Jaeden Riley Juarez at the Columbia DSL Student Showcase

By Rosa Matos

On May 5th, Columbia University's Digital Storytelling Lab hosted its Spring Semester Student Showcase at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center. The result was an evening dedicated to projects and conversations that break the boundaries between storytelling, technology, and design.

Including courses such as Digital Storytelling II, Creative Coding, Worldbuilding, and Transformative Storytelling, the event showcased student works that question and reimagine narrative through AI, AR, physical computing, and browser-based experiences. These projects were innovative and deeply personal while also commenting on systems of empathy, creative expression, and collective experiences.

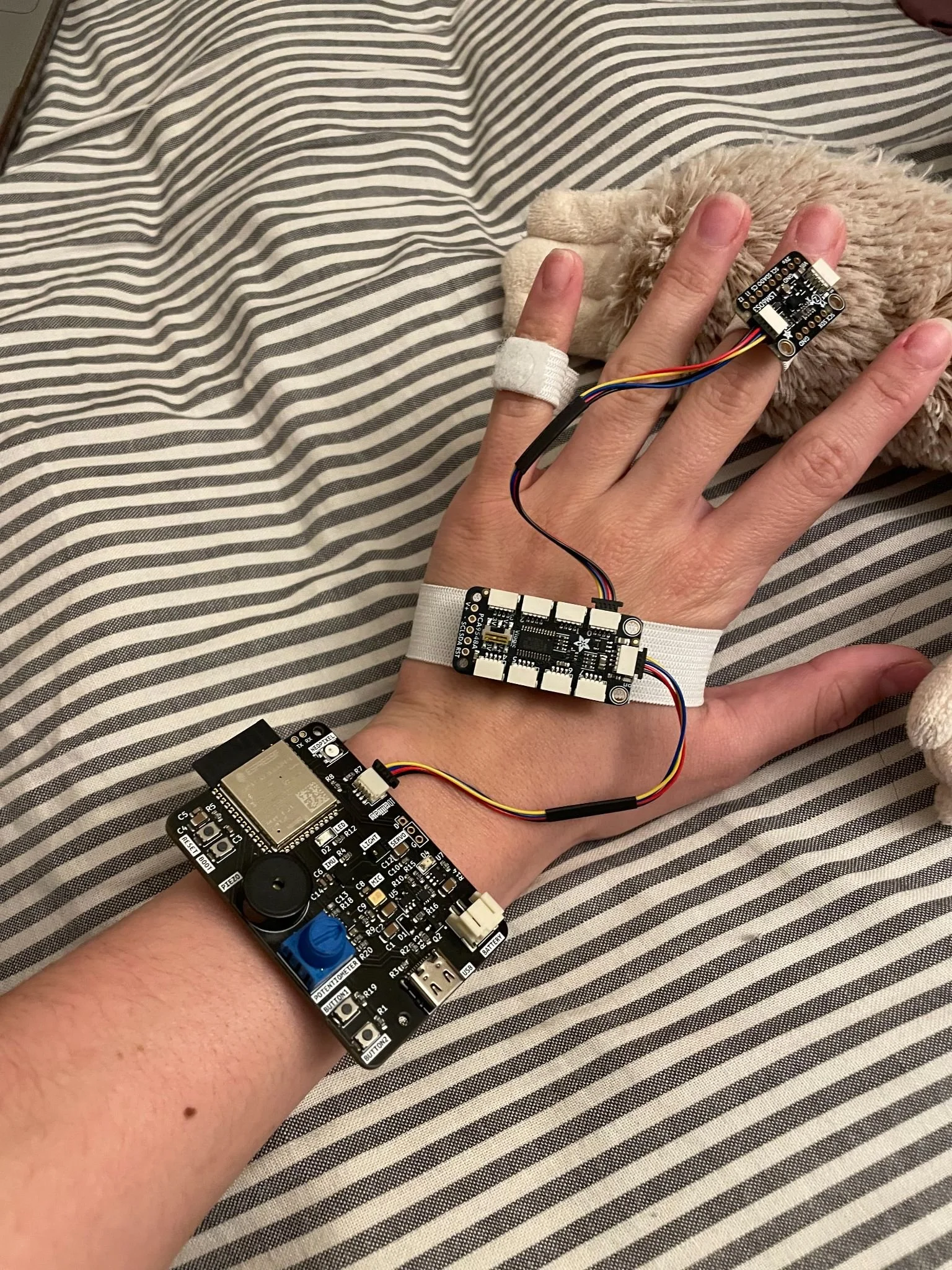

In this feature, we have the opportunity to dive into one of the incredible projects from the evening. Columbia student Jaeden Riley Juarez shares her inspiration, process, and the role of technology in Gesture MIDI Controller: A Wearable Musical Interface, a project she developed in the Creative Coding class.

What first inspired you to create a wearable musical interface? Was there a specific moment or experience that sparked the idea?

I was first inspired to create a wearable interface when I started working as a book writer on my musical, Firehouse. The composer I’m collaborating with, Ben Roe, and I were always looking for a piano, often spending more time trying to find one than actually using it. That’s when the idea of a portable and accessible musical interface became something I was interested in.

The gesture-based concept itself was inspired by Imogen Heap’s Mi.Mu gloves. I was fascinated by how she could manipulate vocal effects, distortions, and pitch bends using hand gestures. That sparked the idea for me.

As someone with a background in acting and music, how do you think about gesture as a form of expression or storytelling?

I’m heavily inspired by spontaneity as an actor. I like having a world and rules to live within, but then being free to explore and respond in the moment. That mindset carried over into this controller. It gives artists a set of gestures, a framework, but it also invites them to be spontaneous, to play, and to discover.

And hands are inherently musical. Most instruments require our hands. Even singers use solfège hand signs to embody pitch. Our hands are fast, coordinated, and expressive making them the perfect vehicle for gesture-based musical control.

How did your experiences as a performer shape the design decisions behind the interface?

As a performer, you’re always trying to take what feels natural and dramatize it. To heighten it in a way that still feels intuitive. That informed my design process. If something looked impressive but didn’t feel intuitive, it wasn’t doing its job.

I think good performance, and good design, both require a strong relationship to instinct. This controller needed to make sense in the body. That mindset came from my experience as an actor and performer.

What made you want to explore the intersection of computer science and performance art? Did this project open up any new ways of thinking about embodiment or interaction?

Originally, I wanted to explore this intersection to create tools for other artists. I didn’t really see myself as an artist whose medium could be technology. But this project changed that. It helped me realize that I can be both a performer and a technologist. Those worlds can coexist and actually strengthen each other.

Can you describe your process for developing and refining the gestures? How did you ensure they felt intuitive and expressive for musicians?

I don’t read music… yet! So I made it a point to work closely with musicians who do. I asked a lot of questions about how they compose, and what their early songwriting process looks like. One thing I kept hearing was that many start with chords and build from there.

That gave me a clear starting point. Since there are seven basic diatonic chords in a key, I decided to create seven core gestures. It was a small enough number to contain within one hand, and the numerical association made them easy to remember.

Throughout the process, I tested with both musicians and non-musicians to make sure the gestures felt intuitive. Could people remember them? Did they make sense physically? That feedback loop was so important.

What kind of feedback did you receive from the musicians you tested with, and how did that influence the final version?

I got some really helpful feedback that shaped the musical and technical sides of the project. One big thing was learning about the importance of root notes in distinguishing chords. That helped me refine how the chords were built and triggered.

Another note I got was about keeping chords within a single octave to support smoother voice leading. That made a huge difference in how natural the output sounded.

And one artist suggested adding a mode for melody instead of just chords. That opened up a whole new layer of interaction. That’s next!

What were some of the biggest technical or creative challenges you encountered in the project?

The biggest challenge was the hardware implementation. Due to the structure of my class schedule, I had two weeks for brainstorming and two weeks for building. I planned for one week for software and one week for hardware. But I quickly realized that hardware is, well, hard.

Between sensor calibration, wiring, and physical testing, it became clear that I wouldn’t be able to finish the hardware side in time. So I pivoted to a fully software-based system. That decision actually ended up being really freeing. It allowed me to focus more on gesture logic and musical output, and made the whole experience more robust and interactive.

Do you see this controller primarily as a performance tool, or could it have broader applications — for example, in education, accessibility, or installation work?

The controller was initially designed more for experimentation than performance. I wanted to create something that helped people, regardless of musical training or accessibility to instruments, explore music creation in a hands-on way.

That said, I’ve always been curious about it as a performance tool. And after sharing the project with others, I’ve realized that the possibilities go far beyond what I imagined. People have suggested using it in education, in accessibility-focused spaces, and even as part of sound art installations.

That’s been one of the most exciting parts, seeing how the project can adapt depending on who’s using it and what they need from it.

What do you hope people experience or feel when engaging with the piece, either as performers or viewers?

I hope people feel not limited. That music creation can be for them. You don’t have to spend years in piano lessons before you can start experimenting and expressing yourself through sound.

As performers, I want them to feel free to play, to explore, to make mistakes. And as viewers, I hope they feel like they want to jump in too. That sense of curiosity.

How has the Creative Coding course influenced your relationship to technology, storytelling, or the body as a site of interaction?

Creative Coding really expanded my concept of what’s possible. I always said I wanted to work at the intersection of computer science and the arts, but before this class, I didn’t fully know what that looked like. Now I do.

This course helped me realize that I can use code as a creative tool. That I can make art with it. I now have a much clearer sense of the tools I can use and the kind of stories I want to tell with them.

Keep up with DSL: