Between Algorithm and Memory: Pioneering Digital Artist Martine Jacobs on Early Internet to AI

By Cansu Waldron

Martine Jacobs is a Dutch artist whose work moves between the digital and the handmade, blending AI generation with delicate pastel interventions. Her recent series, Four Hybrid Works: Between Algorithm and Memory, explores what happens when beauty, once central to art, begins to fade into memory. Each piece starts with artificial intelligence and ends with her touch — a quiet act of resistance that brings warmth and humanity back into the machine-made.

For Martine, technology has always been both a promise and a warning. From her early days battling with a Pentium II in 1998 to today’s AI tools, she’s witnessed the digital age evolve from struggle to near-limitless creation. Yet her newest works carry a deep melancholy: a reflection on how freedom, compassion, and truth feel increasingly fragile in a changing world. Through her dystopian yet tender imagery, Martine reminds us that beauty still matters — not as nostalgia, but as a form of courage.

We asked Martine about her art, creative process, and inspirations.

Can you take us back to the late 1990s — what first drew you to making art on and with the Internet?

The late 1990s—specifically having access to one of my first personal computers, a Pentium II in 1998, coupled with basic software like early Adobe and PSP (Paint Shop Pro)—was a moment of complete liberation.

My foundation was classical; I was trained at the Amsterdam Art Academy, deeply rooted in charcoal and pastel work, and the classical setup of composition on paper. The computer, however, immediately opened a world without limits. I saw endless possibilities in digitally manipulating images; every thought and every flash of inspiration I had, I could instantly search, download, and transform using those early programs.

This shift was met with significant resistance. My art colleagues and peers often gave me pitying or outright dismissive looks. The consensus at the time was, "The computer can never replace the artist," and that digital art was "one-dimensional." But I felt I was breathing life into what others saw as cold, computer-generated work by channeling it through the warmth of my pastel technique.

I quickly realized the sky was the limit. I could take on commissions like a unique Renaissance series. I created digital designs and then executed them as strikingly colorful pastel drawings. The work was fiercely criticized—"How dare you process such masterpieces into a new form of digital art?" My answer was simple: I was retrieving these works from dusty museums and giving them back to the public in my own way.

I had no illusions; I knew critics would scorn my early experiments. Yet, the strong belief that digital art was the future, kept me experimenting. My ultimate goal was to take the basic digital image and transform it into a piece of art that felt alive and physically warm through the soft texture of pastel.

It was a profound, defiant experiment.

You’ve described your works as “Archaeological Internet Art.” What does that term mean to you, and how does it frame the way we should look at your practice?

For me, "Archaeological Internet Art" is a profound acknowledgement of the materiality of digital decay. When we look at works from that early era, we're not just looking at images; we are looking at digital ruins—pieces of obsolete code and software aesthetics that are fading away. The term forces us to view this work through a historical lens, like a found ruin or a relic.

It means two things for my practice:

It demands that the viewer accepts the low-fidelity aesthetic and the technical limitations of those early programs as part of the work’s identity and history, not as a flaw.

It frames my work as an urgent mission to find and preserve the most fragile evidence of our collective online emotional history before technological obsolescence makes it impossible.

Crucially, in that environment, no one else was bridging the gap the way I was. While other pioneers were focused purely on code, I was intentionally creating a hybrid artefact. My method was to blend the warm, physical texture of pastel with the cold, fragile reality of obsolete software. This fusion of the eternal and the ephemeral is what makes the work an exceptional problem case for conservation today, and ultimately, a unique document of that era.

Many of your projects explored grief and collective mourning online — why did the Internet feel like an important space for those emotions at the time? And now that your works have been formally taken into the care of the Internet Archive, how does it feel to see them preserved after years of fragility and risk of loss?

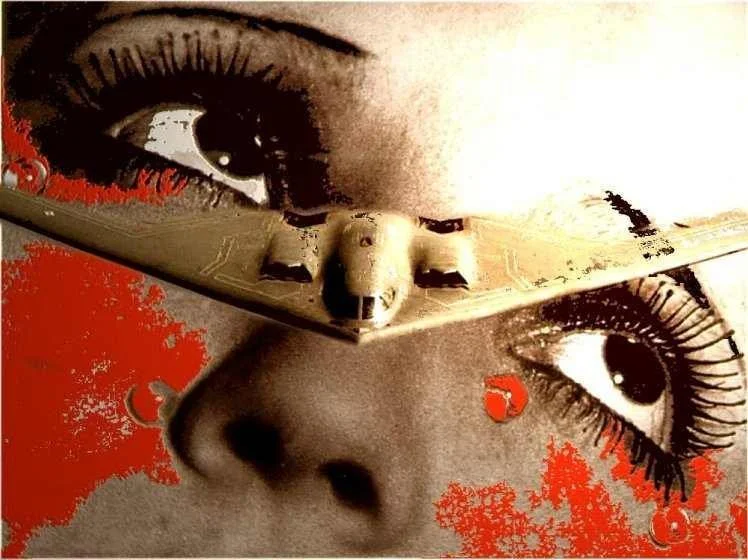

I am a sensitive person; I have always struggled deeply with injustice and the profound suffering people inflict upon one another. The historical low point, for me, remains the incomprehensible crimes against humanity during the Second World War. I created a portrait of my compatriot, Anne Frank, placing her beside a Buddha as a symbol of the compassion that failed her. My question was: Where was the compassion?

Art became my vital outlet. When the threat of the first Gulf War arose, and I heard an Iraqi minister say, "The women will cry blood"—a devastating statement about the ultimate cost of conflict—I created a digital design, realized in pastel, as a fierce protest against war and megalomania.

When the internet arrived, it offered a revolutionary, raw space for this collective feeling. Traditional media and society struggled to process large- scale grief; the internet provided an anonymous, immediate, and horizontal sanctuary. My work proved that this deep human need—to share pain and seek comfort publicly—existed and thrived, attracting over 100,000 unique visitors pre-social media.

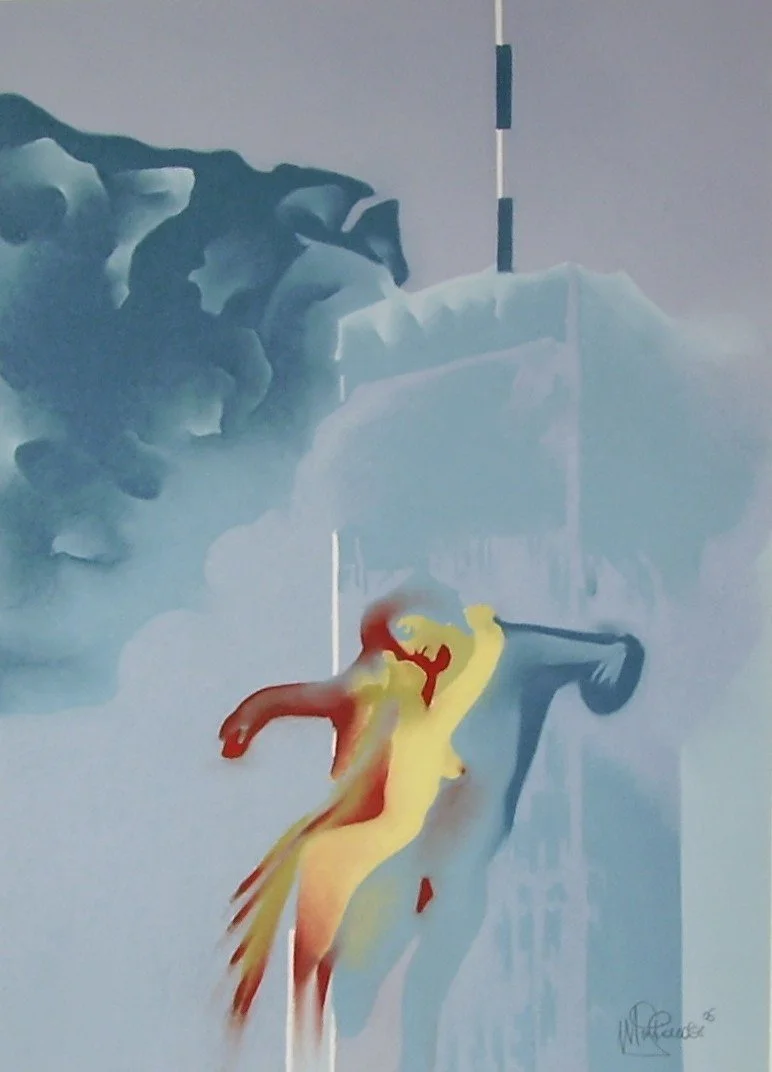

Years later, when New York suffered the unimaginable tragedy of 9/11, I was devastated once again. My ultimate expression came with my 'Shared Grief' series. I consciously combined the horror of the New York Twin Towers attack with the devastating legacy of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. My aim was to convey that sorrow and human suffering are universally the same— there is no difference in the magnitude of the grief, whether it is Hiroshima or New York.

After years of fighting against technological decay and the risk of this emotional history being lost, having my works formally taken into the care of the Internet Archive feels like an immense relief and an institutional validation. The Archive secures the proof of the emotional resonance and the historical document I created. It transforms the work from fragile code into a permanent, recognized historical asset, allowing the focus to shift entirely to the work's message—the enduring need for empathy and the shared nature of human suffering.

What are the challenges of preserving early net art that was built on technologies no longer supported today?

The immediate, technical challenge—simply saving the files—is the easy part. The real difficulty lies in preserving the context; it is the fight against what I call contextual obsolescence.

My works present a particularly acute problem because they embody a unique hybridization. They blend the soft, analog texture of pastel—a material meant to feel warm and physically permanent—with the rigid, low-fidelity aesthetic of obsolete 1990s software and early web browsers. This fusion is where the historical meaning resides, and it is precisely what is hardest to save.

To elaborate on the challenges:

The Loss of "Digital Atmosphere": Early net art relied on slow bandwidth and low-resolution CRT monitors. When viewed on a modern, high-resolution screen, the work looks fundamentally different. The challenge is fighting the emulator decay—we are struggling to maintain the specific visual and temporal experience of the work.

The Hybrid Conflict: The work is an exceptional problem case for conservation. It is not just saving digital code (a technical mandate), but documenting how that code was intended to interact with the physicality of the pastel texture.

The Institutional Mandate: Ultimately, preserving this work demands far more than simple data storage. It requires a strategic institutional commitment—a curatorial mandate—to document the exact original software, the required hardware, and the social context of the original viewing experience. Without that commitment, we don't just lose data; we lose a crucial, nuanced piece of art history.

What do you hope contemporary audiences notice or feel when revisiting your work now, decades later?

I truly hope audiences notice the immediacy and the raw humanity of the connection that was possible then. My projects on shared grief succeeded because the internet, in the late 90s, was a space without a clear script. It allowed for an honest, unmediated exchange of deep emotion.

Revisiting the work now is like finding a digital artifact of genuine vulnerability. I hope it forces audiences to look at their own highly curated and commercialized social feeds and ask tough questions. We share grief today, but that emotion is often constrained by a platform’s limits and tied to its profit model.

My work should evoke a certain nostalgia—not just for the low-fi aesthetic, but for a time when the digital space felt genuinely open for deep, shared human experience. I hope they feel the authenticity that is often missing when emotion is processed through the economics of current online engagement.

Do you think there’s a generational gap in how people experience early net art versus newer digital-native practices?

Yes, a huge gap certainly exists for the general audience, and it is primarily rooted in agency.

Early net art was often about the act of building and actively seeking out those singular digital places. Newer digital-native practices are often about consumption and interaction within platforms that have rigid, pre- determined structures (like Instagram or TikTok). Early art was about the possibilities of the web; newer art is often a critique of the limitations and structures imposed by those platforms.

However, for me, personally, that gap is non-existent.

My early digital work transitioned seamlessly into the AI revolution. Everything I had to technically struggle for in the late 1990s—the digital manipulationand complex image processing with limited software—has now been made fluid and immediate by AI.

Now, at almost 70, I feel completely fulfilled by the AI revolution. It's the dream I first had on my Pentium II finally coming true. AI is not a limitation; it is the ultimate realization of the boundless possibilities I envisioned decades ago. Everything is coming full circle. I am thoroughly enjoying the miraculous images I generate in partnership with AI.

What is a profound childhood memory?

As I've grown older, images from my youth have become incredibly clear, defining moments that shaped my entire artistic journey. The divorce of my parents was a major shock, especially because it resulted in me being sent to a strict, Roman Catholic boarding school. This became a profound shadow over my life; there was a chilling absence of affection, and the cruelty of certain nuns—who resorted to humiliation and even sexual abuse—left me profoundly insecure and struggling to find my own identity. I felt hollow, like a bamboo reed swaying with every wind.

The music and culture of the 1970s became my lifeline and my anchor. Later, when I met my life partner Hans in 1973, I had blossomed into what I’d call an original 'culture hippie.' We embraced boundless freedom. Our great journey began with overland travel, culminating in the ultimate hippie dream: reaching Kathmandu, Nepal, in 1978.

My object of study became Eastern philosophy. We found a guru, spent time in orange robes in Pune, India. This experimentation with life itself transitioned seamlessly into my art. I had found an inner liberty that proved invaluable, allowing me to be utterly fearless and unconventional in both my art and my life. That enduring pursuit of unfettered freedom, born from that restrictive childhood shadow, became the core strength of my pioneering digital work.

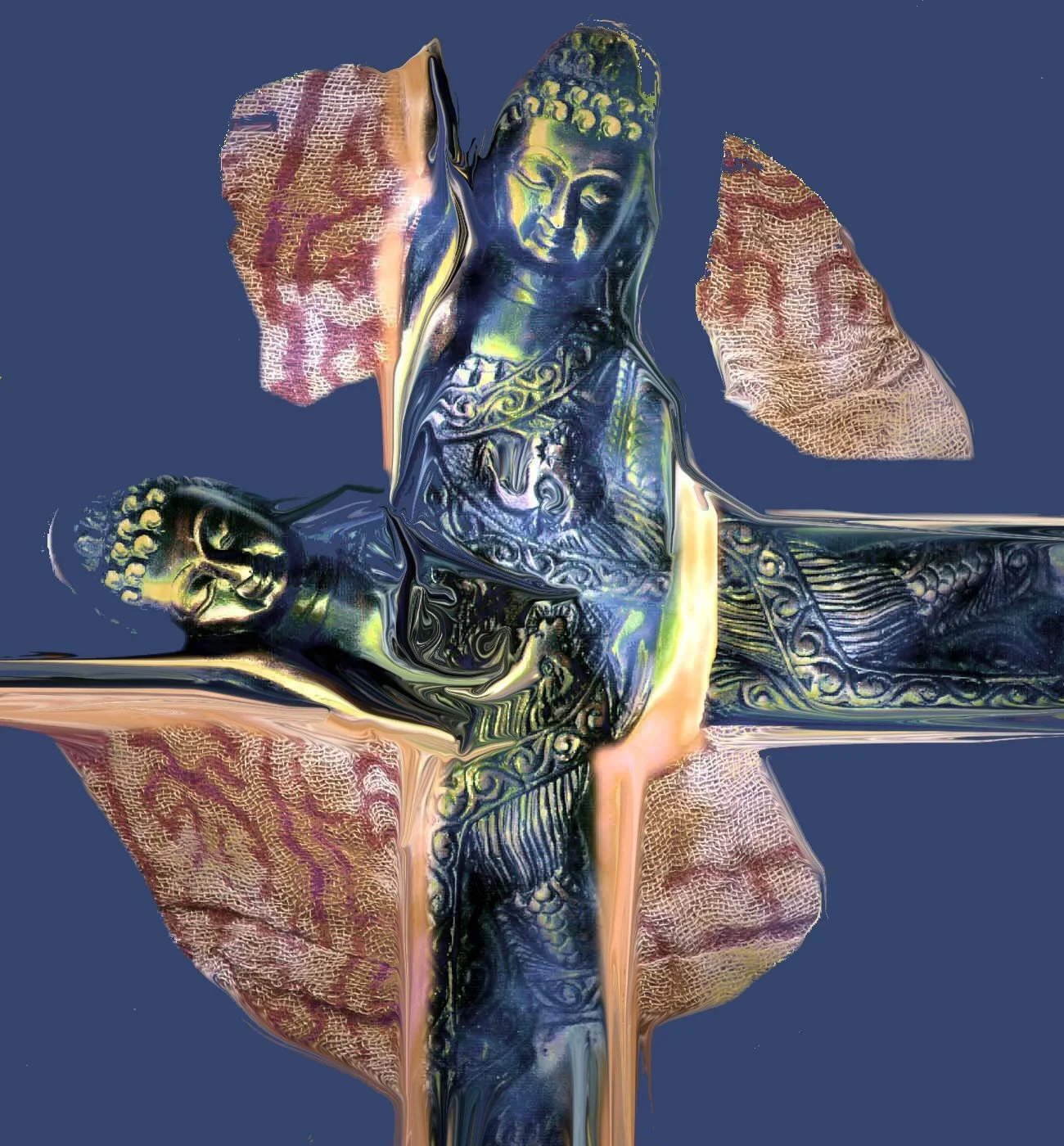

Title: Who’s Afraid of Buddha

Artist: Martine Jacobs

Medium: Digital Art

Year: 2004

In this work, Martine Jacobs places the Buddha in an unexpected and confrontational context. The intense red sharply contrasts with the soft yellow of the Buddha statues, creating a charged and almost provocative image.

The title, "Who’s Afraid of Buddha," plays with the question of fear and spirituality: Does the image of the Buddha evoke tranquility, or does it trigger resistance? The work examines the boundary between devotion and confrontation, between serenity and tension.

In the early years of digital art, Martine found it particularly interesting to mix diverse sources to create eclectic compositions. In this piece, she playfully references Barnett Newman’s famous painting, Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue. By incorporating this art historical citation, she poses a stimulating question: Is this a tribute, a dialogue, or an outright provocation?

The result is a hybrid visual language that evokes both art historical echoes and personal reflection, through which Jacobs investigates how spiritual icons function within a contemporary, digital context.

Artist Statement:

“The Dystopian Turn (2024–2025)

The circle is now complete. The digital struggles I faced on my Pentium II in 1998 are long gone; today, I work with AI, where every thought, every dream, can be instantly rendered. AI is the realization of the boundless potential I first envisioned. Yet, with this technological freedom comes a profound new grief over the vulnerability of beauty itself.

The End of Engagement

For decades, my art was characterized by protest and engagement. Expressing my dissent through art felt commonplace. Today, my newest works are an expression of sorrow because freedom itself is under pressure. People are retreating, afraid to speak out, knowing they have so much to lose. But as I argued in interviews twenty years ago about my protest art: If you must remain silent out of fear, you have essentially already lost everything.

My works are no longer about specific events; they address a deeper, more chilling reality. In Europe, and even in my own country, the once-free and liberal Netherlands, fascism is advancing. Compassion is suddenly seen as a sign of weakness; the lie reigns, and the love for our fellow human beings is being abandoned. Christ is losing his light.

Beauty as a Warning

My current work is, to my great sadness, dystopian. My artistic journey has led me to a point where beauty and high art are becoming merely a memory of better times.

Memory of a Golden Time and Graffiti Spirit reflect this sorrow. They depict great art as a relic, abandoned in a decaying landscape, overshadowed by a darkening sky.

With AI by my side, I am who I am. My art serves once again as an urgent warning: Beware, the freedom of expression may no longer be taken for granted.”

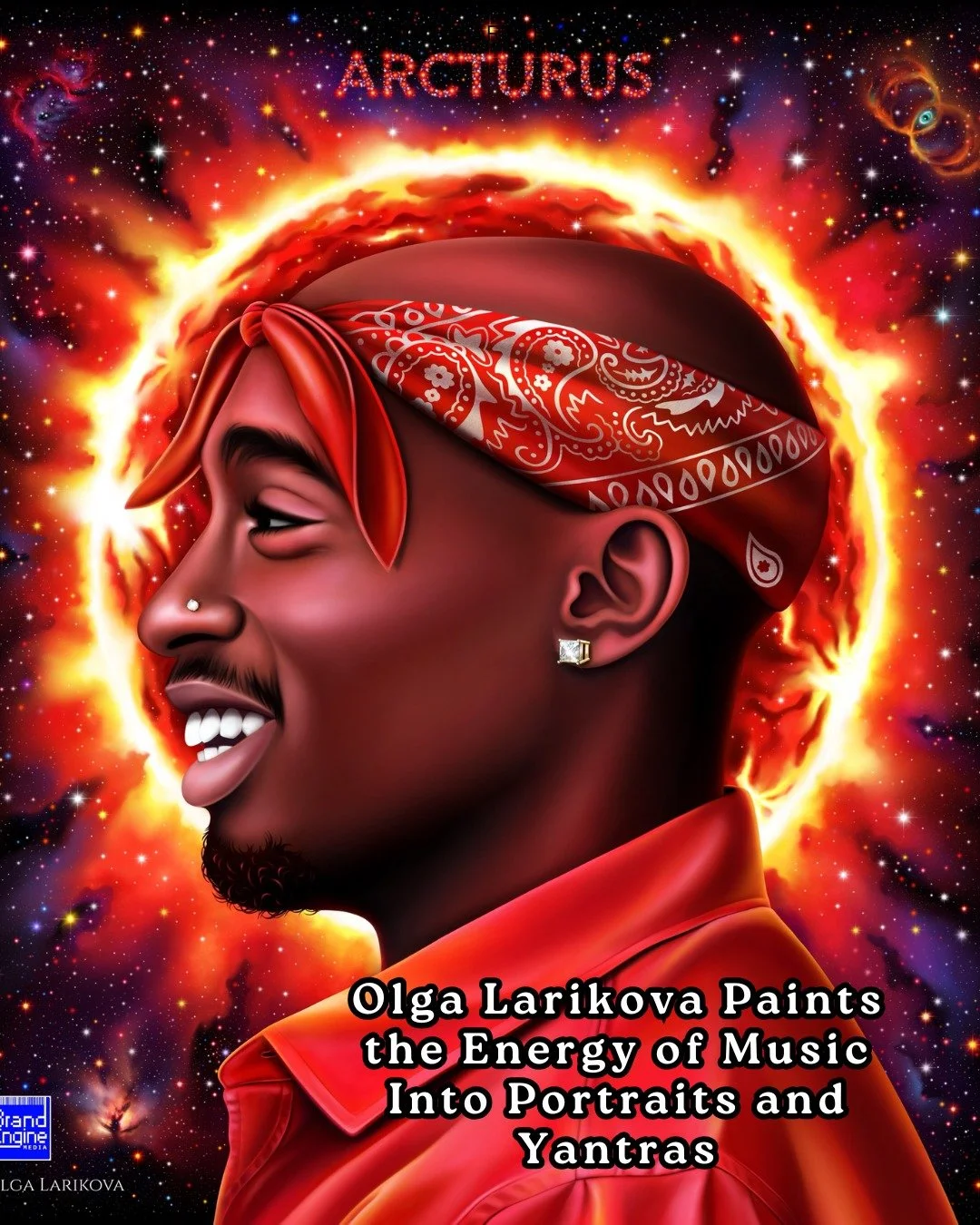

Four Hybrid Works by Martine Jacobs – Between Algorithm and Memory 2025

In her latest series, Martine Jacobs presents four hybrid works that explore the threshold between digital generation and analogue intervention. Each piece is created in collaboration with artificial intelligence, then printed at 42 x 30 cm and hand-colored by Jacobs using pastel pencils — a tactile gesture that softens and deepens the digital origin.

These works are not illustrations of technology, but testimonies of an artistic journey in which beauty and high art are fading into memory. As Jacobs herself writes: “My current work is, to my great sadness, dystopian. My artistic journey has led me to a point where beauty and high art are becoming merely a memory of better times.”

This emotional undercurrent is palpable in Memory of a Golden Time 4 pieces that depict iconic art as relics, abandoned in crumbling landscapes and overshadowed by darkening skies. The juxtaposition of classical masterpieces with decay evokes a sense of mourning for cultural ideals lost to time.

Jacobs’ hybrid works are not visions of the future, but archives of loss — of beauty, of ideals, of a golden time slowly fading. Yet in every pastel stroke, there is also resistance: an attempt to re-enchant the digital, to make memory tangible again.