Digital Art Before the Internet: Victor Acevedo on 40 Years of Digital Experimentation

Victor Acevedo is one of the early pioneers of desktop digital art, creating fine art images and videos with computers since 1985 — long before digital art became mainstream. His journey began even earlier, in 1983, when he started experimenting with computer graphics under the influence of legendary artists Frank Dietrich and Tony Longson. Rooted in geometric abstraction yet often intertwined with figuration, his hybrid imagery carries a metaphysical sensibility that bridges technology, philosophy, and form.

Over the decades, his work has explored synesthesia, cymatics, and Buckminster Fuller’s Synergetics, resulting in mesmerizing Electronic Visual Music (EVM) pieces that merge drone soundscapes with visual geometry. A Los Angeles native, he studied at the University of New Mexico and ArtCenter College of Design, later teaching at New York’s School of Visual Arts for over a decade. His art is part of major collections, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, and has been featured in key histories of digital art. Today, he continues to experiment with new platforms, bringing his pioneering spirit to the blockchain and web3 space.

We asked Victor about his early experiments, creative philosophy, and how he continues to shape digital art’s evolving story.

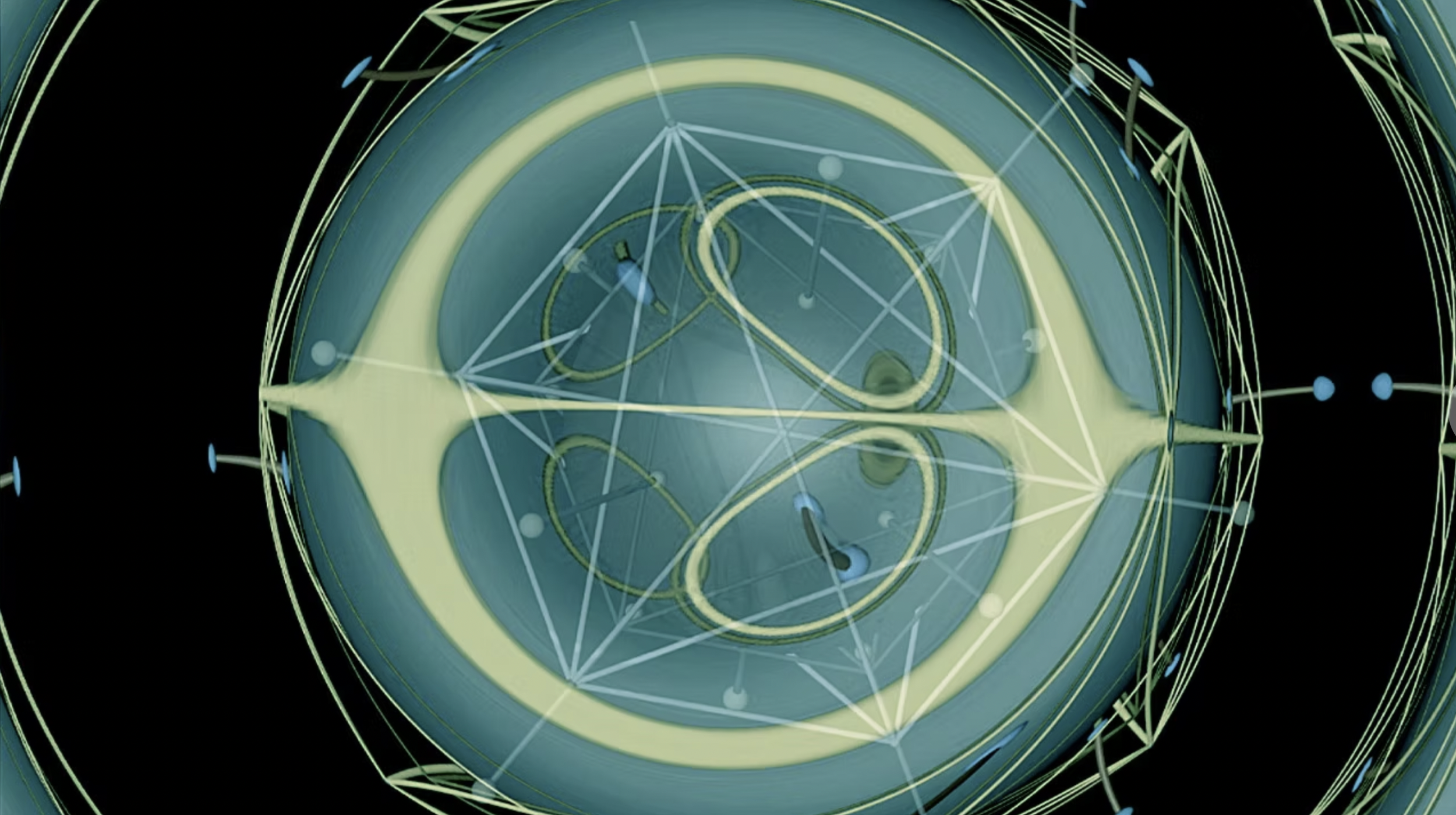

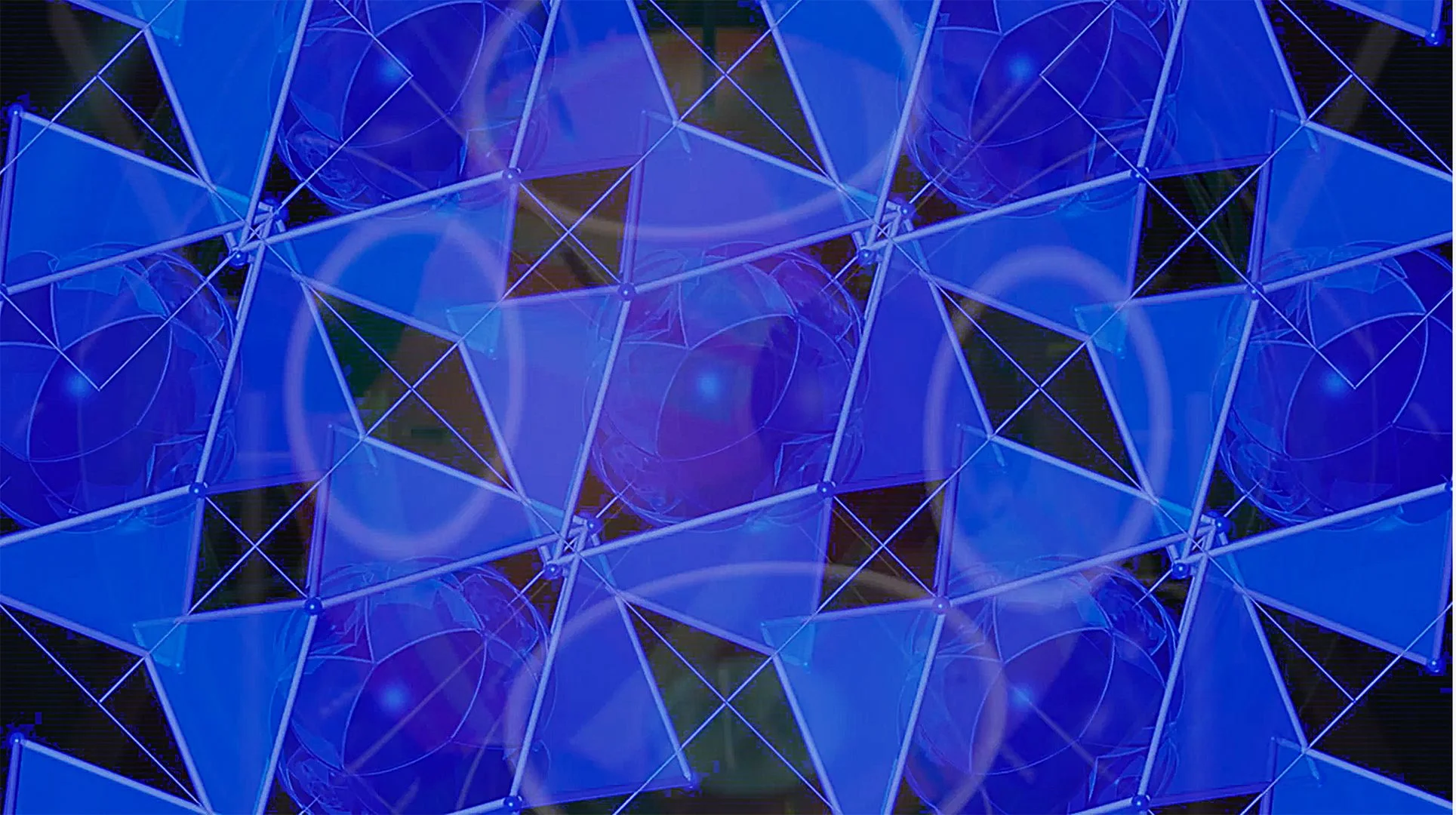

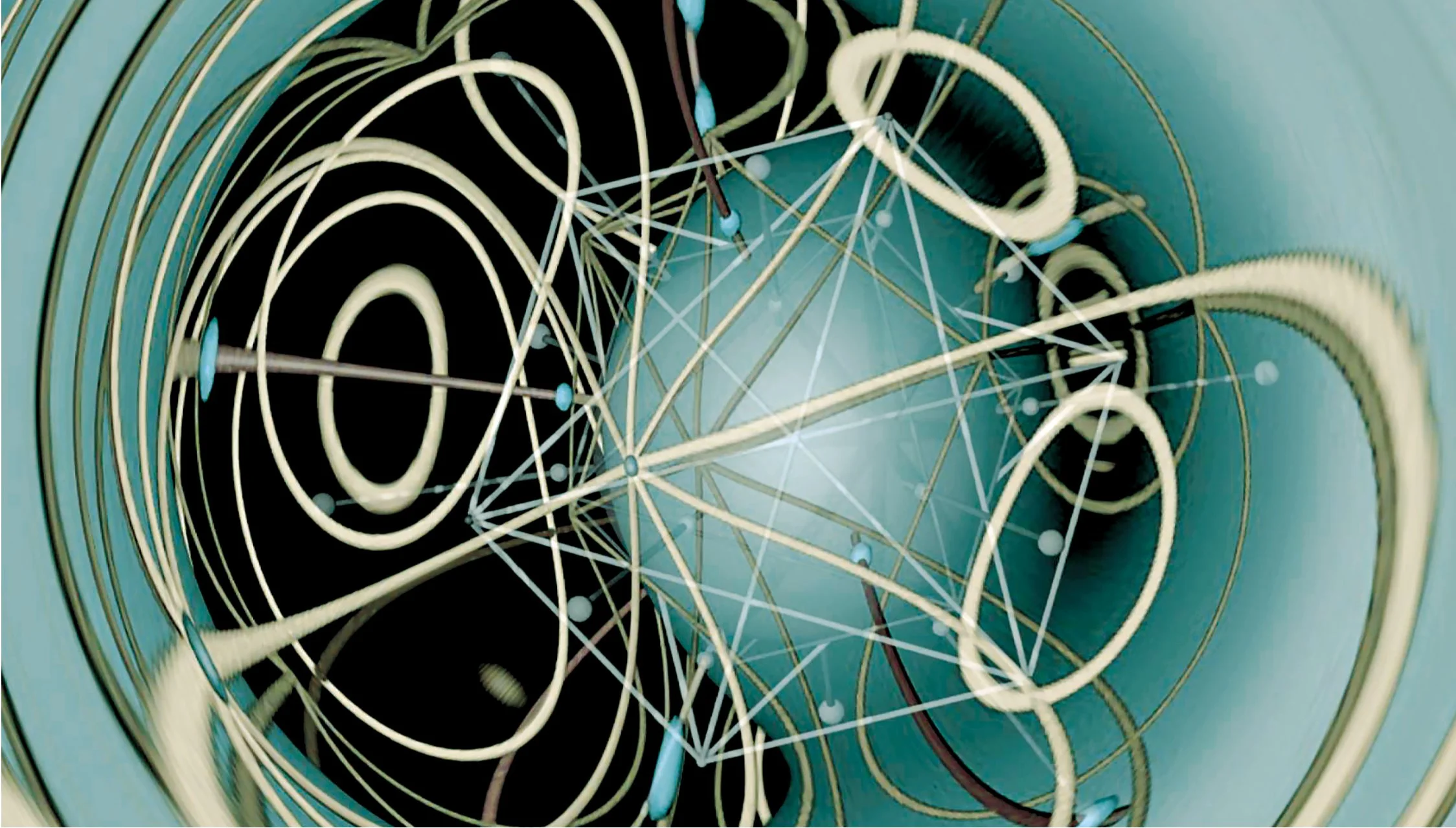

Life Form v01. Still image from the video called Recordings v02 date created: 2016 © 2021 Victor Acevedo

You began experimenting with computer graphics in the early 1980s, well before most people even had a personal computer. What drew you in so early?

Thinking back to that time I feel what drew me in was the result of a combination of various factors. Some childhood experiences with art, science, science fiction, and ‘futuristic’ prosumer technology made me predisposed to an epiphany by learning about computer graphics, whilst still very much immersed in analog media as a student artist.

I first learned about computer graphics when I was attending ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California. In 1980, I took a class with author and media theorist Gene Youngblood. It was based on his seminal book called Expanded Cinema. In this class, I also learned about visual music, telepresence, and the digital video experiments of Steina and Woody Vasulka. It was a life-changing experience. I knew then that I had to get into using digital tools, even though I had never used a computer before. It was clear computer technology had applications across many media. In fact, there was already a genre called “computer art”. Digital media clearly pointed to the future.

Bear in mind this was only a survey class, ArtCenter and most art colleges at that time did not yet have studio courses for computer art and design. This was right before the proliferation of the personal computer and let alone sophisticated or professional level graphics software that could run on them.

It was all totally new to me, at the same time totally relevant to what I was interested in and where I was at on my artist path. My personal focus was on art and geometry such as the zoomorphic tessellations of M.C. Escher and the polyhedral and geometric musings of Salvador Dali which augmented his surrealism. I could see that the fundamental or underlying language of computers and digital graphics was mathematics and geometry. I figured the kind of pictures I wanted to create would be facilitated and greatly expanded by digital technologies.

Slated Breakfast: Visceral Analytic (crop) Graphite on paper November 1980 © Victor Acevedo

I completed my studies at ArtCenter a year later, and I then actively sought out getting access to, “hands-on” as we used to call it, with “computer graphics”. That led me to a weekend workshop with Frank Dietrich in 1983 and then a full-length class at West Coast University in Los Angeles with Tony Longson in 1984. These classes stressed an algorithmic (programming) approach to image making.

Digital Paint Study (1985) created on a PC True Color Paint system © Victor Acevedo

Do you recall a specific moment or lesson that shaped your direction?

A moment like that occurred in Gene Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema class. It was seeing Ed Emshwiller’s short computer animation video called Sunstone (1979) for the first time. It had been produced in collaboration with computer scientists at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT). I had never seen anything like it before. It’s very simple by today’s standards but in 1980 it was relatively cutting edge. I thought it was fantastic! Although it was being delivered on video it wasn’t just a video, it was some other thing. It seemed like time-based painting. It had animation, image processed live action, color-cycling, and moving perspectival three dimensionality.

You can still see it on YouTube.

This was the experience that confirmed for me that computer graphics and thus computer or digital art was the future, and I wanted to get into it. That momentary episode shaped my direction as you might say.

What was it like studying with Frank Dietrich and Tony Longson?

My first hands-on experience with computer graphics was in 1983, I took a weekend workshop taught by pioneering computer artist and theorist, Frank Dietrich which was held at the Long Beach Museum of Art (Fire Station) Video Annex. We used the programming language called ZGRASS to generate images on a PC running DOS. ZGRASS had been developed by Thomas DeFanti in 1978. It was here that I created my very first computer graphic images. I still have the image or images on a floppy disk, but I have no easy way to access the files.

The situation with Frank was a curious place to be because by then I was quite accomplished using analog media (for painting and drawing) but I had to start all over from ground zero, learning to draw rudimentary forms by typing code on a keyboard and then seeing the result on an attached monitor. It was odd and disorienting but a fascinating experience.

I was excited by this first engagement with new concepts, terminology, and the dynamics of a new medium, a way of making pictures by “talking to a computer” with code; which seemed at the time like a kind of calculating typewriter with a TV screen. I know this probably sounds kind of quaint now.

In Tony Longson’s class it was a similar experience, learning to code simple graphics, but this time on a VAX 11/730, mainframe programming in BASIC.

My biggest take away was that I wasn’t that keen on an algorithmic approach to making 2D pictures. In Youngblood’s Expanded Cinema class, I had been exposed to what advanced digital imaging could produce so that is where I wanted to go. A year later in 1985, I was able to get access to the Cubicomp Picture Maker system that ran on a PC with an attached frame buffer. For its time and platform, it was quite powerful. It supported 3D modeling and animation bundled with a 24-bit color paint system. You could output a sequence of single video frames directly to video tape. This was 6 years before the advent of Quicktime in 1991.

I have to say that both Frank Dietrich and Tony Longson (1948-2021) are legendary pioneering digital artists in their own right, but I didn’t realize it until years later as I learned more about the art form’s history. They were both quite low key about their accomplishments.

Besides producing some very interesting graphic work, Frank Dietrich was an insightful theorist and historian. One of his short essays first published in the LEONARDO Journal is a seminal text in the field.

Tony Longson and I were later in the same circle of colleagues, and we showed work together in several exhibitions including at EZTV’s CyberSpace gallery in 1993. It was wonderful to discover that he had been included in the now historic 1976 book edited by Ruth Leavitt called Artist and Computer.

NYC 1983-85 (1993) © Victor Acevedo

How has your interest in synesthesia and cymatics influenced your time-based works?

Thanks for this question. It’s been gratifying to see that these elements which I feel are conceptually operative or referenced in my digital video work have been of interest. Coincidently, I was asked about this in another interview recently.

Let me begin by first saying my approach to making time-based works comes out of my interest in the genre called ‘visual music’. In 2013, it’s a term I updated to ‘electronic visual music’ to reflect 21st century techniques for generating the motion-graphic components. Over the years, here and there, I see others adopting this updated term as well. The main characteristic or language of visual music is its dynamic representation of sonic elements in visual form.

In my mind this is related to synesthetic phenomena in that visual music operates perceptually with a tight interplay or interchangeability of audio and visual signals. Synesthesia manifests as a kind of cross wiring of the senses, for example when someone hears sounds or reads words and they might perceive them as colors. Sometimes words can evoke tastes.

“These involuntary associations are unique to the individual, consistent, and perceived as vivid and real, though different from normal sensory experiences.” This is from WebMD.

The science of cymatics has also been an influence. I’ve been fascinated by the natural geometric patterns and the dynamic symmetric forms in physical materials such as sand or water that are automatically generated and morphed in real-time by modulations of vibrational sonic frequencies. It is easy to see how these types of patterns lend themselves to the language of visual music. There is something very satisfying about them and for me evoke a kind of psychedelic imagery.

Although the earliest discoveries of cymatic phenomena were documented in the 1600’s, in my lifetime, it was coming across a book by Hans Jenny called Cymatics (volume 2) published in 1974, that really embedded the phenomena into by artistic DNA, if you will. I first considered the forms relevant to my static images, but I realized that they or the phenomena would be most applicable to time-based media. There are several good documentaries about cymatics on YouTube.

Here’s a couple of them.

Watching excerpts of these videos I’m reminded that the phenomena of cymatics is inherently a natural form of visual music.

Your work has been included in major digital art collections, such as the Spalter and Prince archives. How does it feel to see your early explorations now considered part of art history?

To be included in these two major digital art collections along with some of the most important artists in the field, is an incredible honor. It is a great affirmation, getting that kind of recognition. I knew Patric D. Prince (1942-2021) personally from the time I worked with her at the EZTV/CyberSpace gallery. However, I met her before that, originally through the ACM SIGGRAPH community. She was an amazing person, and I learned a lot about the history of the digital art in my conversations with her.

Included in her collection now housed at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, is my physical inkjet print from 1990 called Tell Me the Truth. This is an example of a piece I created using the aforementioned Cubicomp Picture Maker system. In September 2023 Tell Me the Truth, as a digital file, was listed on the Ethereum blockchain (this was in an edition set of 36) through the gallery called Expanded Art in Berlin. For anyone interested, at the moment, there is one those now available on OpenSea.

Tell Me the Truth (1990) © Victor Acevedo

Anne and Michael are visionary art collectors. Anne is also a wonderful digital and multi-media artist in her own right. She was an early proponent of the blockchain marketplace. Quoting from their website: “The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection is one of the world’s largest private collections of early computer art, comprising works from the second half of the twentieth century to present day.”

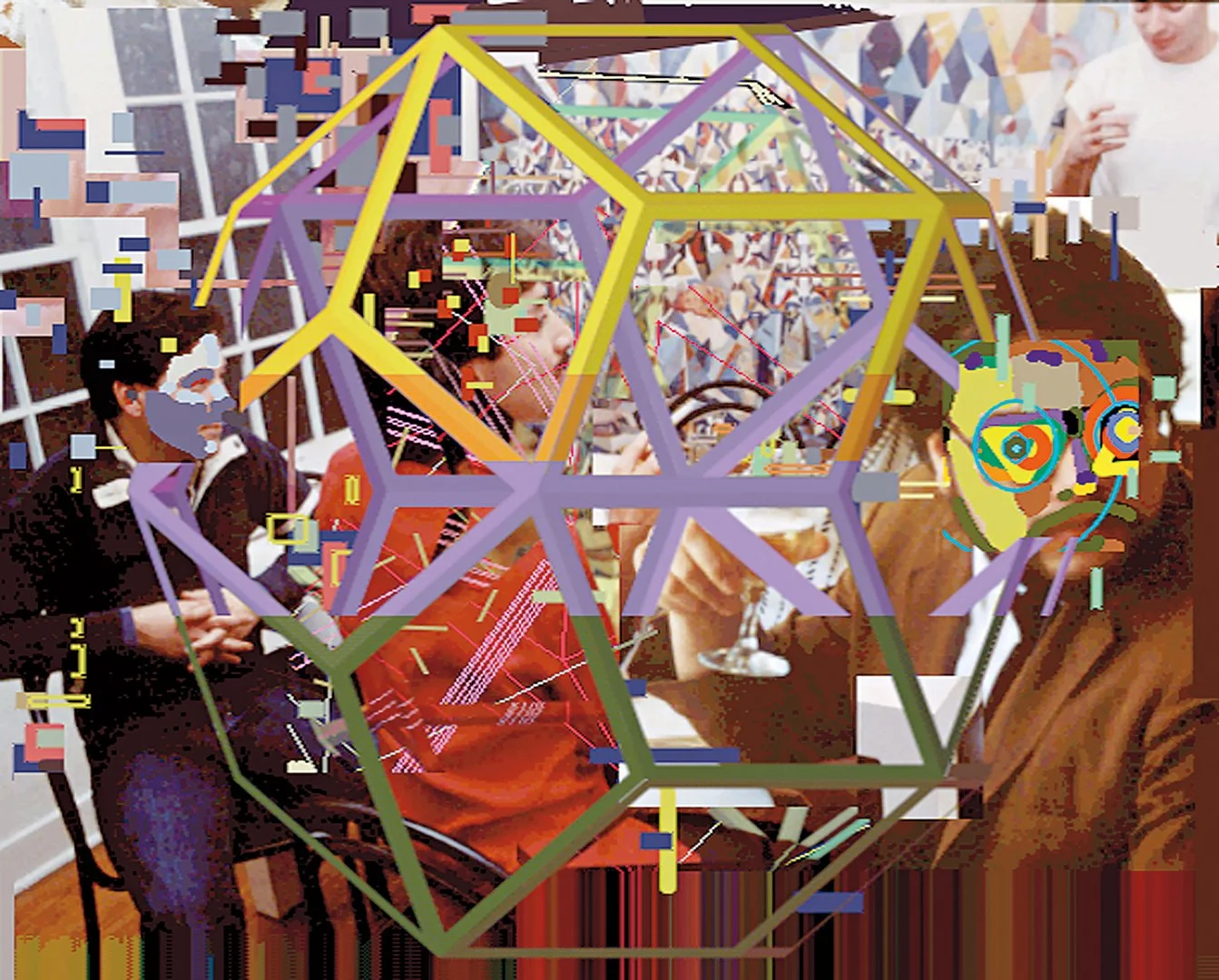

Three of my print works are included in their collection. They are Sunburst Couple v03 (1998), The Violist (1996), and NYC 1983-85 (1993).

Sunburst Couple v3.1 (1998) © Victor Acevedo

You taught for over a decade at the School of Visual Arts. What ideas did you most hope to pass on to younger artists just discovering digital tools?

From the perspective of a fine art practice, I encouraged them to find their unique artistic voice. Via exploration and experiment, to find their personal path. Take on commercial work that is fulfilling but try to leave space and time for your personal work. Thinking back, my undergrad and graduate students from the period 1997-2008 had usually already discovered digital tools before they got to me. So, the task at hand was to learn to use them in a sophisticated and innovative way to earn a good living.

I don’t recall using these exact words then, but I would encourage my students to maintain a life balance (in mind, body, spirit) for longevity and self-actualization.

February 29, 1993 v02 © Victor Acevedo

Looking back, what was the biggest challenge you faced as a digital artist in the 80s and 90s — and do you see echoes of those challenges today?

In those days the fine art market was not ready for digital art even though it had been around since the 1960s. The idea that it was collectible was not the prevailing view, at the risk of understatement.

After all these years, that’s finally beginning to change. But interestingly it’s been the emergence of a sales platform native to the digital domain that has opened things up. I’m referring here to crypto currency, the blockchain, and web3. And of course it’s generational; young people are now moving into positions of cultural power, and they grew up with computers. This technology is a natural part of making or understanding the art of our time.

The controversy around or resistance to AI being used to make art feels quite similar to the resistance to using computers to make art, back in the day. But in someways it’s much more intense because the stakes are much higher now, given the state of our planet and our relationship to it, and the awesome power and potential of machine learning. AI’s possible effect on culture and how humans will survive are critical issues. That’s why in my opinion we must emphasize the use of AI “for good.”

X Hour (1994) © Victor Acevedo

What is a profound childhood memory?

Here’s a few: Drawing spontaneously at the age of 4. Drawing on a large green chalk board for seemingly hours with my older brother David, when I was about 5 or 6. My father teaching me two-point perspective at age 9.

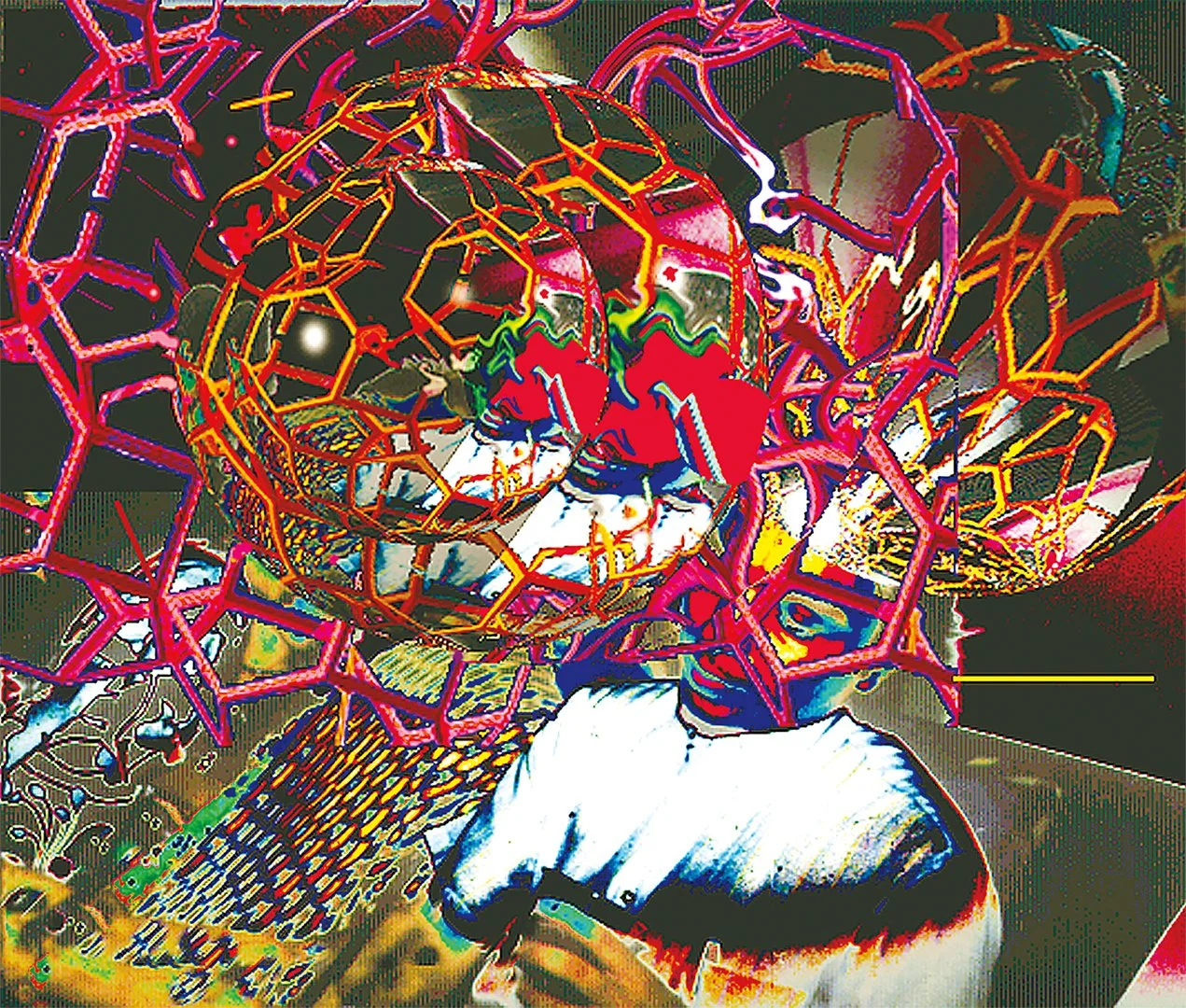

Still image from the EVM work Highway Bridge (2024) © Victor Acevedo

What is a fun fact about you?

Here is something that I don’t publicize so much but when you say ‘fun fact’ in the context of this interview, I thought of this immediately. It was that time I met Salvador Dali, in his hometown of Figueras, Spain in July 1977. I was 23 years old on a family holiday and being a young art student of that era, he was a major influence. He would have been 73 years old.

I remember coming across a reproduction of his painting Persistence of Memory when I was about 10. It made a deep impression. In a sense it became part of my artist DNA manifesting years later when I was developing my own style.

I was awestruck, because he was a hero of mine, and I didn’t expect to meet him. It was one those chance occurrences that lasted only a few minutes but left a lasting psychic imprint, in good way. It just seemed like fate. I shook his hand which was very limp. It reminded me of my grandmother’s! I happened to have my sketch book on hand, and I showed him a drawing that I had been working on. He stared at it with an unflagging intensity for about what seemed like 5 or 10 seconds. For the rest of the day, I was in a euphoric state, almost like a pleasant drug experience.

After seeing the drawing, Dalí said only two words, "Cadaqués, Saturday." He seemed to be inviting me or us to his current home in the nearby town of Cadaqués. So, the next day we turned up, but he wasn’t home or if he was, he didn’t answer the door. But that was ok. The connection had been made.

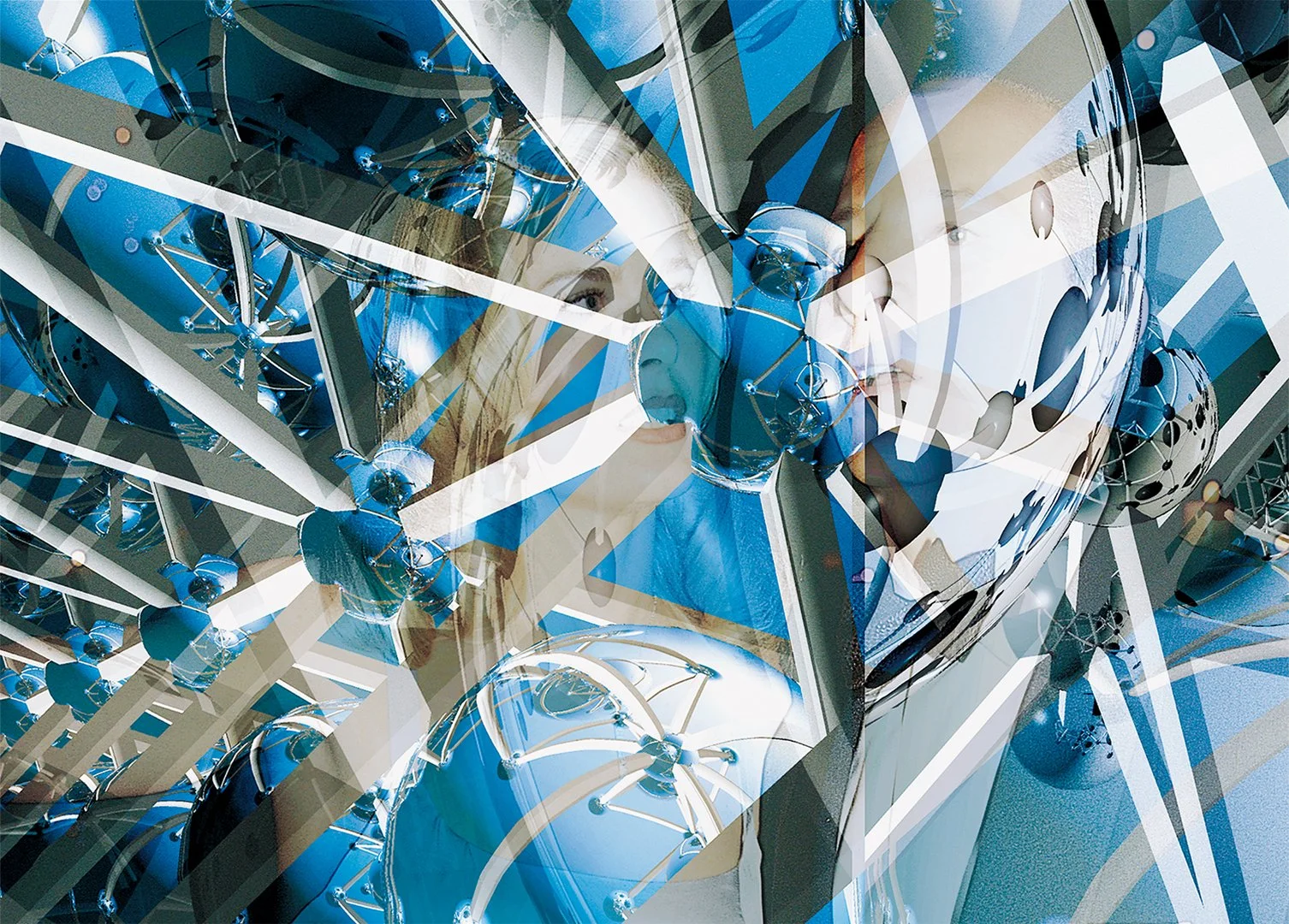

Blue Matrix Interlock (Anonymous Ambience vs11) (2025) © Victor Acevedo

Life Form v03 (Recordings 2017) © Victor Acevedo