From Concrete Poetry to Digital Constructivism: Inside Robert Richardson’s Practice

By Cansu Waldron

Robert Richardson is a UK-based visual artist and writer whose practice moves fluidly between concrete poetry, constructivist abstraction, and digital image-making. Originally trained in Communication Design before later studying Education, he spent many years as a university lecturer before shifting his focus to independent creative work. He now produces artworks across media, with solo exhibitions in the UK, Germany, and Portugal, and his graphic art held in major collections including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Gallery Library and Archive, and the National Gallery of Australia.

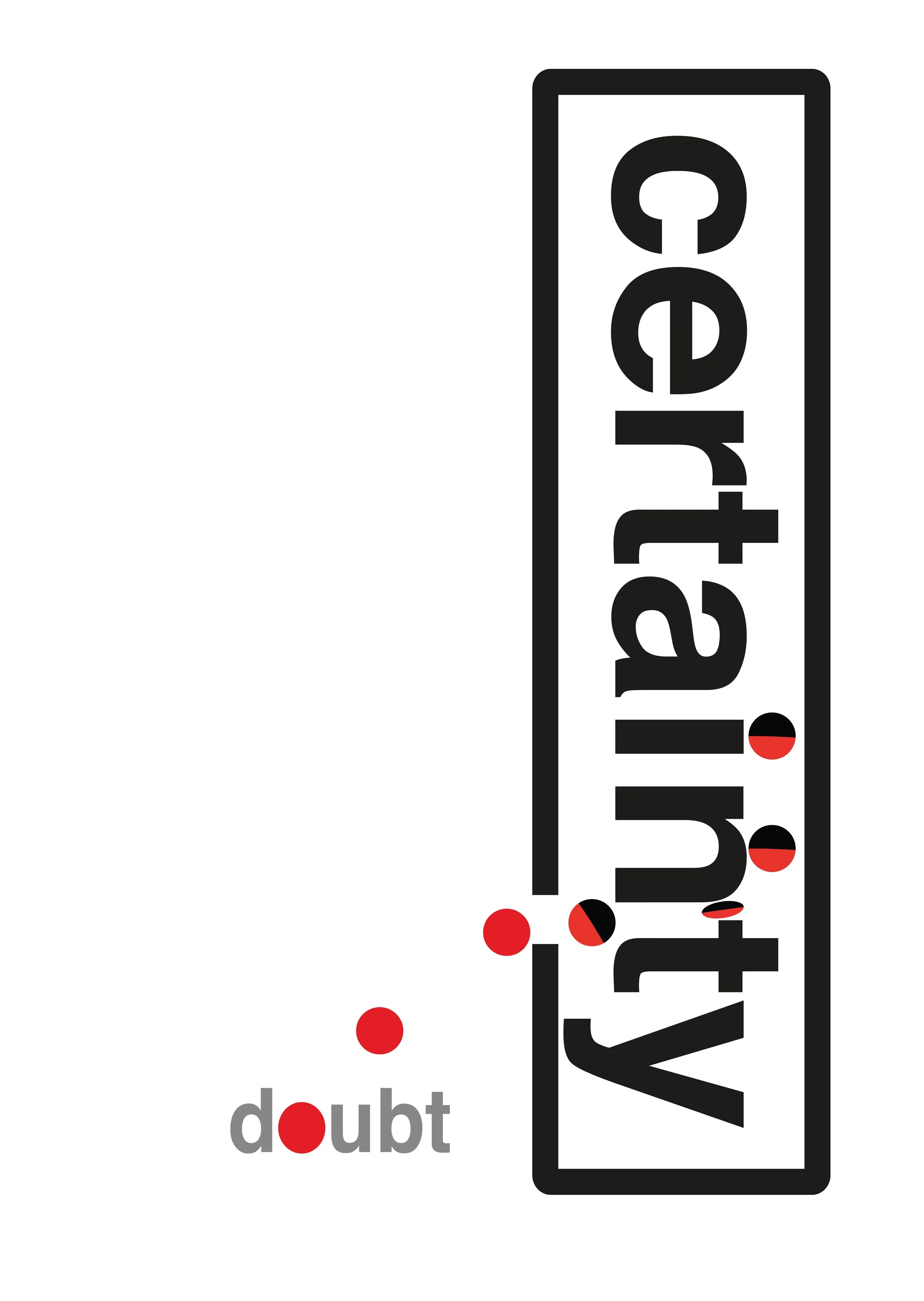

Robert’s work is deeply informed by language, structure, and the history of abstract art. His early involvement with concrete poetry led to a pivotal solo exhibition in 2014 at the gallery of Eugen Gomringer, the “father of concrete poetry.” Reworking earlier poems through digital tools opened up a new direction in his practice, prompting him to experiment with vector software, minimalist geometry, and constructivist forms. Since then, he has continued to explore how digital technology can serve as a truly expressive medium — one that still allows intuition and spontaneity to play a central role.

Today, his portfolio spans limited-edition prints, phone-and-tablet drawings, abstract animations, and ongoing self-portrait series. Whether working with mouse, stylus, or finger, Robert is interested in how artworks emerge through process — in the small aesthetic decisions, experiments, and moments of chance that make each piece difficult to recreate. His practice sits at the intersection of poetry, design, and digital image-making, embracing both precision and play in equal measure.

We asked Robert about his art, creative process, and inspirations.

Can you tell us about your background as a digital artist? How did you get started in this field?

In 2011, I met Eugen Gomringer, known as the “father of concrete poetry,” on his visit to the UK. He saw some of my concrete poems/text art and invited me to have a solo exhibition at his gallery in Rehau, Germany, and this took place in 2014. I selected the best of my concrete poems and reproduced them as large format exhibition prints using Adobe Illustrator (i.e. vector software). I did not have quite enough pieces, so I created some non-text visual art using Illustrator (since the gallery also focused on Constructivist art), and this set me on the course of producing an ongoing series of abstract digital artworks.

What inspires your art? Are there any particular themes or subjects that you enjoy exploring through your artwork?

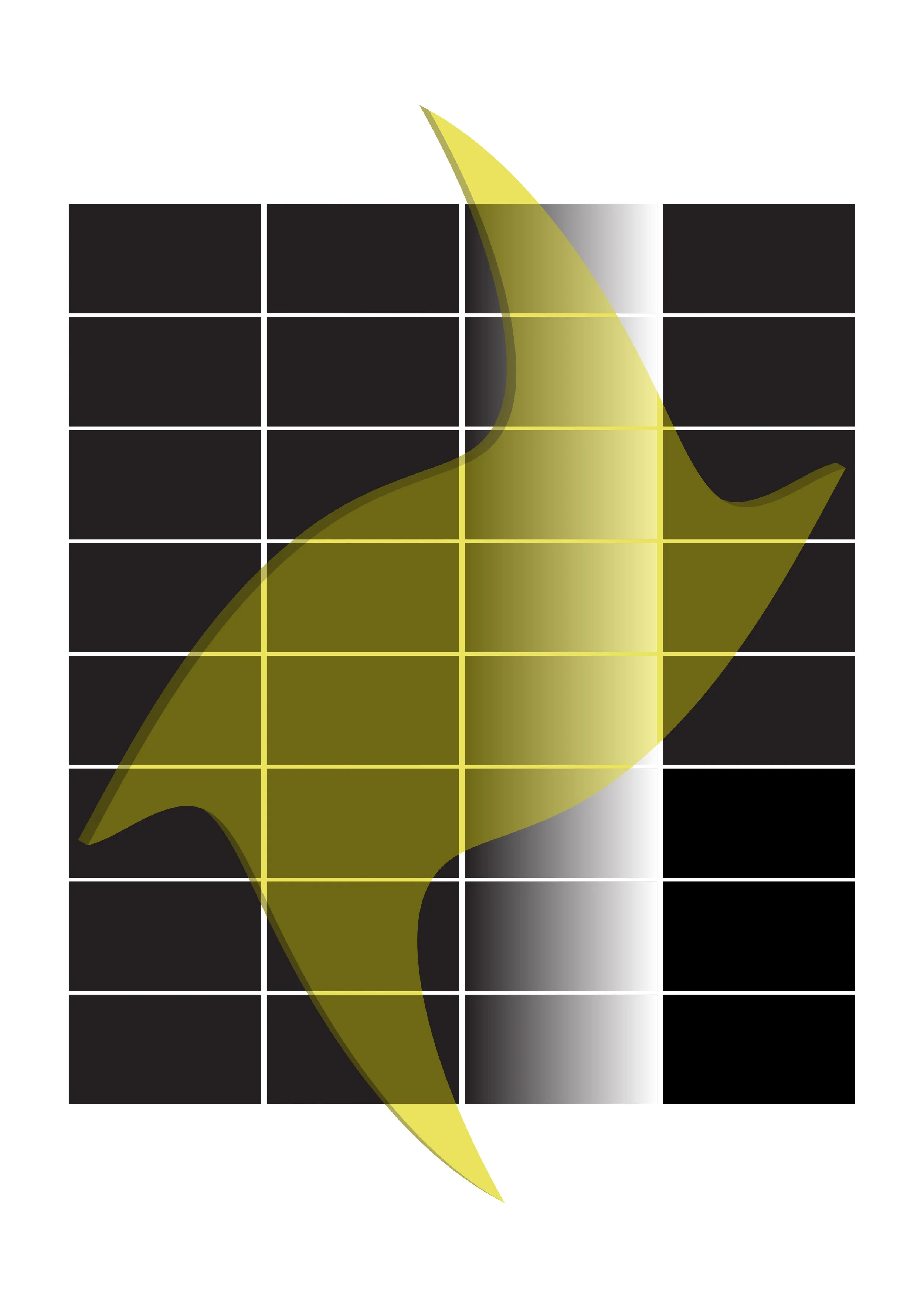

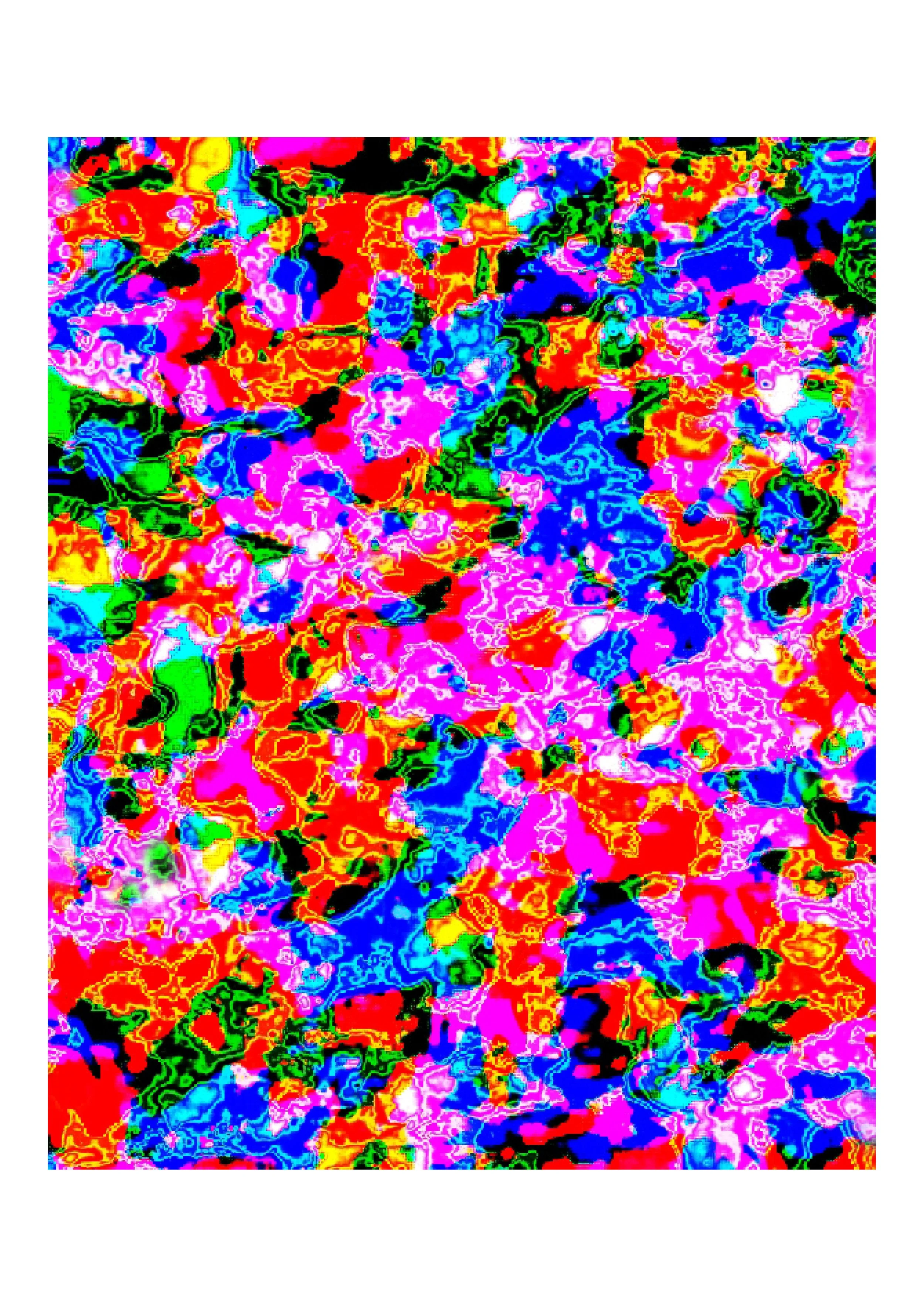

At art school, I was influenced by the Bauhaus and Constructivism, and this has continued. My Constructive Art series, twenty of which have recently been exhibited in a permanent virtual gallery at The Vilbil: Online Hub for Art and Artists, shows this influence. It is work produced using vector software. I also have artworks created with pixel-based apps, and this tends to be more intuitive and stylistically anarchic, relating more to Abstract Expressionism. I’m old enough to have experienced hippie lightshows, and the enduring vision of psychedelia is in the mix as well.

You originally studied communication design and later education. How have these two strands shaped the way you think about art today?

Studying communication design has led me to work across various media: typography/text art/concrete poetry; graphics; photography; video; installations. Having that range and freedom was important to me then and still is now. Also, my work in concrete poetry is very graphic and coherent, which comes from this design background. The same might be said of my Constructive Art series (though fine art influences are also present: Concrete Art and Minimal Art supplementing Constructivism).

With education, I took a teacher training course for further education (in the U.S. the equivalent would be community colleges) and then taught at a college in the north of England. To begin with I was teaching on courses for the young unemployed, but towards the end I led a pre-university media course at the art school part of the college. During this time, I continued studying education part time and completed a Master’s, and after ten years switched to teaching at a university, becoming a principal lecturer in communication at a faculty of humanities. My main job involved initiatives in academic guidance (helping first degree students improve their essay writing and other academic presentations).

In addition, for many years I led a visual communication module, which provided humanities students (in subjects such as literature, history, politics etc) with an opportunity to engage with texts and images in terms of design. We worked together in an Apple Macs suite. Some students came with existing Photoshop skills and I introduced everyone to Illustrator. This reinforced my own Illustrator skills as a foundation for the digital fine art I have pursued since retiring from teaching.

I must also say that in the 90s I began exhibiting quite a lot: at this time it was mainly art installations with a strong conceptual basis, and my bosses at the university were always supportive, even though I was working in a humanities faculty.

You describe being “inside a process of aesthetic judgments and experiment.” Can you talk us through what that process feels like from the inside?

This mainly applies when I am creating art using pixel-based apps, which, as mentioned, allow more intuitive approaches. The “inside” of this is usually a concentration of many decisions: a flow of visual experiments and decision making, accepted or rejected according to aesthetic choices. In this flow the decisions can be very small adjustments, but of course in art every adjustment is crucial. The results are often complex abstract images. Afterwards, I realise it would be difficult, near impossible, for me to reproduce the artwork: I take this as a good sign, that I have indeed been inside a process unique to a particular piece.

When you recreated earlier concrete poetry works digitally, did the process change how you thought about those pieces?

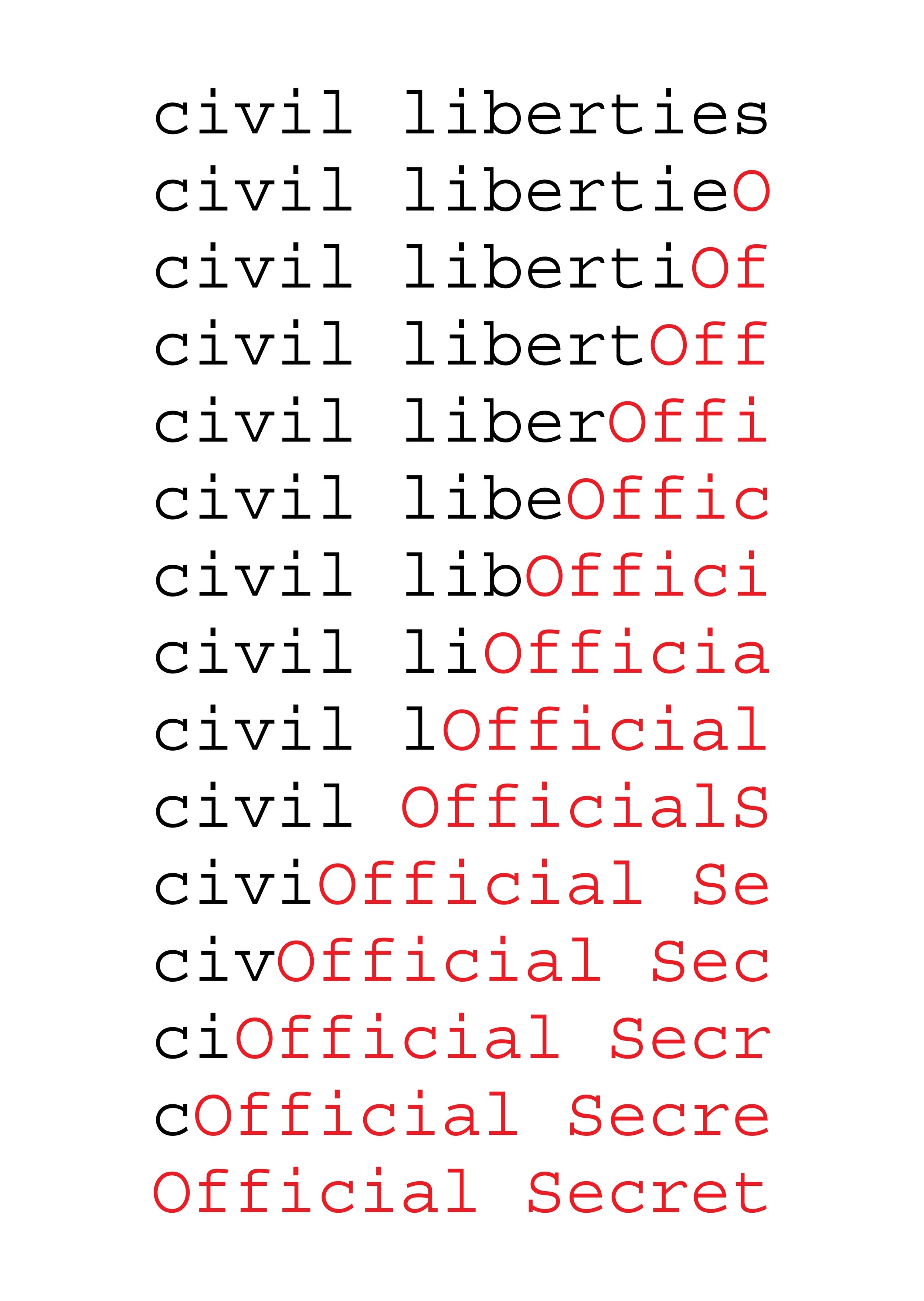

My concrete poem civil liberties/Official Secret, which in the 1980s was on sale as a postcard at bookshops throughout Britain, has always included red type as well as black (and depends on colour to help convey its meaning). Typically, though, concrete poems have been black on white. When I was preparing the poems for exhibiting in Germany, and using Illustrator, I added touches of colour to some, when I thought it appropriate.

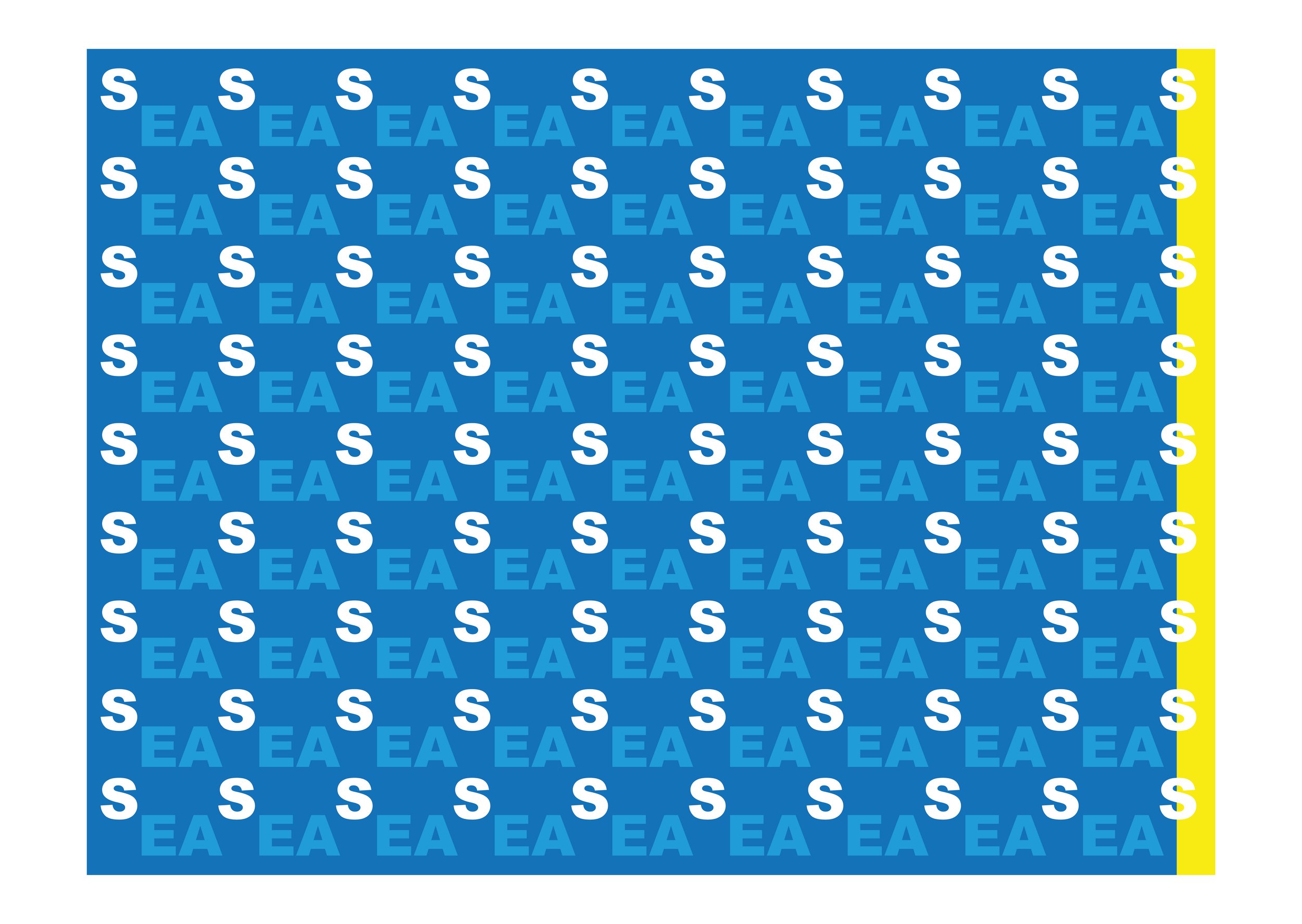

With SEA, for instance, I used two different blues and white for the ‘S’ that represents the foam of waves. Later I added a yellow strip for a beach. I think this gives more definition and liveliness to a fundamentally minimalist concept. With my digital realisations, I made the poems larger than ever before: my exhibition prints were A1 size. The ethos of concrete poetry includes not having definitive formats and being affordable. Recently, I have achieved this through linking up with Printumo, a print-on-demand company, and having my concrete poems on sale at AvenueBob, my own online store.

What keeps you curious as an artist after such a long and varied career?

I like the word ‘curious’, and the dimension of play is important in the concrete poetry and Fluxus area of the avant-garde. It’s always good to remain open and try new things. In 2020, I started working with abstract animations, which require an additional set of time-based decisions (some of these moving image artworks are available for streaming from the Paris-based Artpoint company).

Art interrogates perceptions and consciousness, and it doesn’t seem they are ever exhausted. The examples of others remain a help to me. I’ve been fortunate to know three remarkable people: Henri Chopin, the great sound and typewriter poet; Eugen Gomringer, who was of foundational importance to concrete poetry; and Nicholas Zurbrugg, a university colleague and friend: a key writer on concrete poetry and intermedia art, and an organiser of incredible events.

If you could go back and talk to your younger self in art school, what would you tell him about the future of digital art?

I would say that computers would arrive on desktops (and with laptops, tablets and phones, places beyond that), allowing individuals autonomy over amazing digital forms of communication and expression, and although coding is to be respected, digital tools will provide a great accessibility. Specifically on art, digitally revisiting a movement like Constructivism means it can be realised and further developed in ways close to the optimum. I know there are valid reasons for paint and canvas to continue, but there are 21st century digital voices saying, “move over, we’re coming through.”

What is a fun fact about you?

I was once involved in avant-garde events at an upstairs room of The Enterprise pub, Chalk Farm, London. At the time, I had a long hippie beard, a magnet for abuse from the increasing number of punks, so I cut and shaved it off at one of these events. This was recorded on video by some students from Wimbledon School of Art. Does that video still exist?

What else fills your time when you’re not creating art?

I follow football (that’s soccer, not those people wearing helmets and shoulder pads), and support Derby County, and the men’s and women’s England teams.

Robert Richardson’s Links: