Michele Rinaldi on AI, Ecology, and the Art of Responsible Technology

By Cansu Waldron

Michele Rinaldi is a Rome-based artist and researcher working at the intersection of new media, digital arts, and environmental sustainability. His practice centers on multimedia installations powered by artificial intelligence, exploring invisible ecological processes such as CO₂ emissions and environmental transformations linked to climate change. Through his work, Michele investigates how technology can both reveal and critically reflect on the relationships between humans, nature, and computational infrastructures.

After graduating with honors in Fine Arts from the “Sacro Cuore” Art High School in Cerignola, Michele earned a Bachelor’s degree in New Technologies of Art from the Academy of Fine Arts in Foggia and a Master’s from the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, both with top marks. Currently a PhD candidate in Innovation, Technologies, and New Materials for Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, he develops AI-driven projects with attention to energy efficiency and sustainability. Michele has exhibited internationally at AI WEEK in Milan, Data/Humans in Bahrain, and The Wrong Biennale in Copenhagen, and has published in Prompt Magazine and The AI Art Magazine. His work blends technological rigor with ecological consciousness, creating immersive experiences that invite audiences to rethink their impact on the environment.

We asked Michele about his art, creative process, and inspirations.

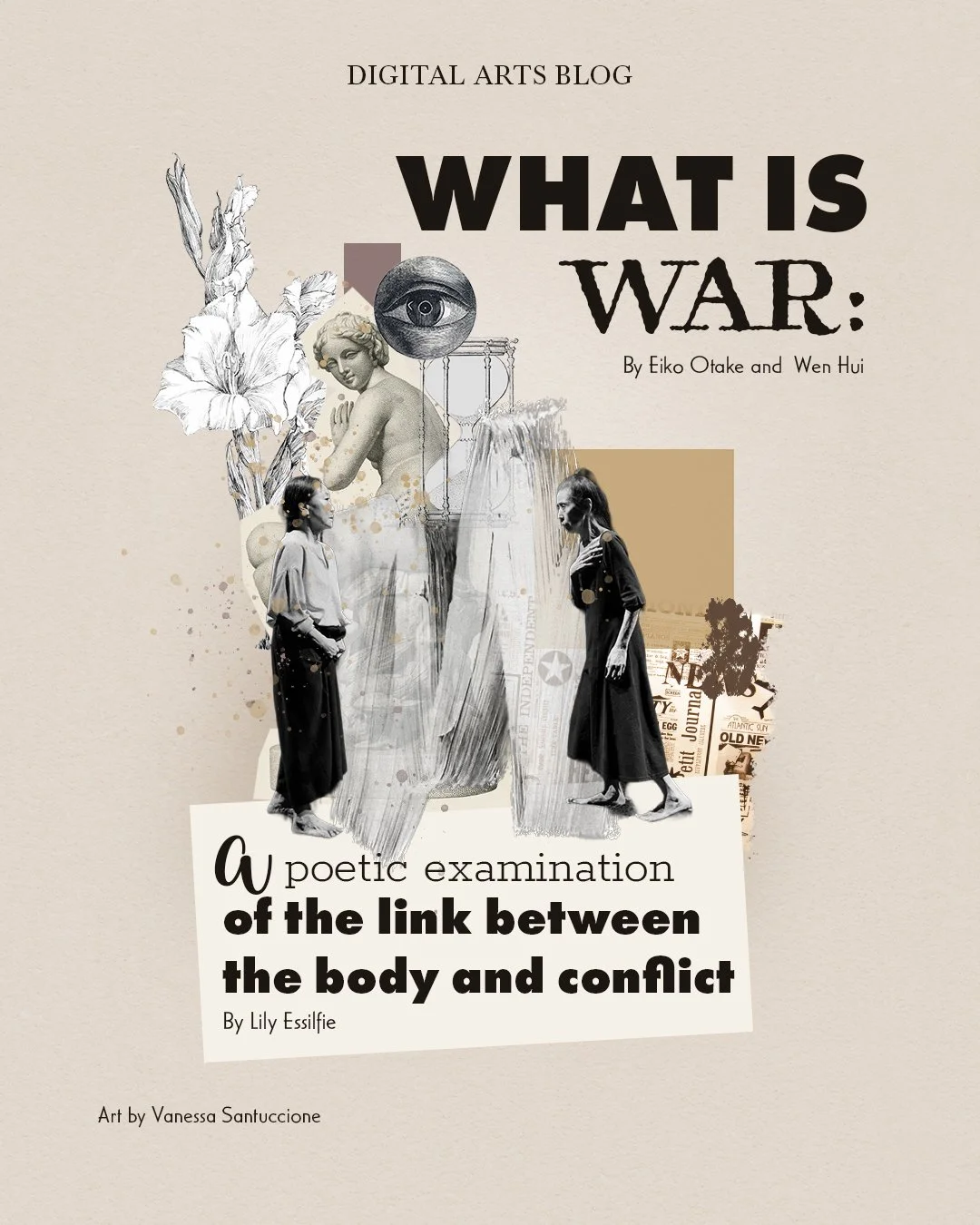

Xylella Latente

Your work uses AI to reveal “invisible ecological processes.” How did you first become interested in connecting artificial intelligence with the environment?

It was a very spontaneous and natural process that developed over the years. When I first started experimenting with early AI models, I immediately encountered the technical limits of my computer: training a model required enormous resources. This led me to use cloud infrastructures and, consequently, to wonder which GPUs were being used and how much energy the whole process actually consumed. From there, a deeper awareness emerged: technology cannot be separated from the environment. I have always been fascinated by the relationship between innovation and sustainability, two dimensions I consider inseparable. McLuhan describes the medium as an extension of our senses and mind, while Parikka interprets it as an extension of the Earth. I find both views true: technology is simultaneously a human prosthesis and an ecological fragment. It is paradoxical to think that neural networks, although inspired by the human brain, are still infinitely less efficient than our biological system.

Xylella Latente

You design your own machine learning models — that’s quite rare among artists. What draws you to that technical side of creation, and how do you balance it with the poetic or conceptual side of art?

I have been studying new media art in depth for at least five years. One aspect I find truly fascinating is the ability of artists to subvert technologies, pushing them to do things they were not designed to do. In our society, technology is often presented as a closed box, where we can only press a button without knowing what’s inside or how it works. The great merit of new media art pioneers has been the courage to open that box, explore it, and, most importantly, play with it. Seeing technology do something it wasn’t programmed to do is, in my view, a form of research: a way to produce knowledge and tackle complex themes playfully, simply, and lightly.

For my part, I began to engage with AI because I was afraid of it. I wanted to understand what lay behind these algorithms: using a pre-existing model to generate images was not enough; I wanted control over the entire process. What fascinates me about using autonomous systems is the interaction that arises with them. I discovered that even when “autonomous,” every AI carries the imprint of its creator. In this sense, each model becomes a sort of alter ego, reflecting aspects of oneself, including biases that often remain invisible in a normal artistic process.

This dialogue with the machine also has an aesthetic dimension: the beauty of using a generative system is exploring the latent space, which has infinite dimensions. Navigating it is like exploring oneself: sometimes you realize you need to change direction, other times you feel compelled to continue along the path you’ve taken. Technique, for me, is only a tool to move through this great mirror that is the machine, traveling among the infinite reflections of oneself.

Sustainability runs through your practice, not only as a subject but also as a method. What does a “sustainable computational system” look like in practice?

AI is a complex infrastructure made up of many components. Often these are controlled by Big Tech, and we artists do not have direct access to the systems that support them. AI appears as something invisible, and the big challenge for me is to enter this technology using a kind of hacker-artist approach. If I cannot build my own solar-powered data center, I can still act consciously: for example, by choosing the most efficient data centers in the world and connecting only to them when training my models. Or by intervening in the code, lightening the computational load, optimizing learning processes, and ensuring the model stores only what is essential, eliminating the superfluous.

I enjoy programming my own AI, even though I am self-taught. Today, there is growing attention in computer engineering to move beyond a purely commercial logic of “model efficiency” and embrace a mindset more conscious of energy consumption and environmental impact. Disciplines such as Green AI and Edge Computing address the sustainability of computational systems. Generally, interventions happen on two levels: hardware infrastructure and software architecture, metaphorically representing the body and mind of the machine. The first focuses on improving data center efficiency, while the second aims to optimize code and reduce resource consumption. As an artist, I cannot directly change these technical aspects, but I can understand their principles and integrate them into my creative process, making my practice more conscious and sustainable.

Xylella Latente

Many of your works rely on datasets you build yourself. What kinds of images or data do you collect, and how do you approach the ethics of using them?

I create my own datasets for both aesthetic and ethical reasons. Aesthetically, they allow me to obtain exactly the output I want. Ethically, many large datasets historically built for AI come from questionable practices: they scrape images online without respecting copyright and rely on underpaid labor for labeling. By creating my own datasets, I strive to use images I have taken myself or sourced legally online. Data is the raw material of the creative process: if it isn’t ethical from the start, the final result cannot be ethical either. Whatever the data format, images, videos, or numbers, I always ensure it respects the work and rights of others.

Let’s talk about The AI Chronotopes: Moons, Castles, Trees! Can you tell us about your piece in the exhibition? What questions are you hoping to raise through it?

Latent Xylella is the result of a long and deep project, tied closely to my origins. I was born and raised in Puglia, a region famous for olive oil and millennial olive groves. Over the last ten years, this landscape, along with the local economy and social life, has been profoundly threatened by a bacterium called Xylella fastidiosa, a pathogen that infects plants and compromises their survival.

I believe Xylella is one of the clearest examples of how humans cannot live apart from nature. In an era marked by the Anthropocene, ignoring the environment and failing to care for it is no longer an option. Timothy Morton describes climate change as a “hyperobject,” something with many dimensions and often invisible aspects. Latent Xylella is my humble attempt to give form and aesthetic to a hyperobject like the devastation caused by Xylella: a phenomenon affecting millennial olive groves, thousands of people, cultural heritage, the economy, and regional traditions.

Xylella Latente

The discussion around AI and energy use is becoming urgent. How do you think artists can lead by example in creating responsibly with technology?

Joanna Zylinska compares AI-generated art to Candy Crush because, in many cases, artists seek algorithmic wonder rather than conceptual or critical engagement. Often, AI-driven creation becomes mechanical, endlessly generating images until something visually striking emerges. Using AI this way is anti-creative.

Artists, more than anyone, must be aware and critical of the tools they use. As Spider-Man says, “With great power comes great responsibility”: approaching AI is not like using a simple tool. From both ecological and creative perspectives, a pencil has a completely different impact compared to AI. With a pencil, you can create masterpieces; with AI, you can generate almost anything, but this carries great responsibility and potential risks.

Great artists teach us to understand the zeitgeist, to observe the world critically. Creativity comes from asking questions, not providing ready answers. Using AI compulsively to get answers can impoverish our thinking and conceptual capacity. To create responsibly, we must reflect on both the tool’s energy impact and our creative role in the process.

Dendroclock

What else fills your time when you’re not creating art?

I’m 25 years old and still feel quite immature and inexperienced. I spend much of my time learning and studying, as I am deeply curious about the world. Today’s society often wants instant results: if we’re hungry, we open the fridge and find ready-to-eat food. In this way, we lose touch with the real world and its rhythms.

Much of my time is dedicated to learning to live. I am passionate about hands-on activities that respect natural rhythms. Recently, I’ve been learning to garden and cook: simple acts that teach patience and care. They teach what it means to nurture a plant, wait for a seed to sprout, and anticipate the harvest. I love technology, but we often use it only to free up time, then don’t know how to fill it; we no longer know how to be bored. Technology is incredibly powerful and can help us build the life we want. Today, we can learn virtually anything online, so why not use it to master activities that teach patience and effort instead of indulging every desire instantly?

You’re currently pursuing a PhD exploring innovation and new materials for the arts. How do you see the next generation of artists approaching digital sustainability differently than today?

Art has many examples of technological sustainability, take projects like Solar Protocol. I am particularly inspired by net artists, who revealed dynamics of the internet that only now many people begin to understand. Today, the internet has changed drastically from the free space of the ’90s. It has become an environment colonized by a capitalist mentality, increasingly profit-driven and extractive.

We need to learn to look inside things, into the devices that permeate every aspect of our lives. If we don’t, in a few years, when these devices enter our bodies, it might be too late. The metaphor of the “cloud” is an illusion. Internet is not “somewhere in the sky”: it resides in data centers, submarine cables, and the exploitation of human and environmental resources. Artists like Trevor Paglen and James Bridle have made this very clear. Every image, message, or email we send is not immaterial, this is a major illusion.

My generation is very sensitive to these issues, which is a huge advantage: for us, sustainability is not just a theme but a matter of life and death. We can learn from great artists and make courageous, coherent choices. Personally, this year I declined several overseas conferences to avoid polluting with flights, traveling only when truly necessary, even at the cost of significant opportunities. In an era of influencers, where everyone speaks and few listen, it is important to remain silent and let our actions speak, without proving anything to anyone. Art, for me, is an extraordinary way to do exactly that.

Xylella Latente