A Pause Between Worlds: The Metaphoric Art of Yueming Li

By Cansu Waldron

Yueming Li is a visual artist whose work explores how images can tell stories and reveal the inner world through metaphor and symbolism. Drawing from everyday life, she creates visual narratives that invite viewers to pause, feel, and reflect. Having lived across different countries, Yueming sees art as a universal language — one that transcends words and connects emotions across cultures. Her works often feel meditative, guiding viewers into quiet, contemplative spaces where familiar moments take on a timeless, poetic quality.

Her illustrations have been internationally recognized by the Three x Three International Illustration Awards, Applied Arts Illustration Awards, Japan Illustrators’ Association Illustration Awards, London International Creative Competition, and Guangzhou Illustration Art Festival, among others. Whether inspired by a mysterious wall from her school days or the subtle awakenings of feminine consciousness, Yueming’s art transforms memory and emotion into visual metaphors that spark empathy and conversation.

We asked Yueming about her creative process, inspirations, and the stories behind her art.

Bury Me

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

Before my junior year of high school, my practice focused on traditional media, such as oil paint, acrylic, gouache, pencil and charcoal. The turning point came one day when I went to a photo studio for my visa photo. While waiting, I noticed an employee using a mouse to paint in Photoshop. That was the first time I had ever seen someone paint digitally in real life. Before then, my only experience with digital creation was making simple Flash animations.

But painting with a mouse was challenging for me. After some research, I bought the most affordable drawing tablet available and started experimenting on my own. I decided to continue in this direction because the digital medium effectively freed me from the constraints of traditional media, especially regarding scale and the use of highly saturated colors. At the same time, the technical foundation I had developed through years of training in traditional media greatly supported my digital exploration. From there, I began a process of self-learning digital painting while gradually advancing my artistic journey.

Flowing Moonlight

Everyday life seems central to your inspiration. How do you recognize when an ordinary moment has the potential to become art?

When I find myself repeatedly thinking about something while zoning out or before falling asleep, I know there is something within it that I want to express or share through my work. For example, my work “The ‘Library’,” which was selected for the 2022 China Illustration Art Yearbook, was inspired by an unusual wall in my middle school building many years ago. On my school’s floor plan, there appeared to be a huge space behind that wall, but in reality, we could not find any actual doors to enter. I always remember that afternoon when my friends and I pressed against the wall and knocked on it to hear the echoes. Even after all these years, I kept imagining the space behind that wall, which led me to create this piece with the concept of contradictory space.

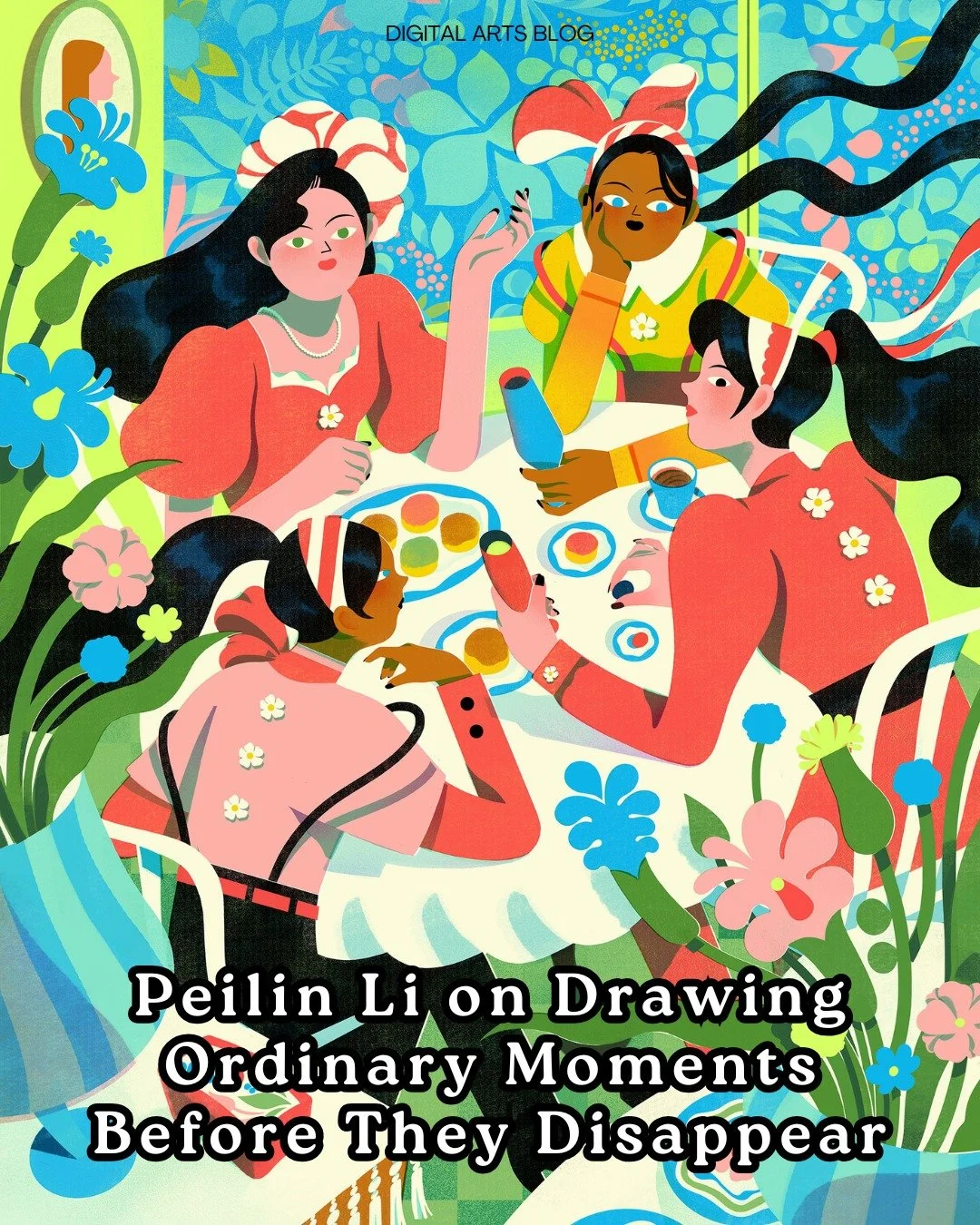

Sometimes, inspiration does not come from a single event, but from a combination of events and emotions that prompt my creation. A case in point is my work “Gazing,” which won the silver medal in the 2024 Japan Illustrations’ Association Illustration Awards. The inspiration for this work grew from the realization that, in the process of my feminine consciousness awakening, the gaze, judgment, and embellished frames entwined in my memories had long become traumas. Such gazes were disguised with positive expressions like “appreciation” and “admiration,” while as an independent individual, my thoughts, feelings, and will were ignored and dismissed.

Since I primarily work alone at home, I pay particular attention to my gatherings, communications, and interaction with family, friends, and strangers. Receiving information input from the outside world is important for me. I remember moments that bring an emotional reaction in me. These emotional shifts are never isolated, and they affect others, and thus become the crucial thread in my work that evoke resonance in the viewers.

Flying Birds

You often use metaphors and symbolism. Do these come intuitively, or do you consciously build them into your work?

Initially, the use of metaphors and symbols was intuitive and unintentional. However, as my understanding of visual content and expression deepened, I began to actively train myself to utilize them more effectively in my pieces. Many of the emotions I want to convey, the atmospheres I aim to create, and the ideas I want to express are quite abstract. Therefore, during the brainstorming phase, I try to find concrete representations for these abstract concepts through associative thinking.

For example, in my work “MaMa,” which also won the silver medal in the 2024 Japan Illustrations’ Association Illustration Awards, I utilized symbols such as the uterus, entwined snakes, a thread spool, the infinity symbol, and myself holding my mother’s finger. Through these symbols, I discussed, explored, and visualized the complex relationship with my mother, which also reflects the social context in which Chinese women in my generation are raised: a blend of conservative and progressive ideas. In this social backdrop, many mother-daughter relationships are marked by a mixture of love and pain.

Sometimes, my choice of symbols and metaphors is more straightforward. In “The Eternal Moon,” another piece selected for the China Illustration Art Yearbook, I rendered the shape of the moon to resemble an eyeball, visually interpreting the moon as a silent observer as described in a thousand-year-old poem: “People today do not see the moon of ancient times; yet the present-day moon once shone upon the ancients. Whether of the past or present, people are like flowing water; together they look upon the same moon.”

For me, using metaphors and symbols is similar to capturing an initial spark of inspiration during the sketching phase, which is intuitive. However, just as a rough sketch needs details to become a finalized work, the effective use of these elements requires conscious management and design.

Gazing

Having lived across different countries, how has this movement shaped the way you think about visual language?

I was born and raised in China, where I began following my mentor and learning to draw and paint at a very young age, starting with traditional Chinese brush painting. To this day, the concepts of “artistic conception” and compositional approaches from Chinese aesthetics continue to influence me deeply. Even when I later spent more time on techniques of European realistic painting, I still believed that the focus of visual language is not the perfect reproduction of a real-life object on canvas, but rather the conveyance of content through scene, lines, and atmosphere.

I then lived and studied in the United States for seven years. During this period, my work tended toward highly finished, narrative expressions. Although I began experimenting with the use of symbols and metaphors, it was still in an exploratory phase. I viewed a vast amount of editorial and book illustrations, leading me to believe that visual language should be primarily informative.

Later, I moved to Sweden. The long winters offered me extensive time for solitude, and my exploration shifted from outward to inward. I became more focused on what I, as an individual, wanted to express. It was then that I began to understand that a crucial part of visual language is self-expression. I realized that since I left my home country, I was in an “in-between” state. When reviewing my past experiences, I found myself occupying both the subject and the object positions, and I am both observing and being observed. My piece “Bury Me” is an example of the combination of this development in my understanding of visual language. Through bright, vibrant imagery and atmosphere, I attempt to convey my thoughts on death and explore the relationship between the momentary and the eternal.

Now, having moved back to the United States, I am engaging with people from more diverse backgrounds and professions. I look forward to seeking out further cultural differences and commonalities and continuing to practice the universality of visual language in my work.

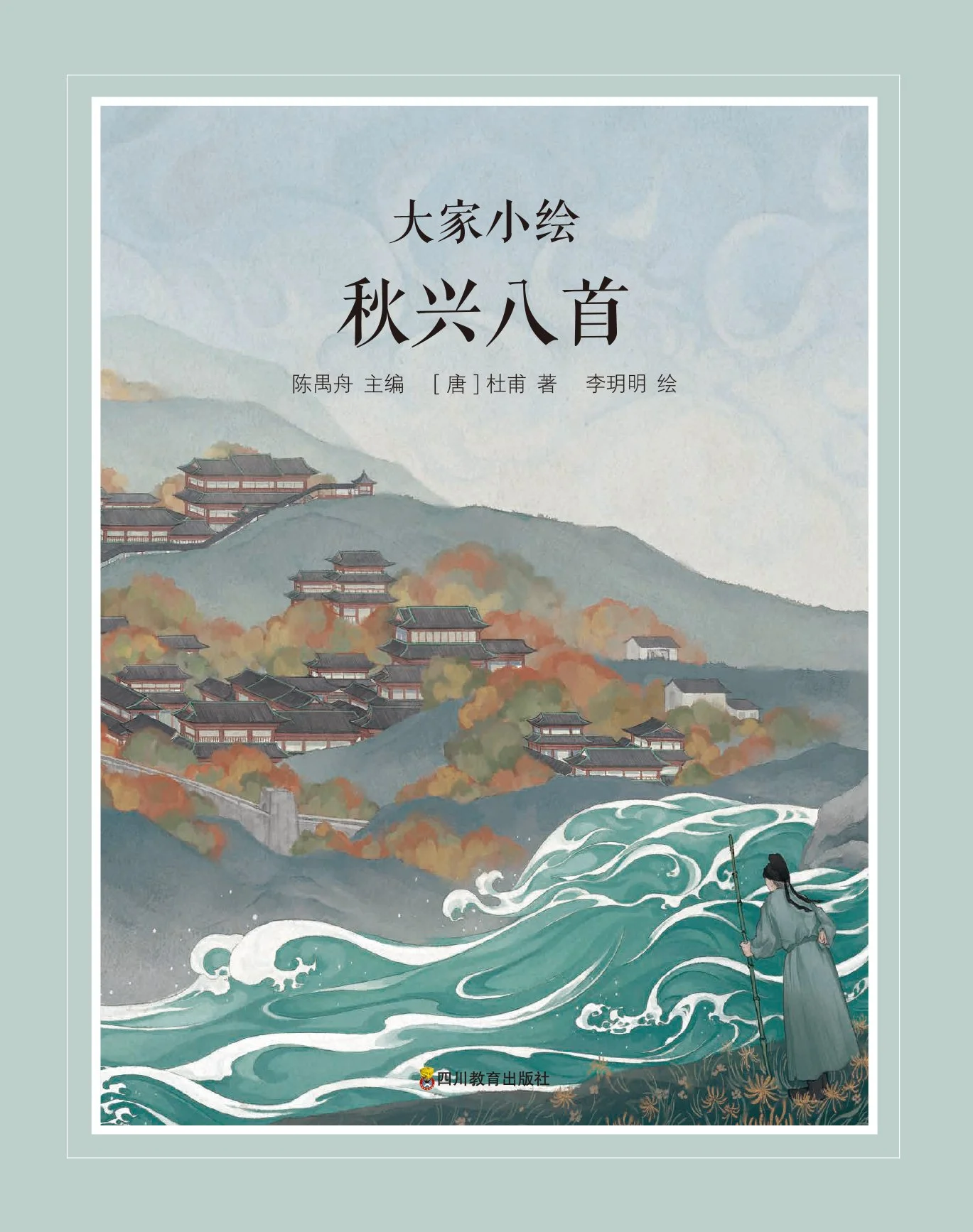

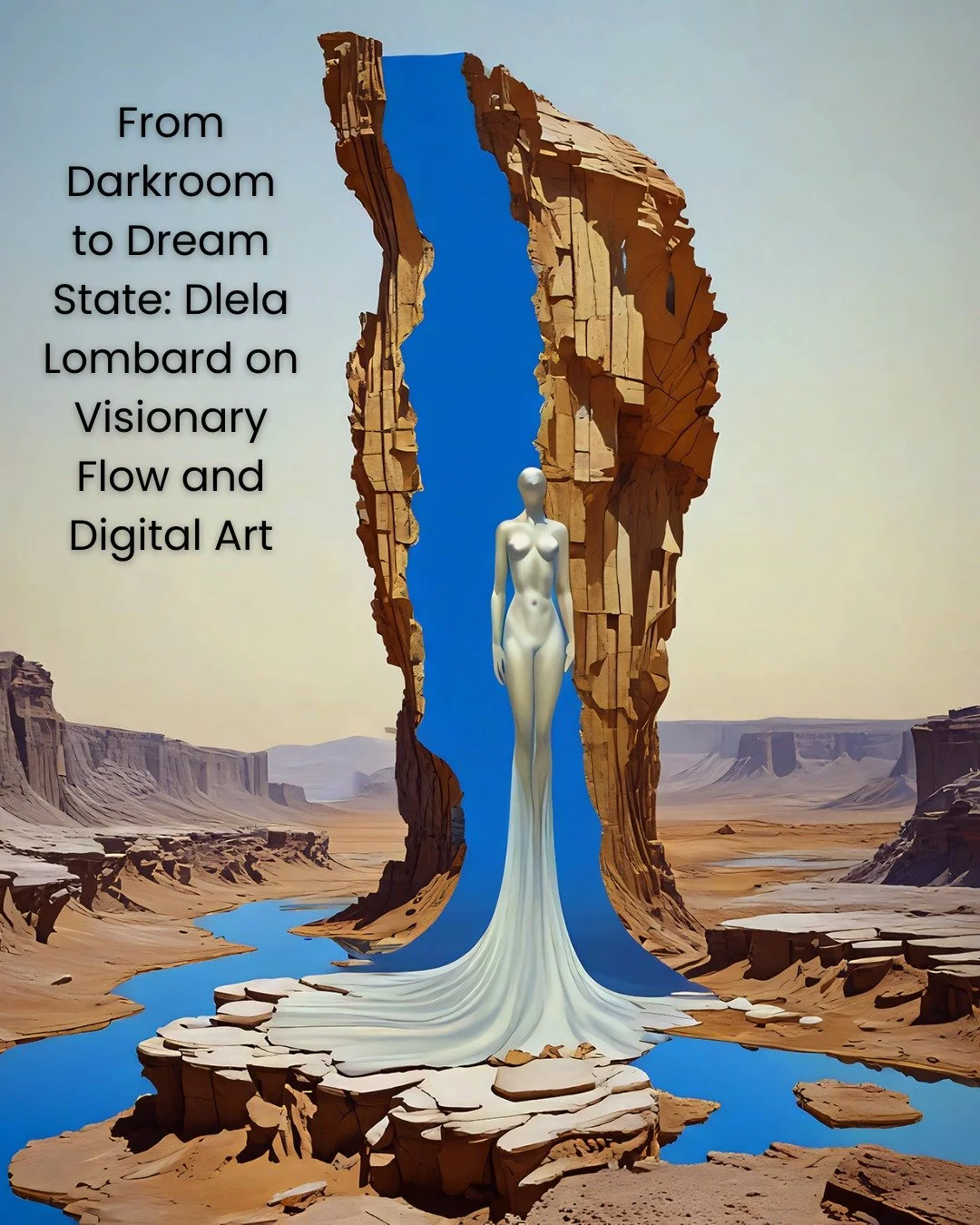

Qiu Xing Ba Shou Cover

You describe visual language as a bridge beyond words. Can you share a moment when your work connected with someone across cultural or linguistic boundaries?

I was invited by a Chinese publisher to collaborate on one of the volumes in their picture book series, for which I created all of the illustrations. The target audience of this series is students interested in classical Chinese poetry. The volume I worked on visually interprets Du Fu’s poem series "Qiu Xing Ba Shou (Eight Poems on Autumn Meditations)," written in his later years. The illustrations portrayed the autumn scenery, the poet's memories of the prosperous capital, his sorrow over unfulfilled aspirations, and his deep concern for the nation's turmoil during the Tang Dynasty.

Even for Chinese students, the complex emotions conveyed in the poems can be difficult to fully empathize with. I aimed to convey the poet’s feeling more directly to the readers through visual images. What touched me deeply was that when I showed some of these pages to people from different cultural backgrounds, they were able to connect with the poet even without text. The sorrowful, patriotic elder profoundly moved them.

This project has been selected as a winner in the 2025 Applied Arts Illustration Awards and received a merit award in the Three x Three International Illustration Awards.

The Cycle

Your art invites viewers into contemplative spaces. What role do you hope reflection or quietness plays in how people experience your work?

I always view the creative process as a form of meditation, and I hope my work can serve as a meditative space for viewers. I want my pieces to function like the resonance of a Tibetan singing bowl, becoming a pause button in people’s daily lives, directing their attention to the feelings and associations brought by the work’s content and atmosphere. The piece I mentioned earlier, “Bury Me,” frequently receives feedback from viewers perceiving in it a sense of “Tao” or “Zen.”

The Day The Seas Disappeared

Who are some artists, writers, or thinkers that influence your way of building poetic imagery?

The first person comes to my mind is Odilon Redon. His surreal, dreamlike, and non-figurative paintings, especially his later works, always lead me to reflect on my own dreams and thoughts and have been inspiring.

Chinese artist Zikai Guo is another person who has highly influenced me. His paintings and ceramic works are often based on traditional Chinese mythological tales. His atmosphere creation and the visual storytelling through various non-human creatures consistently leave a profound impact on me.

Looking ahead, are there new mediums or directions you’re curious to explore in your practice?

I have always wanted to explore combining my digital painting with animation or 3D modeling. Previously, I followed online tutorials to learn basic tools of After Effects and experimented with a simple animation. I hope to learn to use this software more systematically, and also want to try the Live2D format and some more complex animation effects. Learning 3D modeling and transforming my artworks into 3D has long been on my to-do list as well, but for now, I want to focus more on exploring dynamic expression in 2D formats.

Wood Dragon