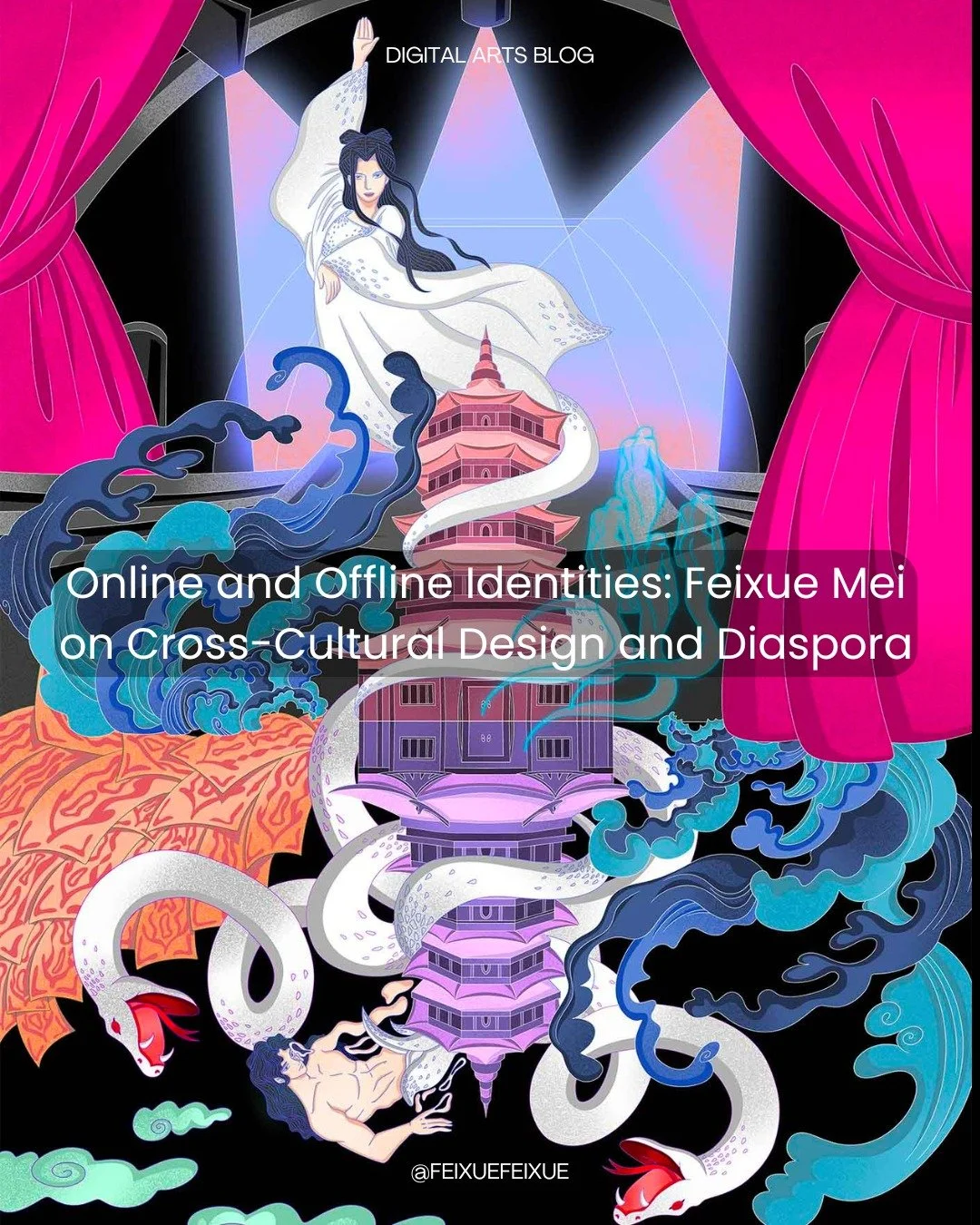

A Visual Haiku: Wenwen Zhu’s Quiet Worlds of Imperfect Grace

By Cansu Waldron

Wenwen Zhu is a Chicago-based animator and illustrator whose work lives in the space between surrealism and wabi-sabi — where imperfection, stillness, and mystery quietly coexist. Moving between 3D animation and drawing, she builds poetic worlds that invite viewers to linger and feel rather than decode. Her images often explore the subtle ties between people, society, and nature, revealing emotion through restraint and atmosphere instead of narrative clarity. Each piece feels like a visual haiku — spare, ambiguous, yet deeply resonant.

Wenwen began her journey in illustration at the School of Visual Arts, where she developed a love for quiet, self-contained images. Later, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she turned to 3D animation and sound, extending her visual storytelling into time and movement. Her approach blends intuition with craft, surrealism with wabi-sabi, and stillness with transformation. The result is work that doesn’t dictate meaning but opens space for contemplation — an art of subtle gestures and lingering moods.

We asked Wenwen about her creative process, inspirations, and how she finds balance between motion and stillness in her work.

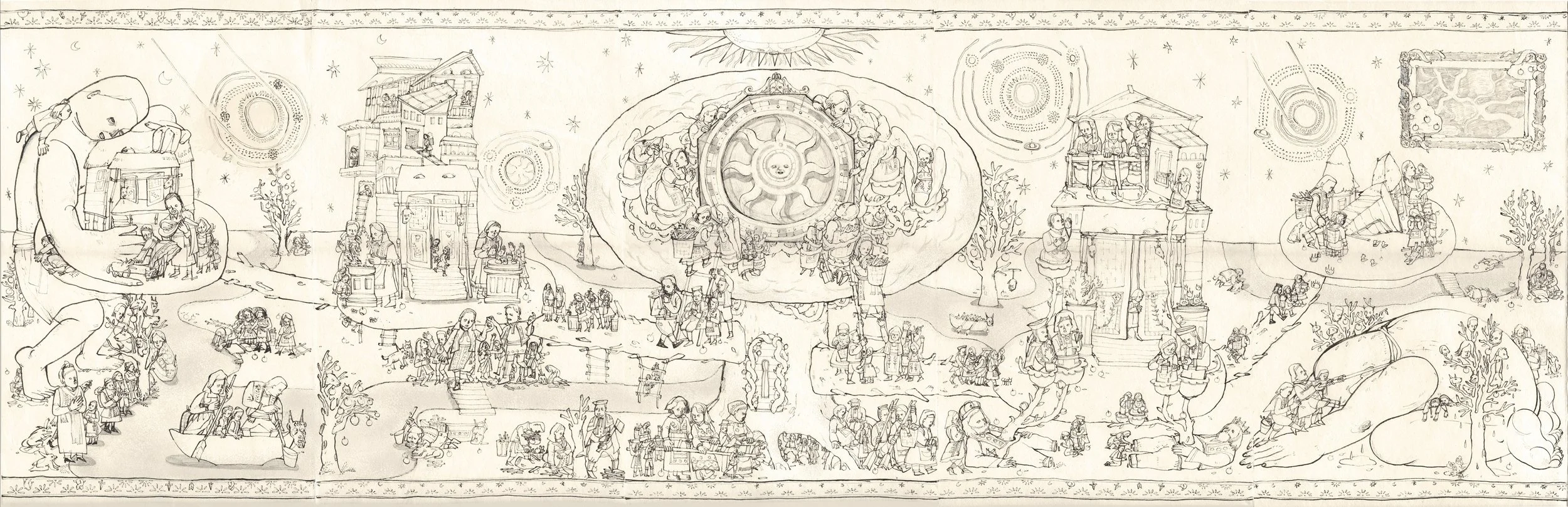

A Villiage Has Secrets

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

I began in illustration at the School of Visual Arts, where I fell in love with quiet, self-contained images. Later, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I studied 3D animation and sound because I wanted to extend that narrative impulse from the still frame into time. The goal wasn’t to abandon the still image, but to balance its compositional clarity with the richer, temporal storytelling that movement and audio allow. Learning animation, compositing, and basic sound design gave me a toolkit to let a drawing breathe — pace, rhythm, and atmosphere — so stepping into “digital artist” felt natural: it’s simply the place where my illustration sensibility meets motion and sound.

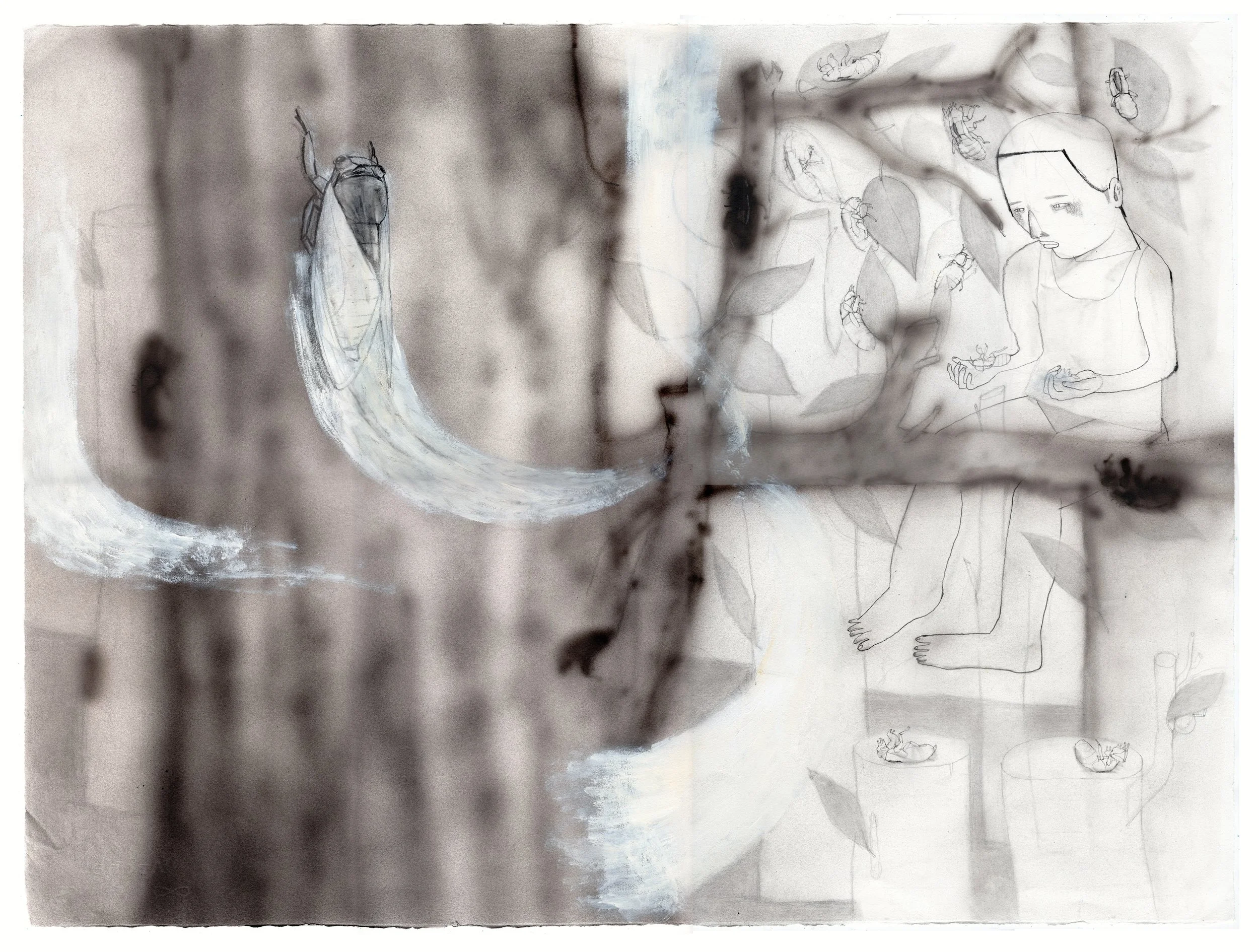

Beneath the Truth

Immortality

You mention blending surrealism with wabi-sabi philosophy. How did those two worlds come together in your artistic voice?

They meet in a simple principle I follow: “show, don’t tell.” Surrealism gives me permission to build image-based logic—symbols, unlikely juxtapositions, dream transitions—without over-explaining. Wabi-sabi, with its embrace of incompleteness and timeworn beauty, keeps the work open and breathable. Together they create space for viewers to project meaning: the piece poses a question rather than delivering an answer. Many images ask things I can’t resolve myself, and that’s the point—the ambiguity is not evasive, it’s invitational. Like a dream, it’s indistinct yet suggestive enough to move you.

Immortality

Wabi-sabi embraces imperfection — can you share an example of how an “imperfection” in your work became something essential?

I often keep negative space, partial coloring, or visible seams between hand-drawn textures and 3D renders. In one sequence, I left an area intentionally under-painted and allowed slight jitter in the linework; instead of feeling unfinished, it became the image’s breath—room for the eye to rest and for the viewer to “complete” the scene. The same applies to gentle render noise or a camera drift that isn’t mathematically perfect. When an artwork tells too much, it can feel like a forced confession. Imperfection invites curiosity and empathy; the audience adds the final piece of the puzzle, so the film becomes whole only through their participation.

Praying Under the God Tree

What first drew you toward animation as a medium for quiet, poetic storytelling?

Experimental music. While drawing, I realized paper fixed the moment but muted the timing of emotion. Music taught me that feeling is shaped by duration, silence, and return. Animation lets me compose time the way a score does—setting tempo, holding a pause, letting an image arrive late. Adding field recordings and subtle sound design expanded the sensory range, turning still imagery into a lived atmosphere. For the kind of gentle, contemplative stories I pursue, animation is ideal: it keeps the intimacy of illustration while giving me control over breath, rhythm, and the soft afterglow of a scene.

The Truth of Compromise

Atmosphere is such a strong part of your work — what visual or sonic elements help you build that sense of immersion?

Atmosphere, for me, begins with a “hand-scroll” way of seeing. Visually, I build wide, lateral compositions where a single frame functions like a slow scroll—many small actions unfolding at once. Characters are busy with their own micro-tasks; nothing begs for attention, so the viewer chooses where to look and can settle into a focused, self-paced gaze. I stagger rhythms across foreground/midground/background, let motion drift rather than cut, and use soft blend and shallow breathing in the depth of field so the scene-to-scene feels seamless and continuous.

Tuned to Please

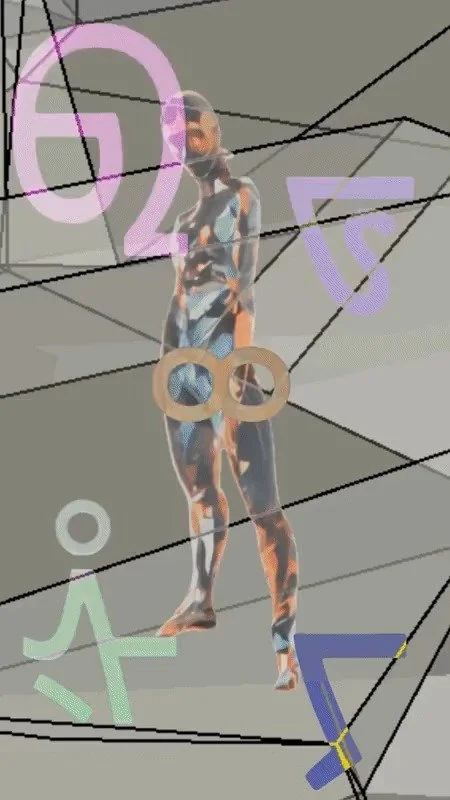

What new directions are you curious to explore next?

I’m moving deeper into a 2D–3D hybrid language. My current films already carry an illustration sensibility inside 3D environments, but I’m excited to try Blender’s Grease Pencil to draw directly in three-dimensional space. The aim isn’t a tech demo—it’s to keep the intimacy of drawing while expanding the spatial and temporal possibilities of animation.

Early Spring

Is there a story, image, or memory you’ve been carrying with you that you hope to transform into a future project?

Yes—there’s a moment I keep returning to: the brief minutes after a downpour when the world turns blindingly bright. The ground is still wet, air heavy, and yet everything gleams as if too clean to be true. That emotional switch—from weight to brightness, reflection to interruption— feels both euphoric and unreliable. I’m developing a project called After Rainlight, a non-narrative study of this “wet radiance.” I plan to weave 3D environments with hand-drawn textures and ambient field recordings, letting images hover between states—wet/dry, real/constructed. It’s less about explaining a story than holding that rupture long enough for viewers to feel it.

We Don't Belong Here

The Moment the Cicadas Cry