Asemic Scores and Napa Cabbage: The Art of Sophie Ruoyu Zhang

By Cansu Peker

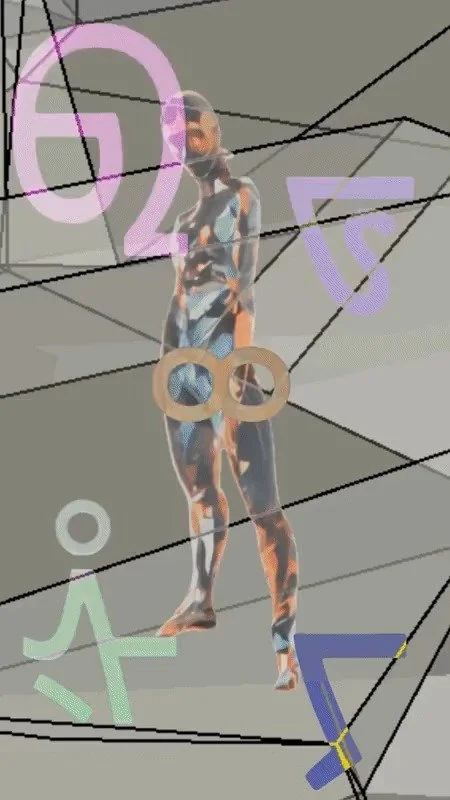

Sophie Ruoyu Zhang is an interdisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn, NY. With a BFA in Painting from the Rhode Island School of Design, her work explores the intersections of post-humanism, material ecocriticism, and asemic expression. Drawing from both traditional and digital media, she creates poetic systems like “scores” or “scripts” that blur the boundary between human language and the autonomous gestures of nature and machine.

Zhang’s artistic process is grounded in experimentation and deep research. During her time at RISD, she embraced a cross-disciplinary approach that incorporated sound, performance, and coding environments such as Max/MSP and Pure Data. Her practice reflects a desire to create symbiotic relationships between materiality and meaning, where digital and organic forms exist in dialogue rather than opposition. Through these layered explorations, Zhang builds conceptual landscapes that ask how we perceive, decode, and coexist with the more-than-human world.

We asked Sophie about her art, creative process, and inspirations.

Can you tell us about your background as an interdisciplinary artist? How did you get started in the digital art field?

I was born in 1999 in Chongqing, China. As an interdisciplinary artist, my creative journey has involved personal challenges and been deeply shaped by my environment. Coming from a family without an artistic background, applying to art school in 2019 was a significant hurdle for me. I spent my college life at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and my understanding and practice of art expanded and deepened. RISD’s interdisciplinary and exploratory curriculum allowed me to experiment with diverse media and deeply engage with contemporary digital technologies, sound, performance, and conceptual art. During this time, I began integrating digital software such as Max/MSP and Pure Data into my practice, and gradually built a holistic artistic approach that blends technology, materiality, and sensory experience.

Improvization seems to play a key role in your sound-based work. What role does unpredictability or spontaneity play in how you relate to your digital tools?

Take the example of pi—a symbol that recurs throughout some of my digital works. As an irrational number, it contains infinite possibilities; its radical randomness allows for combinations like “128” or “889” to naturally emerge, even sequences that might correspond to your birthday, my password, or any number of personally coded references. This seemingly romantic randomness gives us the illusion of something tangible—yet this “tangibility” is, in essence, a projection of human symbolic attribution onto numbers.

The concept of “improvisational” I explore is always situated within the framework of asemic arts. Whether it is numbers, brushstrokes, their material grounds, or sounds, sentences, and musical notations—their formation and presence are all shaped by the poetics and logic of asemic thinking. As one scholar notes, “Asemic arts are a form of writing that does not attempt to communicate any specific message, other than its own existence as writing… it is the shadow, impression, and abstract presentation of traditional script.”

In my view, painting and writing, musical scores and language, all begin from the same state—devoid of symbol, stripped of semantic value, reduced to pure rhythm. In my visual works, the asemic score manifests as a visible, literal rhythm; while in my digital-based performance and sound art, such scores are enacted and experienced through sensory and interactive means.

Many of your performances involve digital prototypes — could you tell us more about how you develop and use these tools in live settings?

In most of my performance works, I use digital tools such as Max/MSP and Pure Data. I don’t treat them merely as structural frameworks or instruments, but as dynamic systems of relational agency. These open-ended platforms allow me to construct environments where sound emerges through the interaction of human gesture, machine logic, and environmental feedback.

At times, the prototypes or systems I create even surprise me—they interrupt, respond, or behave in unexpected ways. That unpredictability is precisely what excites me. The performance becomes a kind of real-time dialogue between myself, the system, and the surrounding environment.

Can you tell us about some of your favorite pieces or a past or upcoming project? What makes them special to you?

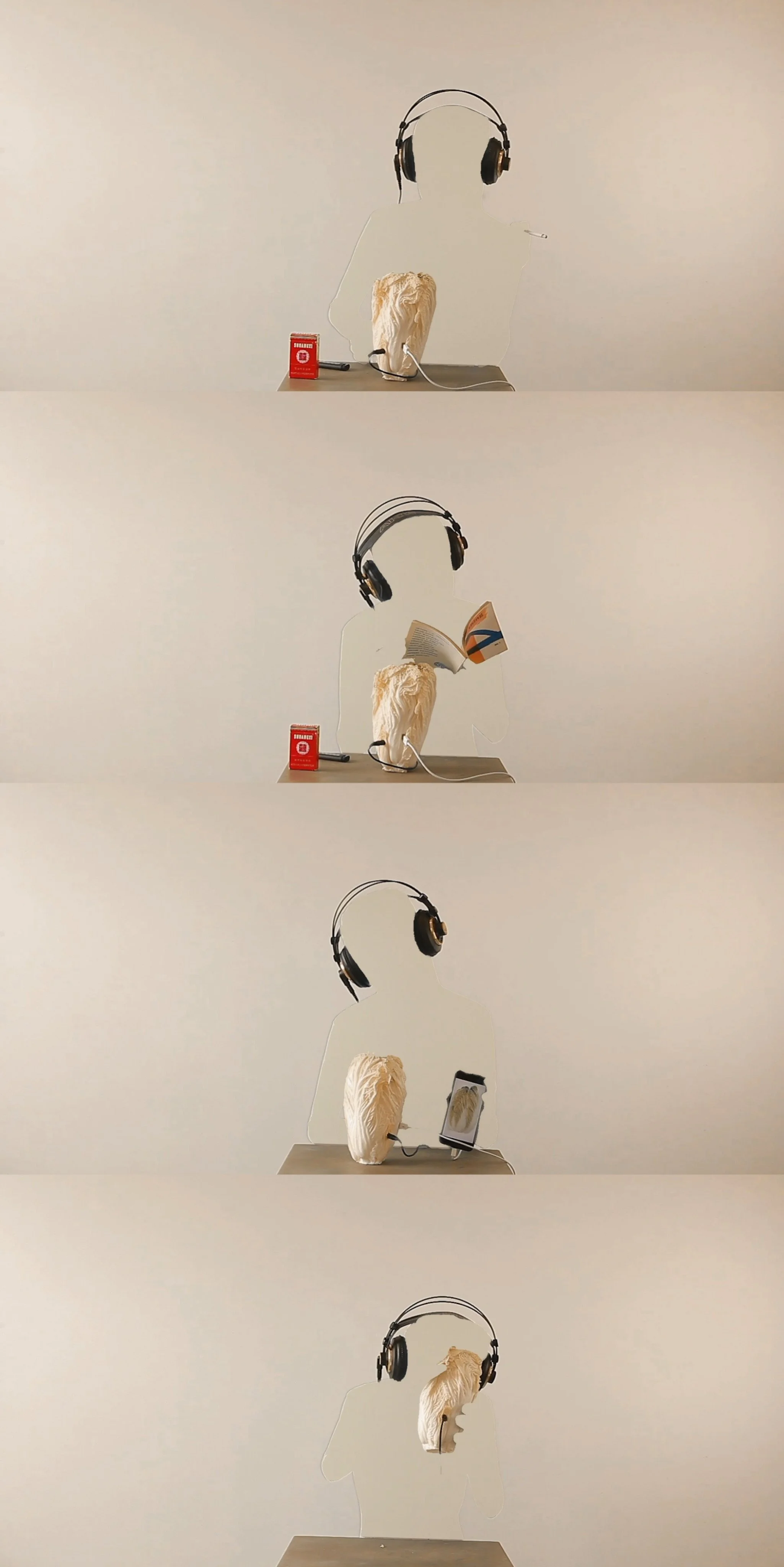

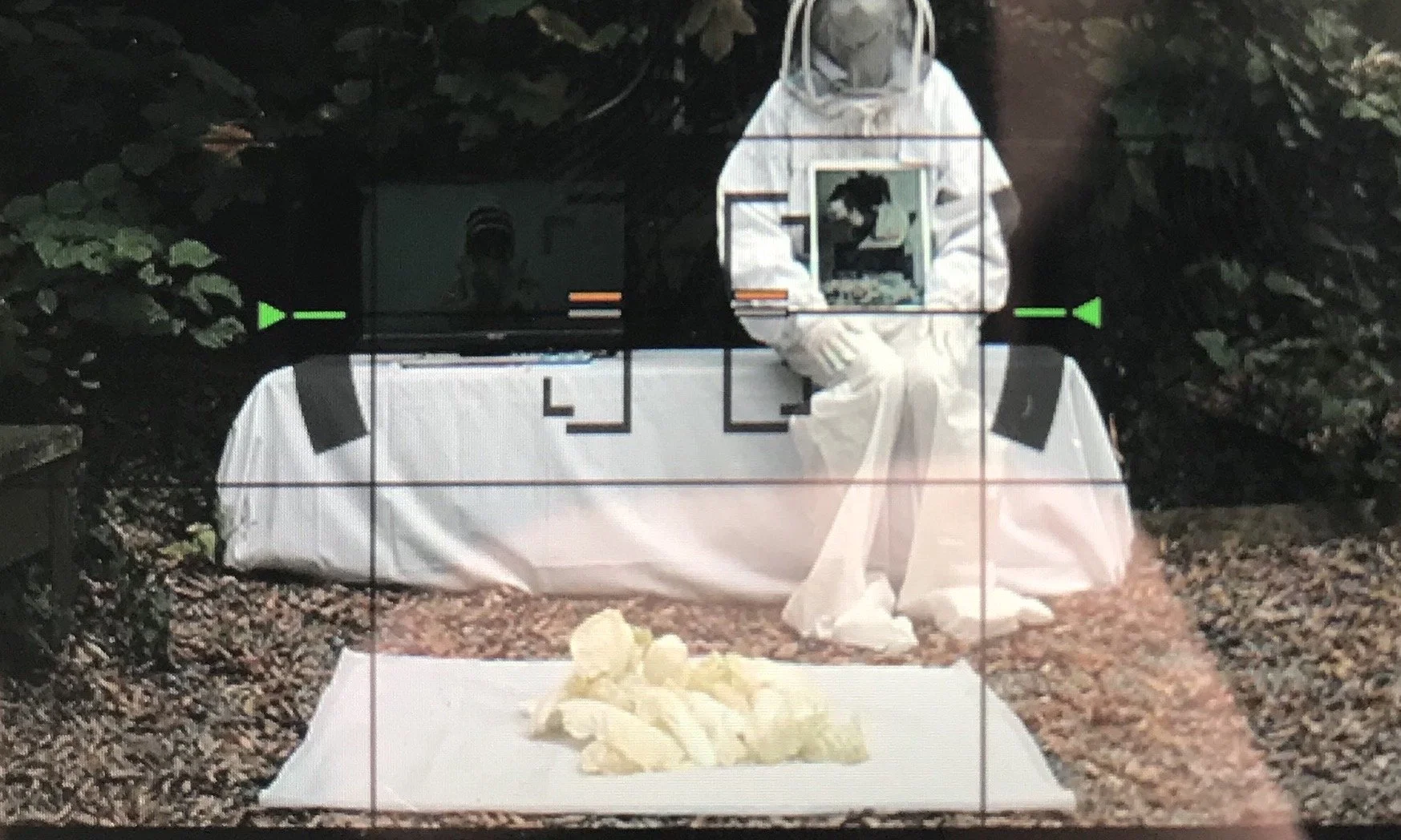

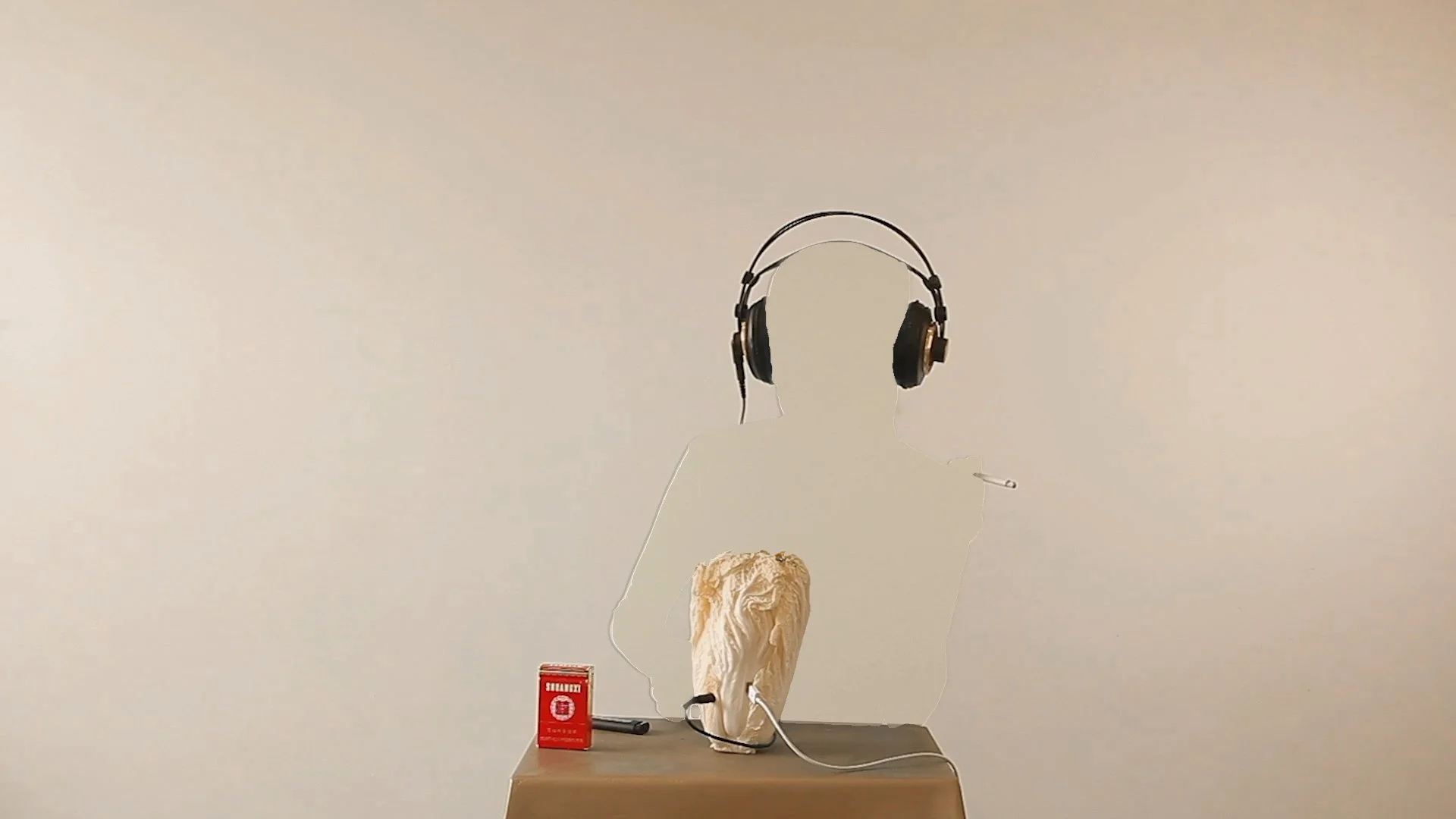

One of my favorite performance pieces is Sepπ, along with Napa Apparatus. These two works conceptually embody my ongoing exploration of asemic art. What makes them special to me is how they attempt to liberate the ontology of the world from anthropocentric narratives and reductive material fantasies.

In these projects, I activate sensory elements—such as sound and touch—as carriers of meaning through asemic writing, semiotics, and concrete poetry. My role as the interpreter is not that of an authoritative voice, but rather that of an agent participating in meaning-making alongside the material itself.

Whether or not matter possesses intrinsic agency, these acts of “composing” and “interpreting” allow materials to participate in the differential becoming of the world. These works don’t simply reflect reality; through feedback, interaction, and embodied presence, they generate new layers of understanding—constructing more complex, expanded forms of reality.

In what ways do you hope your work influences how people perceive language, nature, or the non-human?

My work does not simply represent language, nature, or the non-human; rather, it is an ongoing process of interpretation, deconstruction, and reconstruction. The subjects I engage with are understood as “existences” that are broken down into elemental units and reassembled into open-ended systems. This process itself is a poetic construction—a re-generation of what we call reality.

I hope that through interacting with my work, viewers become aware that our understanding of the world is never neutral. Every act of seeing, experiencing, and narrating is a way of participating in the construction of reality. The fragments of language, non-human agents, sounds, symbols, and rhythms within the work invite the audience into a “textual reciprocity”—where you, I, others, and the non-human entities embedded in the piece together produce the reality we know.

In this sense, each act of interpretation is not merely a search for meaning but a mediating action between cognition and text. Through this approach, I aim to prompt viewers to rethink their distance from language, their relationship with nature, and how the non-human actively participates in our experience of reality.

Are there any particular materials that consistently pull you back in, conceptually or physically?

Almost all of my works across various media involve napa cabbage, including those in digital media. As a way to contextualize my practice within the framework of material ecocriticism, I focus not merely on the organic, material qualities of cabbage, but more importantly on the roles these materials play in a posthuman, post-nature paradigm. My embodied aesthetics and visual politics dramatize and respond to recent shifts in communication and the humanities—particularly the evolving relations among humans, nonhumans, nature, and technology.

In particular, napa cabbage functions as a “diffraction apparatus” that helps to elucidate how concepts and objects are encoded and decoded within evolving patterns of difference.

Living in Brooklyn now, how has the environment or creative community influenced your more recent projects or performances?

In my experience, Brooklyn feels far more vivid and multilayered than broader New York City. Unlike Manhattan’s fast-paced and often overwhelming intensity, Brooklyn feels like having a more grounded, tactile environment—one where materiality, lived experience, and human-scale interaction are more palpable. This closely aligns with my interest in embodied aesthetics and relational systems, making Brooklyn not just a backdrop, but an active context for my practice.

What is a fun fact about you?

I've been eating napa cabbage every single day for six years—and I still do.

What else fills your time when you’re not creating art?

I love spending time learning new plants and working on my own plant projects. I also enjoy reading and writing poetry, exploring the world of natural wine, and window shopping for space-age furniture (even if it’s just for inspiration). Lately, I’ve been learning ikebana and experimenting with interior design and space arrangement.