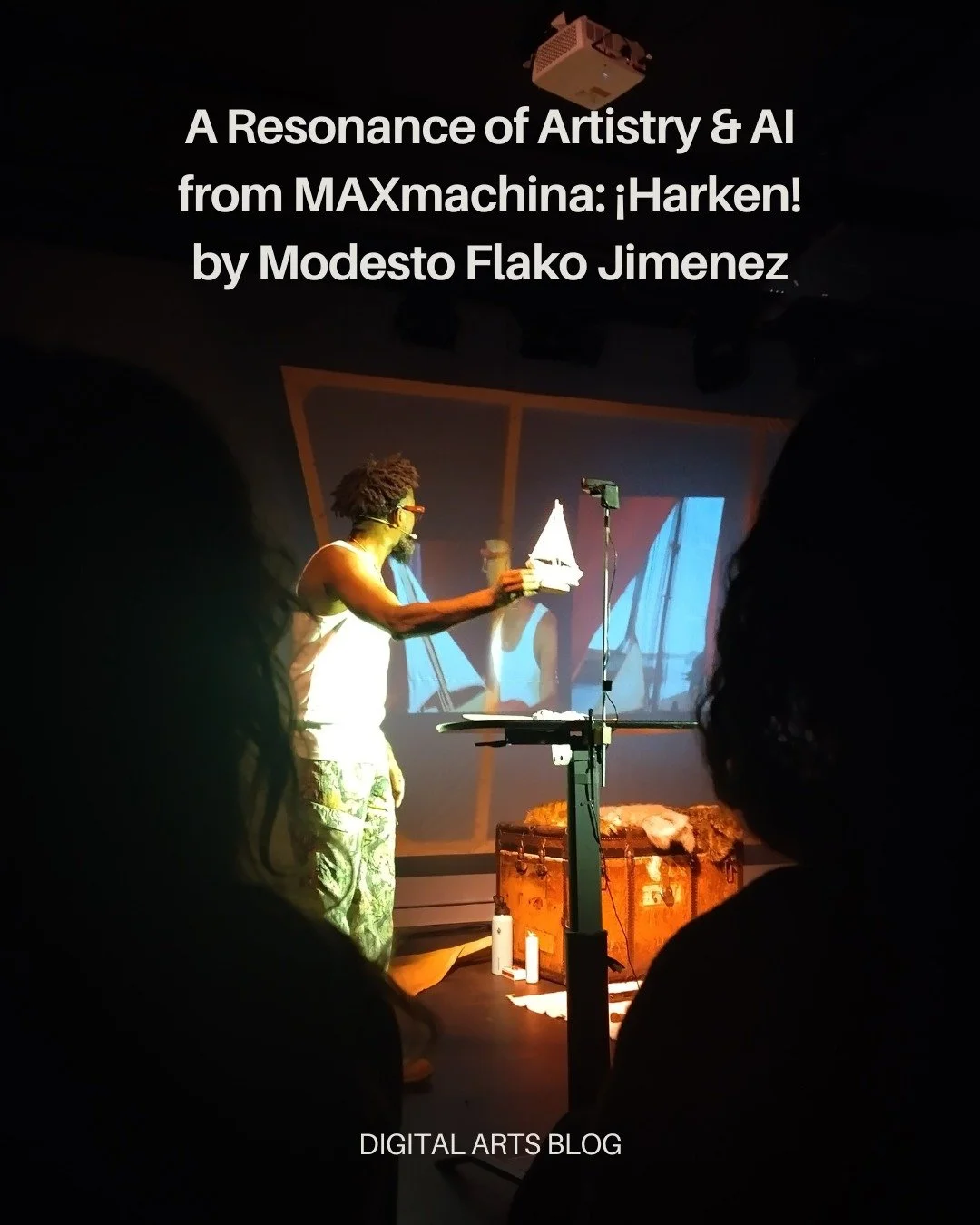

DAMN TRUE on Grief, Glitch, and Staying with Discomfort

By Cansu Waldron

DAMN TRUE works at the intersection of digital decay, memory, and emotional distortion, building a visual language from personal archives, neural glitches, and the raw textures of everyday life. Rooted in contemporary Russian urban experience, his still lifes and portraits hover between presence and disappearance, irony and grief — inviting viewers to sit with discomfort, notice what image culture often smooths over, and find beauty inside the broken.

He came to digital art through image-making rather than technology itself, experimenting early on with tools like Paint and developing an instinct for distortion and visual instability as expressive forms. During his mother’s illness and loss, portraits began fragmenting naturally, reflecting emotional states rather than stylistic choices. When AI tools became accessible, they folded seamlessly into this process;not as shortcuts, but as collaborators, helping DAMN TRUE continue working with memory, archives, and the unstable nature of images in the digital age.

We asked DAMN TRUE about his art, creative process, and inspirations.

Portrait of the Era of Rails and Discounts #7

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

I came to digital art not through technology, but through image and observation. My first experience with digital image began long before the advent of neural networks, with simple tools like Paint, where I intuitively explored form, distortion, and error as part of a visual language.

Over time, working with images became a way for me to capture my personal experiences. During the time of my mother's illness and loss, the portraits began to change: they became fragmented, distorted, and unstable. These transformations were not a stylistic device; they reflected an inner state and the impossibility of preserving the image in its entirety.

When artificial intelligence became an accessible tool, it seamlessly integrated into my practice.

I continued to develop the series I had started, working with archival fragments of photographs from my life and the lives of those close to me. The digital environment became a natural space for me to work in, as it is where collective vision and memory are formed today.

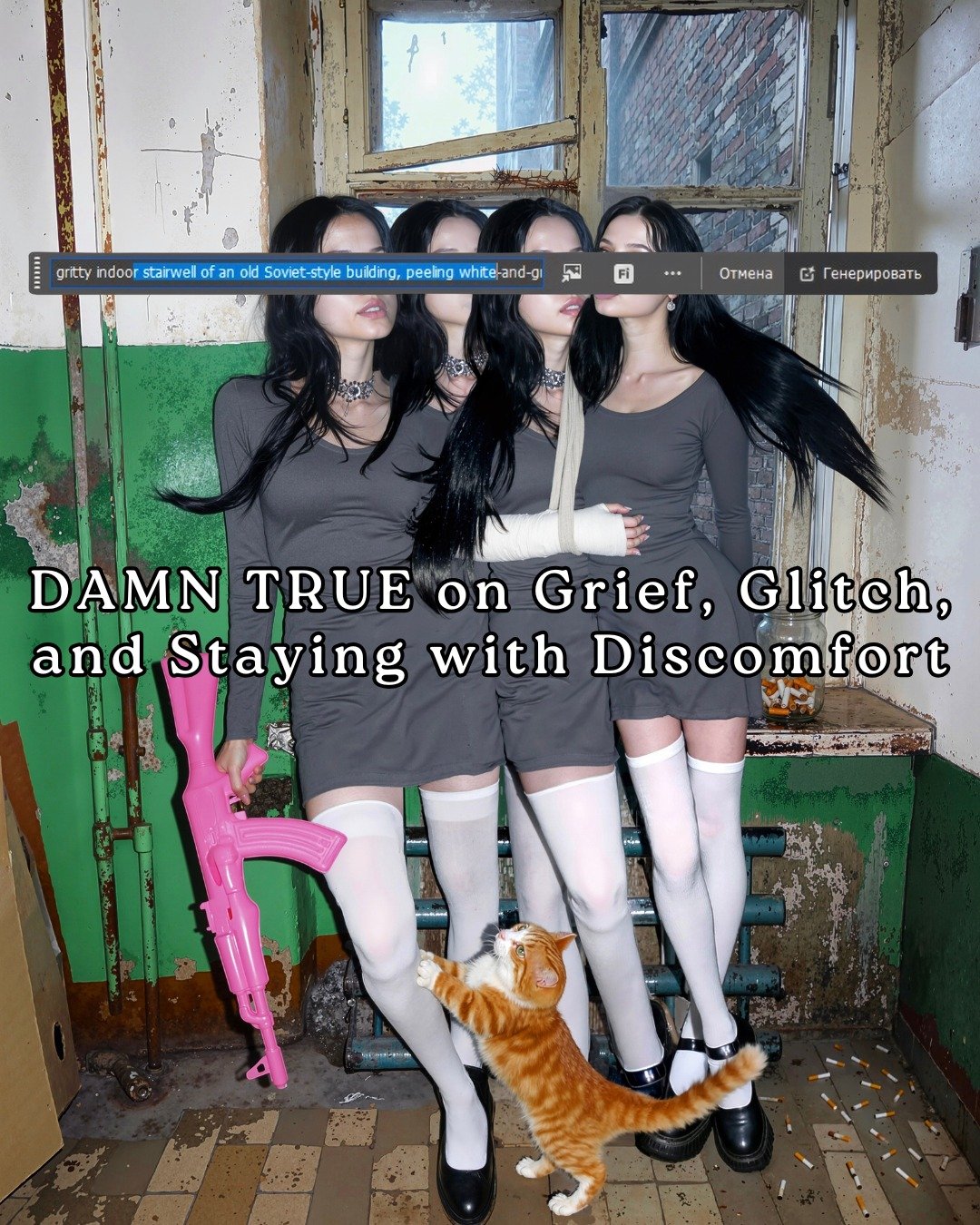

When you work with AI, what kind of resistance are you actually looking for from it?

I'm not interested in AI as a tool for achieving a perfect result. Instead, I'm looking for moments where the system begins to resist making mistakes, simplifying, distorting, or offering overly obvious solutions.

This resistance is important to me because it reveals the boundary between intention and interpretation. AI becomes not an assistant but an environment where discrepancies arise. These failures and inaccuracies often reveal more truth than a smooth image, as they expose the machine's thought process and my encounter with it.

Portrait of the Era of Riles and Discounts #8

Have you ever abandoned a piece because it felt too close — or not honest enough?

Yes, it has happened. Sometimes a work may be technically complete, but internally it may not be honest. Sometimes an image may be too close, almost painful, for me personally or for society, and then I realize that it needs time or distance before it can be published.

I am not afraid to reject a work. For me, accuracy is more important than completion. If an image stops being honest with my inner state, I prefer not to publish it, and therefore I have many drafts and unfinished works on my computer that I may return to in months or even years.

Still Life of the Rils and Discounts Era #14

Contemporary image culture moves fast, but your work asks viewers to slow down. Do you feel at odds with the speed of the platforms where your work circulates?

Yes, this conflict exists, and it is a conscious one. I use fast platforms to talk about slowing down, paying attention, and pausing. My work is within the flow of images, but it does not fully belong to it.

It is important for me to create tension between the form of distribution and the content. Scrolling is our reality, but it is still possible to require the viewer to stop and take a thoughtful look.

I add a lot of different details to my work to make people take a breath and look away from the fast-paced content on the internet.

Do you feel like you’re documenting your surroundings, or coping with them?

Rather, it's both. For me, documentation is a form of adaptation and a way to avoid getting lost in the moment. When reality becomes too fragmented and noisy, documentation becomes a way to stay connected to myself, time, the news cycle, and archival memories.

I don't strive for an objective document. Instead, I'm interested in the subjective trace, the way reality passes through perception and leaves an imprint, as the images in my paintings are sometimes readable but also imperfect and sometimes fictional.

UN[TITLED] ##32

What is a profound childhood memory?

From a very young age, I was immersed in creativity. I didn't have a lot of modern toys or ready-made game systems, so I was constantly creating my own worlds on my own. They weren't "polished" or visually perfect like those of large companies, but that's what made me imagine, complete, and complicate them.

I remember sitting in my room for hours, assembling another world from improvised materials, coming up with rules, structure and internal logic for it. These worlds were constantly being rewritten, destroyed, and re-created. At the time, I didn't realize how significant this experience was, but it shaped my habit of working with images as a space for thinking, rather than just as a beautiful form.

Today, I see clearly that these childhood attempts to construct my own realities have become the foundation of my artistic practice, driven by a desire to create, explore, and reassemble worlds, even if they exist only as images.

What else fills your time when you’re not creating art?

At different times in my life, I have been involved in a wide range of activities. In the past, I worked as a waiter, and contrary to expectations, I actually enjoyed this job. The constant interaction with different people, the casual conversations, and the stories they shared became an important source of inspiration for me. It was during this period that my pseudonym, DAMN TRUE, was born as a reaction to the moments of unexpected, genuine truth that sometimes arise in the most ordinary situations.

In addition to this, I am also interested in archaeology in my free time. I like to go out and study dinosaur fossils — to work with material traces that have survived for millions of years. This activity helps me to step outside of the digital environment and to shift my focus to a completely different time scale.

Sometimes, you really need to get your head out of the digital art and into something radically different. This contrast between digital images and physical traces of the past feeds my artistic thinking in many ways.

UN[TITLED] ##33

What is a dream project you’d like to make one day?

I would like to implement a project dedicated to the memory of my mother, who is no longer with us. I see it as an archive with a rebirth in the modern digital environment — a space where personal memory connects with technology and time.

In this project, I would like to record the results of my artistic work in recent years after her departure, as a kind of dialogue that continues beyond the physical presence. It is important for me to leave this project with an open ending, not as a conclusion, but as a continuation. It suggests that memory does not stop, and that through new works created in the future, it continues to live and witness my journey.

This would not be a memorial in the usual sense, but a living, evolving archive where the past and the present exist simultaneously.

Have there been any surprising or memorable responses to your work?

It is especially interesting for me to receive feedback at exhibitions when I communicate with people who do not know that I am the author of the works. At such moments, we look at the works together, and this is what creates the most honest response without personal attachment, without expectations.

Sometimes viewers shared their experimental impressions: they say it's interesting and important to look at it in a gallery or museum, but it's unlikely to hang such a work at home. This is also important information for me, because it shows how my works live in different contexts and how they are perceived regardless of my presence.

UN[TITLED] ##39