Producing on the Faultlines: From Live Performance to XR

A Conversation with Wayne Ashley of FuturePerfect Studio

By Cansu Waldron

Wayne Ashley is a producer and entrepreneur with over two decades of experience shaping the XR ecosystem across virtual reality, mixed reality, video gaming, live performance, installation, and immersive design. As Founder and Executive Producer of FuturePerfect Studio, he has worked at the cutting edge of culture and technology, developing projects that bring together art and innovation.

Throughout his career, Wayne has collaborated with world-renowned artists, institutions, and corporations including BAM, NY Live Arts, William Kentridge, Iris Van Herpen, Nike, and Bell Labs. His roles have spanned curator, consultant, project manager, and cultural strategist, giving him a unique perspective on how immersive experiences can transform audiences and industries alike.

We asked Wayne about his creative process, inspirations, and vision for the future of XR.

City of Apparition

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

I originally trained as a dancer and theater artist, with a strong interest in experimental performance and alternative training systems—both Western and non-Western. My early practice was rooted in embodiment: not just in choreography and text-based theater, but in physical vocabularies shaped by distinct traditions, from contemporary dance to forms like Kathakali. I was drawn to the ways performance training encoded values—cultural, aesthetic, and political—into the body.

Me performing the role of Krishna in Trivandrum, Kerala, India (1973)

While completing graduate work in Performance Studies at NYU, I spent time in India studying ritual performance and traditional theater systems. That fieldwork, combined with my research into the aesthetics of everyday life, deepened my interest in how bodies move through—and are shaped by—social, architectural, and technological environments.

After graduate school, my career shifted. I moved to the Pacific Northwest and began working in digital imaging—first teaching software tools to photographers and designers, and then entering the broader world of media production and digital curation. It was here, almost sideways, that I began to explore how technology could reshape the conditions of performance, visual culture, and participation. How do we tell stories when the interface shifts? How does a digital system—whether a camera, the internet, a VR headset, or a game engine—become a creative partner? What are new distributed modes of curating and making art? What different viewing practices are emerging within these electronic networks? Those questions have remained central to my work ever since.

Over time, I’ve found that my impact lies not in identifying as an “artist” in the traditional sense, but in taking on the role of a catalyst—someone who initiates unexpected collaborations and builds the conditions for invention. That role has allowed me to construct encounters between people who might never otherwise share a language—aquatic acoustic engineers, choreographers, instrument designers, game developers, statisticians, even epilepsy doctors. My job is to shape the chemistry, to provoke and sustain productive collisions that lead to new forms and social encounters.

The future of art and performance—especially in the realms of extended reality, AI, and virtual production—is not about singular authorship. It’s about building ecosystems of imagination.

Can you tell us about FuturePerfect Studio, and how has the studio evolved since its founding?

FuturePerfect emerged out of a specific cultural moment—one marked by both opportunity and conflict. In 1999 and the early 2000s, I held senior roles at two major New York cultural institutions: BAM and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. I was tasked with integrating digital media and interdisciplinary practice into institutional programming—collaborating with Bell Labs and Lucent Technologies, leading cross-sector residencies, and curating projects that brought artists into conversation with scientists, engineers, and new technologies.

While these roles allowed me to work at the forefront of emerging practices, they also revealed how difficult it was—at the time—to shift institutional cultures fast enough to keep pace with the questions artists and technologists were beginning to ask. Digital tools were often siloed into marketing, education, or archival functions—but difficult to integrate into the creative process or public experience. After the dot-com bust, support for artist-driven experimentation sharply declined, as corporations and commercial interests moved in to define the digital landscape on their own terms. The once-vital energy around networked art—so visible in the net.art movement of the 1990s—was increasingly displaced by commercially-oriented design, branded content, and platform consolidation. Major institutions that had briefly explored new media withdrew or reabsorbed those initiatives into more conventional programs, and artists working in code, networks, or interactivity found themselves increasingly unsupported by the cultural infrastructure.

FuturePerfect was born in response to that decline—as an alternative structure: a space where speculative art-making, cross-disciplinary thinking, and technological risk didn’t need to be translated into legacy terms or flattened into utilitarian function.

FuturePerfect’s early projects made that structure palpable. In 2009, we launched with ZEE, a three-week installation by artist Kurt Hentschlager presented at 3-Legged Dog Art & Technology Center in New York. ZEE was a hallucinatory environment—dense fog, stroboscopic light, and low-frequency sound combined to erase spatial cues and trigger actual mandala-like hallucinations in the brain of each viewer for 20 minutes. The work wasn’t about visual spectacle; it was about sensory recalibration. We custom-built the enclosure and managed entry in small groups to preserve its intensity and maintain safety. It was an experiment in full-body perception—precisely the kind of risk-heavy, tech-centered experience that institutional settings could not contend with.

Zee (2009)

We followed with Shuffle (2011), a performance installation commissioned by FuturePerfect from Elevator Repair Service, statistician Mark Hansen, and artist Ben Rubin. Presented during the New York Public Library’s centennial, the piece was an early prototype of what we now call generative dramaturgy—a glimpse into how algorithmic systems might intervene in live performance. It used a custom database of canonical texts—The Great Gatsby, The Sun Also Rises, The Sound and the Fury—to generate new scripts in real time. Actors received their lines via iPod Touch devices embedded in paperback books, improvising their movements and delivery based on software prompts. The audience wandered among them in a working periodical room.

Shuffle (2011) as part of the New York Public Library Centennial

In 2015, we co-developed, produced, and toured Aquasonic, an underwater concert initiated by the Danish ensemble Between Music. It featured custom-built submerged instruments and vocals performed entirely beneath the water. It was an audacious idea—part sonic engineering feat, part otherworldly opera. FuturePerfect brought together aquatic acoustic specialists (Preston Wilson), tank fabricators, instrument designers (Andy Cavatorta), and inventors to turn an improbable vision into an international touring success. The piece continues to tour globally and remains a touchstone for how FuturePerfect bridges speculative performance with highly technical production.

Aquasonic (2015)

Aquasonic (2015)

These early works didn’t just combine disciplines—they tested what kinds of environments were necessary to sustain artistic invention when computation, embodiment, and sensory transformation were central to the project.

In more recent years, FuturePerfect has expanded into virtual production, real-time rendering, and extended reality—tools that have reshaped not only how we create, but how we collaborate. The COVID-19 pandemic, like for many studios, marked a critical turning point. Our physical projects were halted, and we were forced to ask: do we shut down or radically adapt?

Inspired by the technical knowledge and creative instincts of our longtime Technical Director, Xander Seren, we chose the latter. We reconnected with earlier work we had done in platforms like Second Life, and our long-standing curiosity about game engines as creative environments. Years before it became fashionable, we had supported artists, architects, and filmmakers who were pushing the boundaries of popular video games and virtual worlds—repurposing their code, physics, and glitches to produce machinima, performance, and installation. Those conversations gave us a foundation to re-enter digital space on our own terms.

Over the past three years, we’ve built two original VR-based works, a video game, and a mixed reality experience.

Starve the Algorithm, developed in collaboration with South African artist William Kentridge, marked his first foray into the immersive space of the metaverse. We designed a series of visual and navigational experiments—inhabited by fragments of Kentridge’s ideas, imagery, and investigations of history. Wearing a VR headset, viewers moved through an architecture of interlocking rooms: the artist’s studio, a kinetic theater, a hall of curiosity cabinets, and a crescendo of megaphones. We aimed to carve out a space that favored the untranslatable and the unpredictable—challenging the supposed infallibility of algorithmic systems.

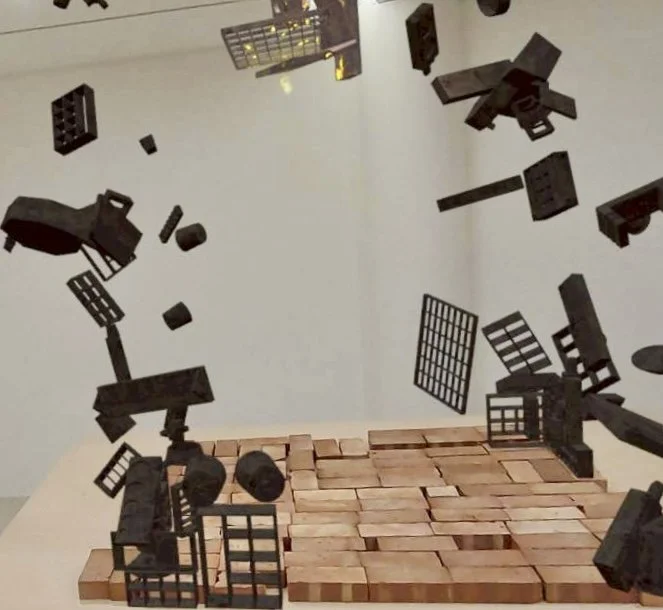

Cardboard Maquette by William Kentridge for our VR work Starve the Algorithm (2021)

Starve the Algorithm Installation and VR, Taiwan Creative Content Festival (2021)

Studio Visit, a surreal, interactive environment created with sculptor and playwright Will Ryman in Unreal Engine, invited audiences into a spatial rendering of the artist’s imagination. Using motion capture and 3D scanning technologies, we reconstructed Ryman’s studio—now reanimated by his sculptures, which appeared to come alive in strange, theatrical ways. The result was a dreamlike encounter with creative process, distortion, and materiality.

Studio Visit (2021)

Studio Visit (2021)

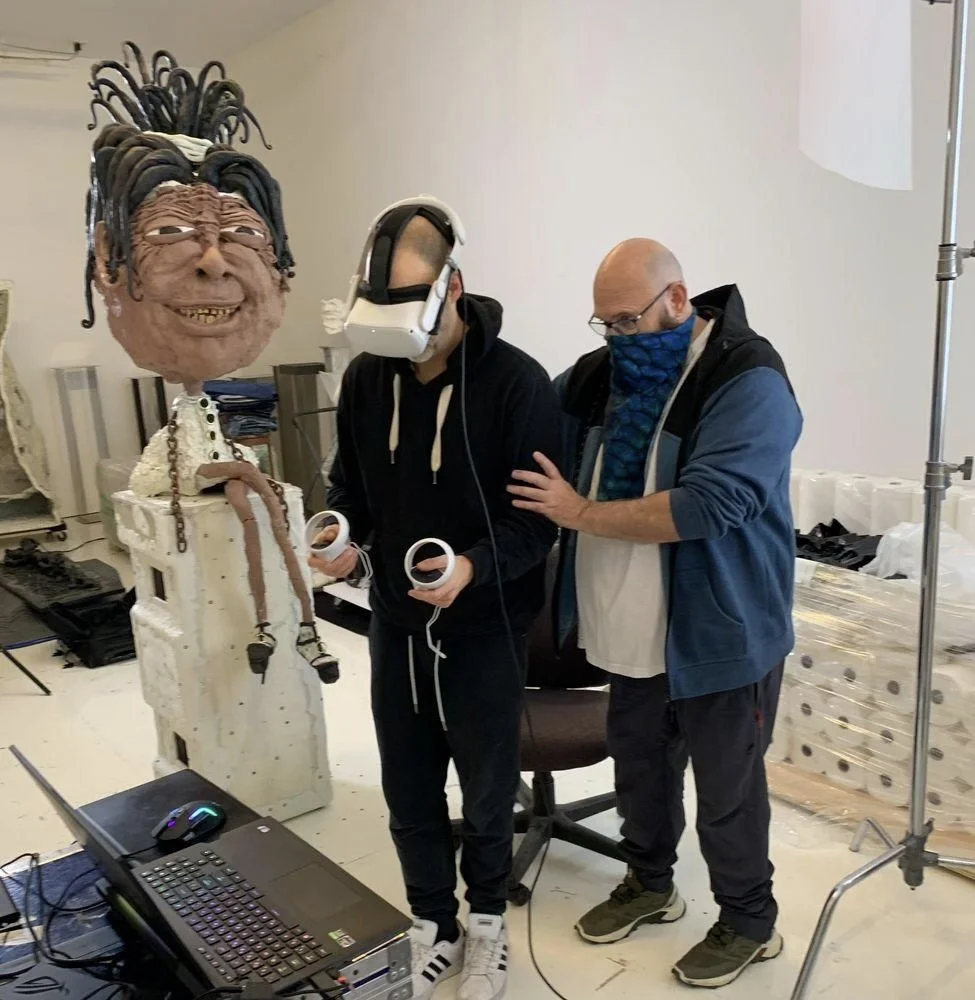

We’ve just completed the introduction to City of Apparition, a mixed reality experience with VR headsets exploring the emotional and spatial dislocations caused by loss of home. Created together with Taiwanese artist Lin Shu-Kai, the work blends physical and digital worlds—allowing viewers to interact with fragments of a disappearing city, a childhood home, and the imagined structures that emerge in their place.

The project draws on Lin’s personal experience of urban demolition in Taiwan. When part of his family’s home was forcefully torn down, the rupture—both emotional and material—sparked a deep inquiry into the instability of cities and the volatile conditions shaping the world today. Based on Lin’s drawings, sculptures, and installations—I directed his narrative, together with our development partner Agile Lens, through an immersive and multi-sensory journey. We presented a 7-minute demo of the work at The Hudson Eye Festival, and recently at a joint exhibition with Lin, called Unhoming Reworlding, at the Der-Horng Gallery in Taiwan. The work was reviewed by the digital curator and writer Cansu Waldron.

City of Apparition Der Horng Gallery (2025)

City of Apparition, FuturePerfect Studio and Lin Shu-Kai (2025)

In the last ten years, some things have definitely changed since FuturePerfect began. Today, extended reality, AI, and virtual production are slowly gaining legitimacy within museums, educational institutions, and creative research contexts.

What are some of the most challenging and rewarding aspects of collaborating with external clients, from artists to governments, while maintaining the studio’s creative vision?

One of the most persistent challenges in our work is that the role of producer—especially in a hybrid, exploratory context like ours—is often misunderstood. People rightly tend to associate producers exclusively with logistics, budgeting, scheduling, or fundraising. And yes, we do all of that. However, in our studio producing is not a secondary function—it’s a creative practice. We don’t simply realize a vision; we help shape it. We interrogate ideas, translate between artistic intent and technical constraint, and mediate between institutional requirements and speculative possibilities. That act of translation is where much of our creativity lives.

We often find ourselves in the in-between: across forms, disciplines, industries, and scales. That in-betweenness is deliberate—it allows us to work fluidly, to hybridize. But it also confuses people–not always good for business. I once had an unforgettable argument with an artist who shouted and chastised me for not making an either/or choice: were we presenters, producers, artists, curators, or some kind of service organization? I take full responsibility for that confusion. But after 17 years of continuous production, I’ve come to see that occupying the blur is not a failure of definition—it’s a position of creative leverage. I want to stay there.

Working as an Executive Producer and collaborator in the independent performance sector—both nationally and internationally—means navigating some misunderstandings about how projects actually come into being. There’s sometimes a blindness of how money is raised, how collaborators are assembled, or how infrastructure varies by geography. In the U.S., public funding for artists and studios like ours is extremely limited. We don’t have access to the sustained government support that many European organizations, for example, benefit from. Every project we produce is an act of alignment, resourcefulness, and risk. Because we often operate at the margins of established production systems, collaborations can arrive with insufficient funding, making sustainability and growth a persistent challenge. And yet—we take them on, because they align with our vision and push us forward.

Still, the rewards for working with external clients can be profound. They bring us new content, expand our aesthetic vocabulary, make us work with different skill sets and expertise, and bring different kinds of questions, assumptions, and problems to solve. It’s like going on an excavation each year, and making new discoveries. And often they bring a different network of followers and audiences. And of course financially it’s been crucial.

Supporting—and expanding—our studio requires holding two forces in tension: our creative aspirations and the economic ecosystems that make them viable. Sometimes we have failed. But that tension isn’t a flaw in our work—it is the work.

Your collaboration with Jonah Bokaer Choreography and the Jonah Bokaer Arts Foundation sounds like a fascinating leap — how did it begin, and what drew you to work specifically with them on AI and performance?

The collaboration is built on a long-standing relationship. Jonah and I have known each other for nearly two decades. He had hired me as the founding Executive Director of CPR - Center for Performance Research in Brooklyn, and we've stayed in conversation ever since—circling one another’s practices, methodologies, and institutional experiments.

Jonah’s background in the Merce Cunningham and Robert Wilson legacies—particularly his interest in scores, chance operations, and virtual processes—made this a natural convergence. His practice has long embraced systems thinking and computation, and those processes resonate with how FuturePerfect approaches emerging technologies like machine learning, and our current focus in XR. So in many ways, this collaboration isn’t a “leap” so much as a return to a shared interest.

Together, we’re developing Bad, Bad AI: A Phased Initiative for Rethinking Intelligence and Embodiment Across Contemporary Art & Performance. This is a modular initiative that reframes artificial intelligence not as a neutral tool, but as a cultural and choreographic condition. We’re at the very beginning stages. The project will eventually include a public speaking series (Performing the Machine), an artist residency, a research convening (Performing Intelligence), and a production pipeline for new work. These aren’t siloed programs—they’re designed to cross-pollinate: we’re building an ecosystem where visual artists, directors, creative technologists, choreographers, and scholars can interrogate how intelligence is embodied, simulated, or staged.

What excites me about this collaboration is not simply the convergence of art and AI. It’s the fact that we’re creating new infrastructures for experimentation. We’re not just making work—we’re designing conditions, vocabularies, and relationships that can sustain a different kind of cultural production. We’re also asking who gets to shape the narratives around AI? This partnership is still unfolding, but it’s already revealing something vital: that performance isn’t just a place to use technology. It’s a space to challenge its assumptions, rewrite its metaphors, and choreograph its futures.

You're exploring “dramaturgies of the synthetic” — can you unpack what that means for you in the work you make?

For us, “dramaturgies of the synthetic” means rethinking the core principles of performance in an age shaped by simulation, real-time computation, and artificial systems. Traditionally, dramaturgy is understood as the structure and logic behind a performance—the arc of narrative, the rhythm of scenes, the development of character and intention. It’s deeply human-centered: a craft of meaning-making grounded in psychology, language, history, and physical presence.

But what happens when the structures shaping performance are not only human, but also machinic?

We’re not just using digital tools to stage or support live events. We’re asking: what if the system itself—an AI model, a generative script, a game engine—becomes a co-author of the event? What if motion capture data, lidar scans, photogrammetry, or algorithmic behaviors are not just effects or add-ons, but dramaturgical forces in their own right?

This exploration runs through many of our works. In Starve the Algorithm, our VR collaboration with William Kentridge, we built a spatial dramaturgy that rejected linear storytelling in favor of fragment and drift. The logic of the piece wasn’t governed by plot, but by how viewers navigated the simulated and software generated debris of image, sound, and gesture—creating their own interpretive structure within a world haunted by Kentridge’s ideas, puppets, lectures,and maquettes, re-configured for our immersive environment.

A formative example for us is Shuffle (2011). A custom database recombined canonical American novels to produce real-time scripts, which were delivered to actors via handheld devices. Their speech, movement, and spatial cues were all driven by the system—making the software not just a tool, but the dramaturg. In Shuffle, the logic of the event didn’t originate from a playwright or director, but from the dynamic interplay of data, code, and embodied response.

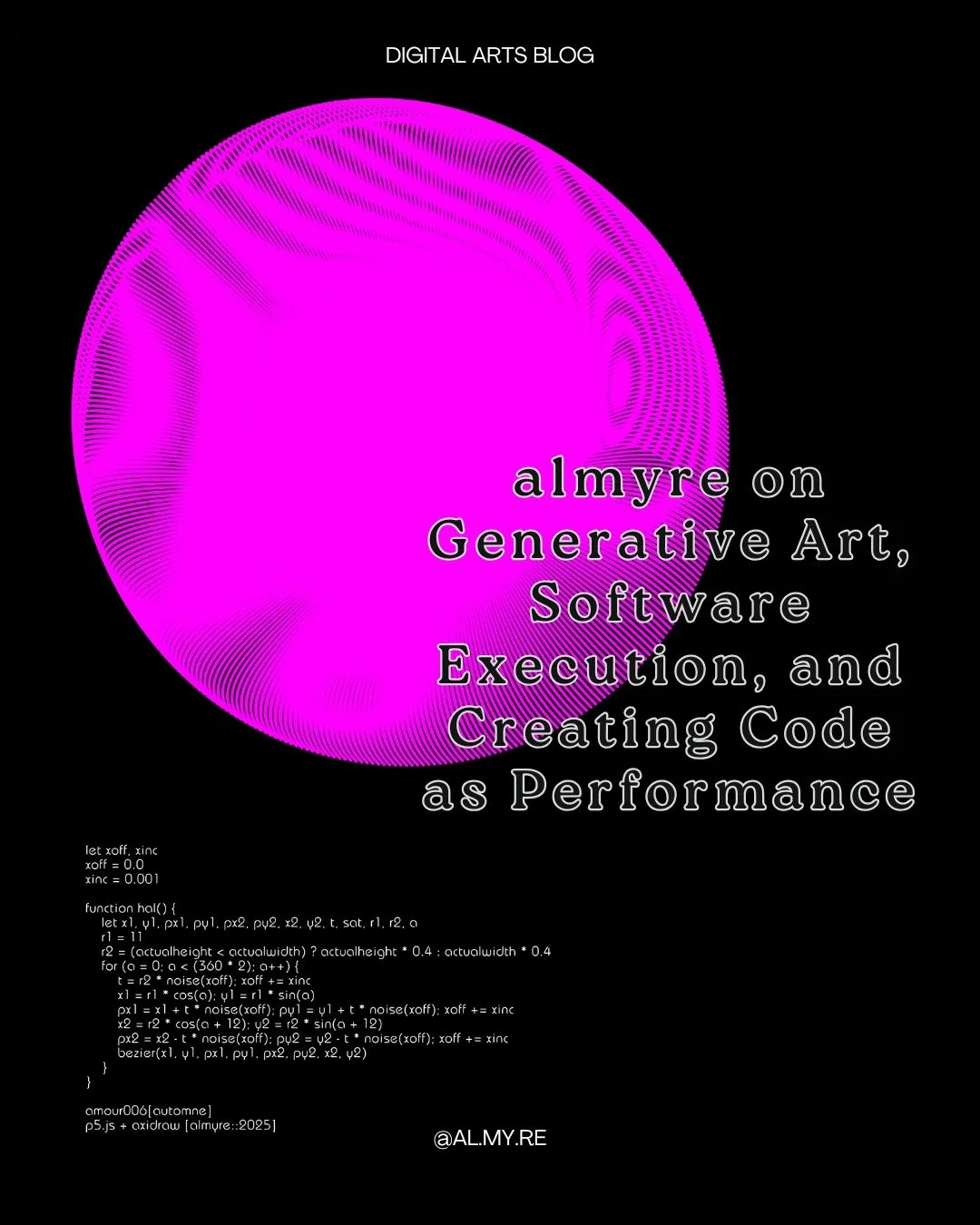

And with Void Climber, our first original video game, we brought these ideas into the context of play. The game’s procedural platforming mechanics are framed not as a puzzle or narrative, but as a performative loop—a dynamic field through which the player’s body learns rhythm, failure, timing, and tension. There is no authored story. The dramaturgy arises from the relationship between the player and the system—one fall at a time.

Void Climber (2025)

Void Climber (2025)

Dramaturgies of the synthetic don't describe a single technique. They describe a field of inquiry—into presence without bodies, into time without narrative, into agency without consciousness. I’ve debated with many colleagues who argue that such processes will eliminate creativity, and do away with liveness. That’s not what I see, or what I desire. I want to expand the field of performance and redefine liveness to include digital doubles, simulated spaces, generative language, and algorithmic decision-making.

How do you see the future of extended reality evolving, both in terms of technology and its impact on art and culture?

We’re entering a phase where XR will no longer be a novelty—it will become part of the infrastructure of how we create, share, and experience work. As devices become lighter, more interoperable, and increasingly spatially aware, XR will contribute to more and more cultural experiences—from exhibition design to rehearsal processes and scenographic thinking. It won’t replace other forms of performance, but it will offer new layers—ways to fold memory, space, and sensation into live and mediated experience.

What excites me most isn’t the technical fidelity—it’s the conceptual shift. XR can collapse space, simulate presence, and reconfigure time—reshaping how artists and audiences relate to each other and to the work itself. Just as importantly, it enables artists to circulate their work globally without being physically present. That’s a financial benefit! It offers audiences, especially those without the means to travel, or who feel uncomfortable in the social spaces of “art,” access to experiences they might otherwise never encounter.

What’s a fun fact about you?

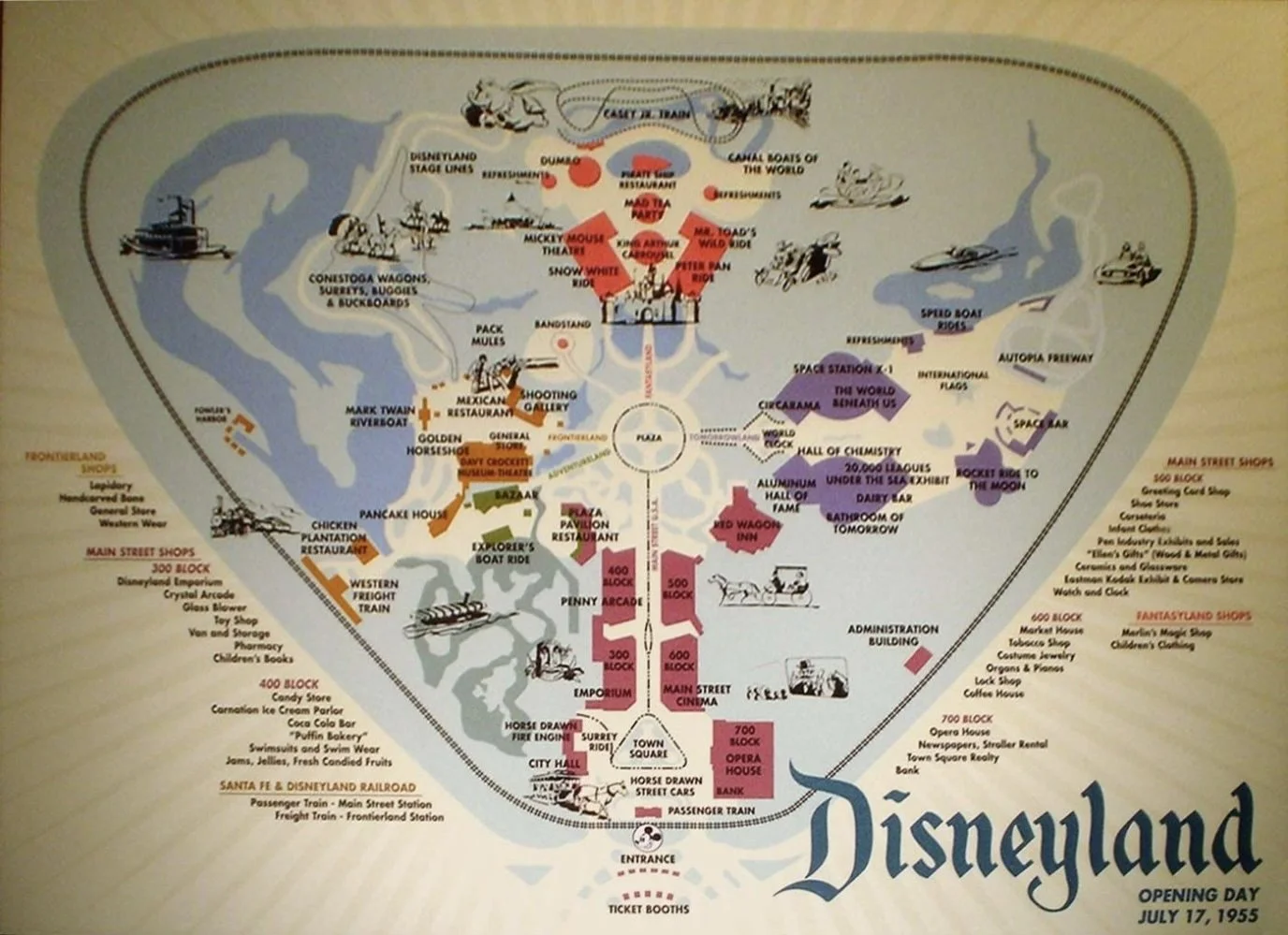

During college, I worked as a janitor at Disneyland in Anaheim! I mopped the bathrooms in Tomorrowland, scraped gum off the streets of Main Street, and vacuumed the animatronic interiors of Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion. It sounds mundane, but it left a mark. I had grown up in Southern California during the 1950s and 60s, and visiting Disneyland at least once a year was normal. At times, I’ve tried to hide that history from my biography but its effects keep popping up, like persistent ghosts–robotics, 360-degree cinema, animatronic choreography, telematics, immersive multisensory-themed rides, and speculative futures built from plastic, light, and industrial design.

As much as my own training and practice had been relentlessly physical, I have always been captivated by environments where live humans weren’t always the center of the work. That fascination still drives me.

Disneyland Map (1955)