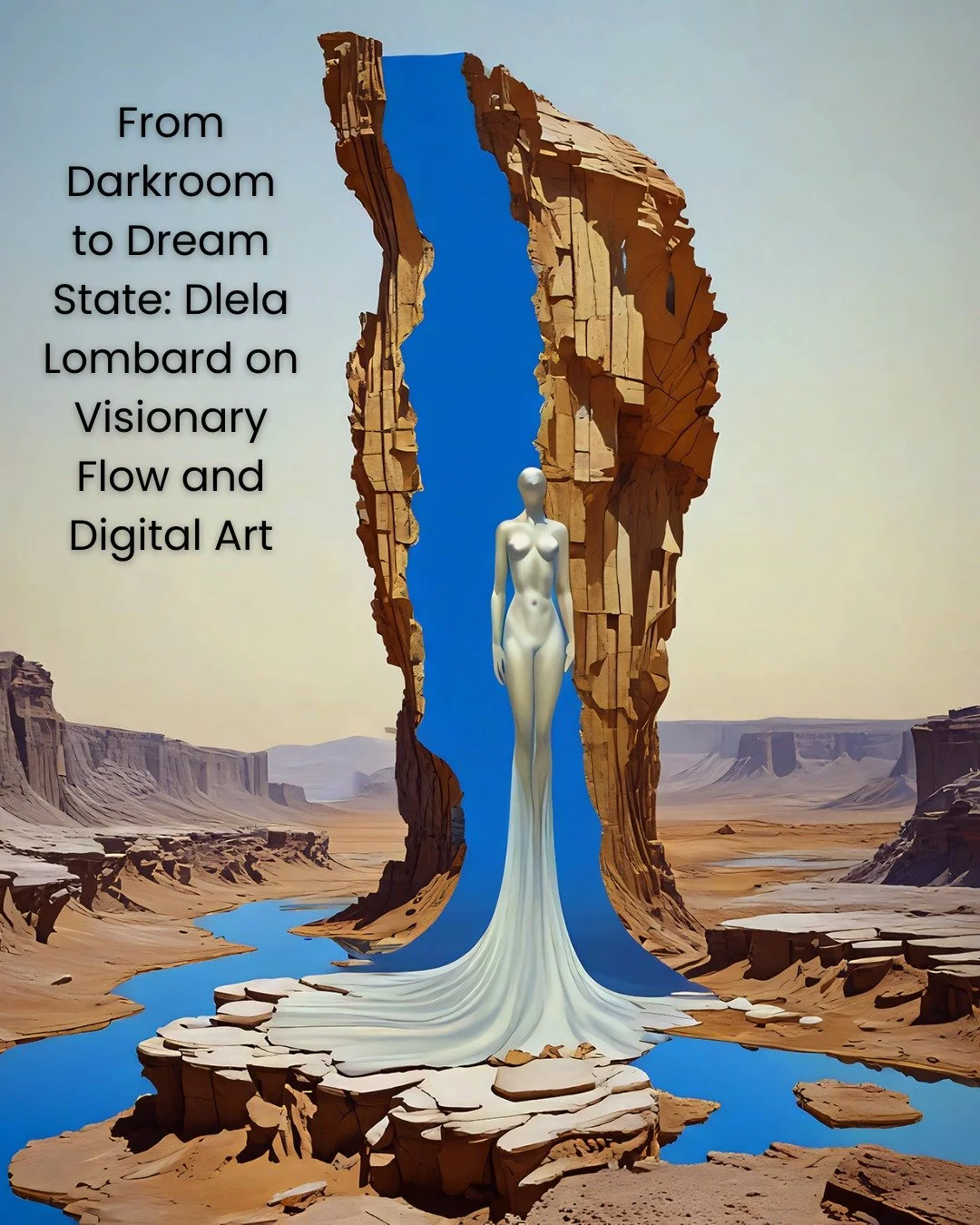

Joe Banks is an installation artist, researcher, and electronic musician behind the long-running project Disinformation. His work centers on electricity, communication, and language — often taking the form of electromagnetic sound pieces and audio-visual illusions. His latest piece, Language [as] Meta-Technology, pushes this inquiry further by challenging narrow definitions of what “counts” as language. Rather than limiting language to human syntax or computer code, the work proposes that language is everything we use to communicate — across species, histories, and technologies.

Seen through that lens, language becomes the foundation that makes all other technologies possible. Banks points out that even something as “simple” as a shovel requires accumulated knowledge of timber, fire, metallurgy, ergonomics, agriculture, and shared techniques — skills that could only emerge through social communication. While individuals can learn through observation and trial-and-error, the collective evolution of tools depends on communities speaking, teaching, and organizing. In this way, Language [as] Meta-Technology suggests that language isn’t just another tool in human history — it’s the underlying system that enables every other tool to exist.

We asked Joe about his art, creative process, and inspirations.

Disinformation, Spellbound, Montage, 2000.

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

The art project I produce - Disinformation - started out as an electronic music project, albeit highly esoteric, so closer to what we now call sonic art, and, within 2 years of starting, became involved in exhibiting video and installation art. From the outset, I was working with DCC (Digital Compact Cassette), which was a cheaper alternative to the (industry standard) DAT (Digital Audio Tape) format; I borrowed a Mini-DV (Digital Video) camera, for making the “Spellbound” video artwork; and, before starting Disinformation, I’d gone halves with (photographic re-toucher) Jamie Register to buy an AppleMac computer, so Disinformation was designing semi-professional digital graphics, like the diamond-shaped cover artworks for the Disinformation “R&D” (“Research & Development”) CDs.

It’s also worth mentioning that early Disinformation products were released on (vinyl) LP and (digital) CD, (mostly) published by the experimental music label Ash International. CDs were cheaper to produce and more expensive to buy than vinyl, so, if you had a label, willing to cover manufacturing costs, then digital media enabled independent or DIY producers to turn a modest profit on small print-runs, of what would previously have been considered totally non-commercial audio art. Disinformation specialised in exploring the creative potential of electromagnetic noise, so that opened a window-of-opportunity in terms of establishing Disinformation as a viable art project.

Disinformation, R&D CD Artwork, 1996.

What events do you consider to be milestones in your digital art career?

The “Language [as] Meta-Technology” sound artwork was first exhibited at Sluice HQ (art space) in 2018, in a Disinformation solo exhibition curated by Julie F. Hill. With a great deal of experimentation, I’d found a way to persuade a digital piano to produce an infinitely repeating, Möbius-type loop, then used a high-end software speech synthesiser, to render the text-to-speech content. In 2021, “Language [as] Meta-Technology” was physically exhibited and published on-line as a QR code, which routes through to a MP3 audio file of the “Language [as] Meta-Technology” sound artwork, which has, so far (Nov 2025) been downloaded 11,000 times.

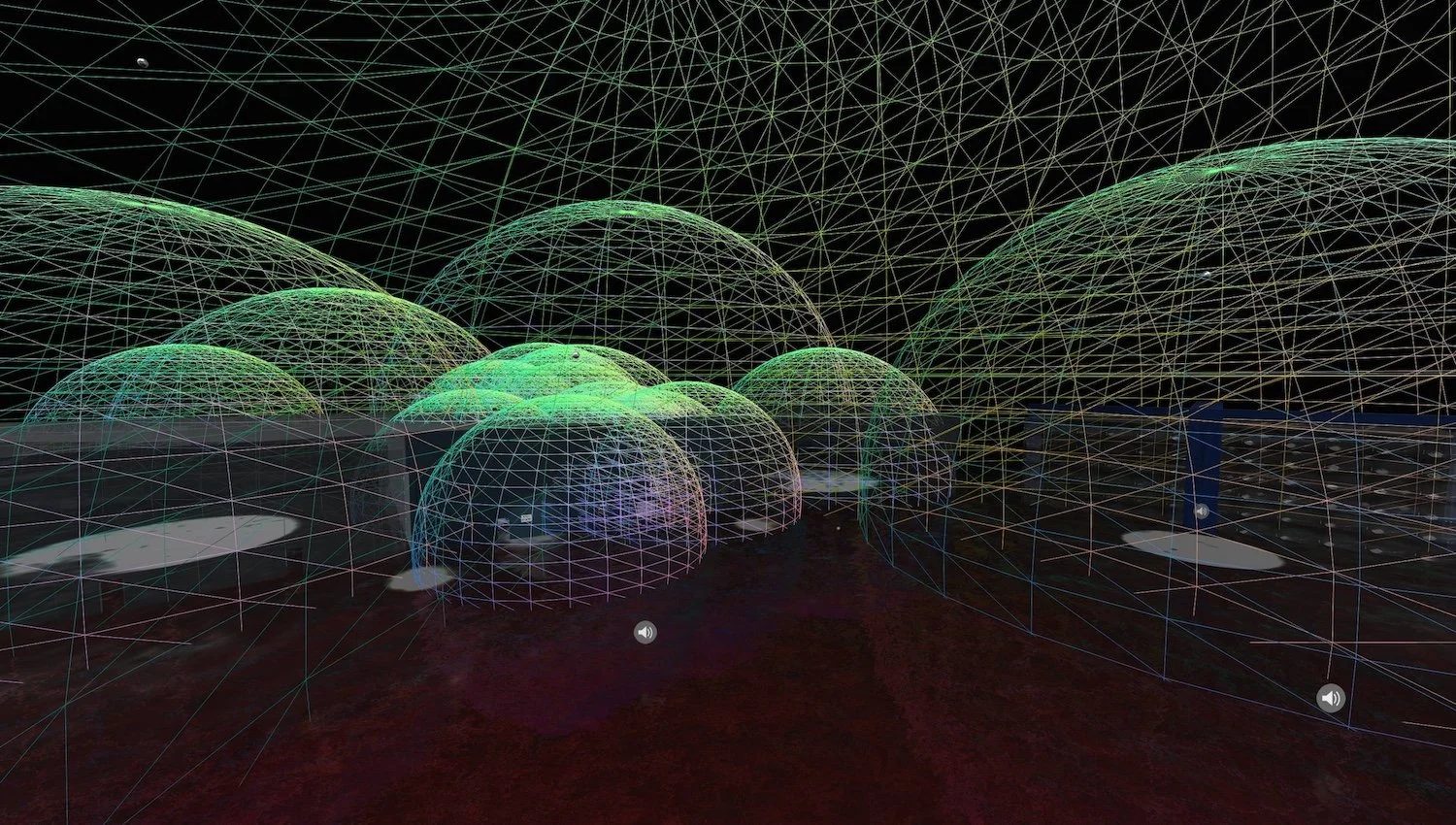

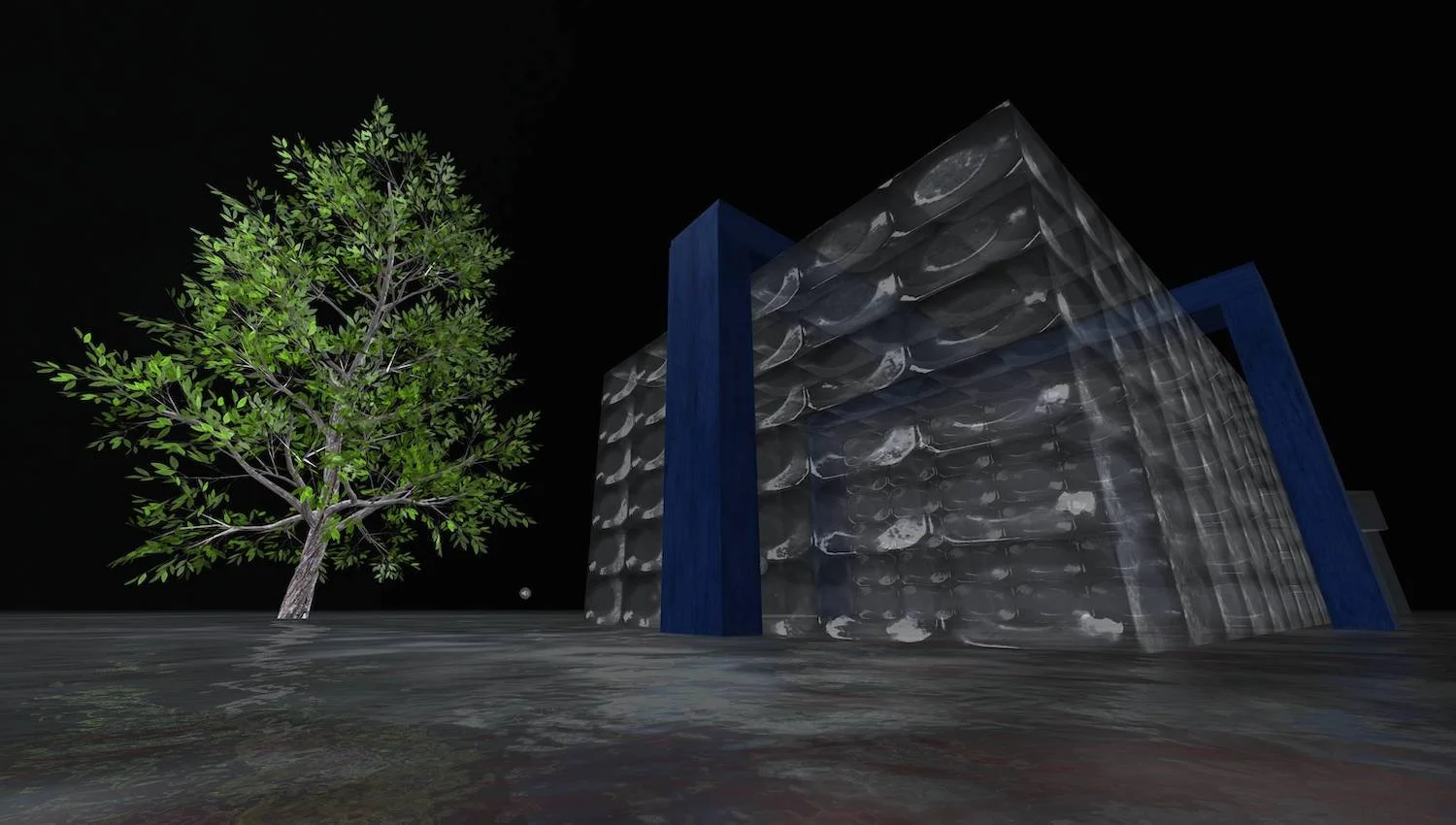

In 2022 Schemata Arts, which is the digital arm of the London nightclub Corsica Studios, with the online exhibition platform New Art City, hosted “Antithesis” by Disinformation, which is a permanent exhibition of electromagnetic sound art. “Antithesis” is designed in such a way that a three-dimensional online environment becomes a form of spatial remix engine, whereby visitors can remix the audio content by navigating the virtual space. The real Corsica Studios is located in London’s Elephant & Castle, close to the spectacular so-called “Brutalist” memorial to the electrical scientist Michael Faraday, and “Antithesis” curator Alice Hoffman-Fuller designed a 3D model of the Faraday Memorial, with the central concept of “Antithesis” being that the electrical infrastructure of London is in itself a form of creative artwork.

Disinformation, Language as Meta-Technology, 2021.

The phrase “Language is Meta-Technology” is such a powerful starting point. How do you see language shaping or containing all other technologies?

The communications theorist Colin Cherry argued that computer languages aren’t (in technical terms) real languages, just as Noam Chomsky (among others) claimed that animal vocalisations can’t be considered real language, because the latter aren’t (allegedly) syntactical. In contrast, the “Language [as] Meta-Technology” artwork expresses, or (at the very least) strongly implies, the view that “real” language absolutely includes EVERYTHING that the word “language” can reasonably be used to refer to.

So, as a work of genre text and language artwork, “Language [as] Meta-Technology” refers to EVERY form of historic technology - from animal to early human vocalisations, and the origins of complex speech, in co-evolution with Paleolithic tool-use, to pictographic and ideographic writing, to numeracy, alphabets, literature, craft and then industrial technology, printing, programming languages, AI and large-language models.

In that sense it’s pretty obvious that the “Language [as] Meta-Technology” QR code is a medium that’s appropriate for this particular message; however, in an exchange of e-mails with the artist Jim Andrews (“Enigma N^2022” etc), Jim questioned the assertion that (quoting the artwork’s subtitle) “language is the technology that contains ALL others”. After some thought, the example I gave was that manufacturing even basic technology like a common-or-garden shovel, involves, in that case, a sophisticated knowledge of ergonomics, woodworking skills, agriculture and metallurgy.

In order to actually make a shovel from scratch, a community needs to, firstly, co-operate, then to receive and share information about the identification, cutting, drying, shaping and steaming of different types of timber, hence also about fire, about mining, and the smelting, working and physics of ores and refined metals; while the shapes of the handle, stem and blade entail detailed knowledge of the human physique and organised agriculture. So, while a little of that knowledge might be obtained by observation and mimicry, luck and trial-and-error, etc, en-masse these skills are way beyond the reach of any isolated individual, and can only have emerged from socially complex communications. In other words, to have evolved even basic tools, people MUST have spoken to each other.

Disinformation, Language as Meta-Technology, 2018.

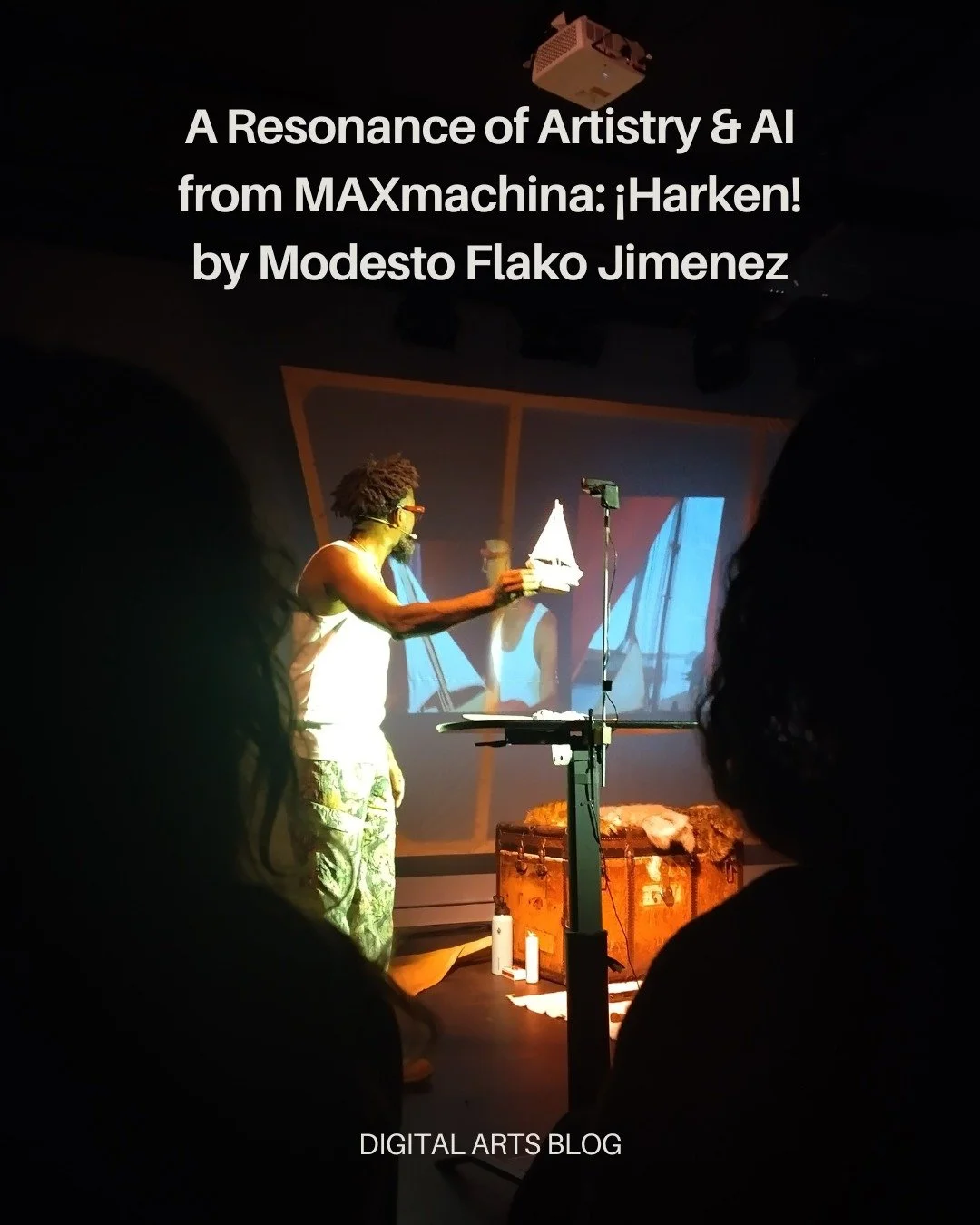

You’ve recently exhibited at Outernet Arts, Europe’s largest digital exhibition space. What was it like to experience your work in such an immersive, high-tech environment?

Outernet is described as “London’s most visited tourist attraction” by The Times newspaper, and as the “world’s largest LED screen deployment” by City AM. Notwithstanding Circa Arts (in Piccadilly Circus), which is out-of-doors, there are several LED video spaces in London - Outernet Arts (Tottenham Court Road), Lightroom (King’s Cross), W1 Curates (Oxford Street) and Frameless (Marble Arch), etc; and, in terms of re-shaping the landscape of public art and the built environment, VIDEO is increasingly becoming part of ARCHITECTURE.

What’s unique about Outernet however is that Outernet use advertising to cross-subsidise exhibits like “Ammonite”; so, while the building casts the LED screens into shadow, rather than total darkness, meaning that the blacks in “Ammonite” still look really black, the spaces are open and visitors can just wander in, admission free. The secret weapon for “Ammonite” was the (“Rorschach Audio”) soundtrack, with the immersive depth coming from combining this dream-like audio with the impression, when you're watching the twin spirals of the “Ammonite” videos, that you’re being fixated by an enormous pair of glowing EYES.

Disinformation, Ammonite, Outernet, 2023.

In “Ammonite” you draw on both sound and fossil imagery. What drew you to that connection between ancient biological forms and sonic memory?

“Ammonite” emerged from (technically very basic) experiments with the Mini-DV camera, refined however to an absolutely minute level of technical precision. As it happens, my mum’s an archaeologist and our grandad loved collecting fossils, so, when these gorgeous spirals started emerging, that was the association I made and the direction I pushed it in. In 2016 I gave a talk at Anglia Ruskin University Art Gallery, where I said that language itself contains a “fossil record of early human thought”. While most of the soundtrack for “Ammonite” is this blissfully soft musical ambience, every 15 minutes there’s a burst of distorted communications chatter - like police or military radio; it’s simulated, using digital software, but this sudden burst of discordant speech sounds works as a really effective contrast to the dream-like ambience and the hypnotic effect of the spirals.

Disinformation, Ammonite, Sluice HQ, 2018.

Your work sits at the crossroads of philosophy, technology and sound. When you think about the future of sonic art, what directions feel most urgent or exciting to you?

Ideas about relationships between language and technology have become relevant to the point of being literally weapons-grade in context of AI, when large language models are now used to target weapons systems that actually kill people (albeit, allegedly, with human oversight), where AI is being weaponised to spread political disinformation, and AI is exacerbating the mental-health crises caused by social media addiction. So, sorry to focus on the negatives, but, in terms of social relevance, “Language [as] Meta-Technology” landed at just about the right time in that respect. The core message of “Language [as] Meta-Technology” is the idea that people who DON’T have access to massive resources still have access to LANGUAGE, and that language is, paradoxically, the most fundamental and, at least potentially, the most powerful form of technology. At the point where philosophy becomes politics, the idea is to try to encourage people to see language not in terms of its limitations, but as a weapon of self-empowerment.

In terms of what kind of sound art might emerge next, I have no idea, though core Disinformation repertoire has always focussed on extreme economy of means - low budgets, big ideas; and, because the focus is on ideas, the manifestations of those ideas scale-up, eg - from pro-bono online publications to large-scale installations and exhibitions etc.

Disinformation, Ammonite, Outernet, 2023.

What is a fun fact about you?

Well, it’s not my story, but it’s a GOOD story - my uncle Eddie [RIP] worked as what he always described as an “electrician” for G.C.H.Q., the UK government communications agency. For reasons of military secrecy, he never talked about his work, until, shortly before he died, aged 100, he started talking. In the mid-1950s Eddie worked on secondment from G.C.H.Q. to Operation Gold in Berlin, where the CIA and MI6 tunnelled under the Berlin Wall to tap into East German telephone cables - Eddie’s job was to wire up the banks of tape recorders; before that he worked with Alan Turing in Manchester, helping build the Pilot ACE, one of the world’s first electronic computers!

So, even apparently “dry” artworks like “Language [as] Meta-Technology” and “Ammonite” are highly personal, in that eg - Eddie was a communications engineer, my dad Colin [RIP] was a typographic designer, so, arguably, also a communications engineer, and my mum Caroline is a (retired) archaeologist. My dad was working class, disabled, and excluded from education, left school without any qualifications, and went on to design classic typefaces for Post Office Telecommunications and British Telecom, so this whole world of ideas about communications and tool use had a big influence on Disinformation artworks.

Disinformation, Antithesis, Sound Spaces

What is a dream project you’d like to make one day?

There’s more philosophy of language artworks I’m ready to exhibit. There’s also a new Disinformation strand called “Videostar”, which explores this hyper-saturated colour palette - evoking a cultural memory of the “golden age” of video - that’s heavily romanticised and mythologised in contemporary culture (notably with Netflix productions like “Stranger Things” and “Archive 81” etc). Tony Tremlett (now director of TINA Gallery) curated “Ammonite” at Outernet, and pitched “Videostar” to a property company in the City of London. They liked the work, but needed something relating to land-use, so I didn’t get the commission. So, if any curators are interested in exhibiting “Videostar”, please get in touch!

Disinformation, Antithesis, Sound Spaces