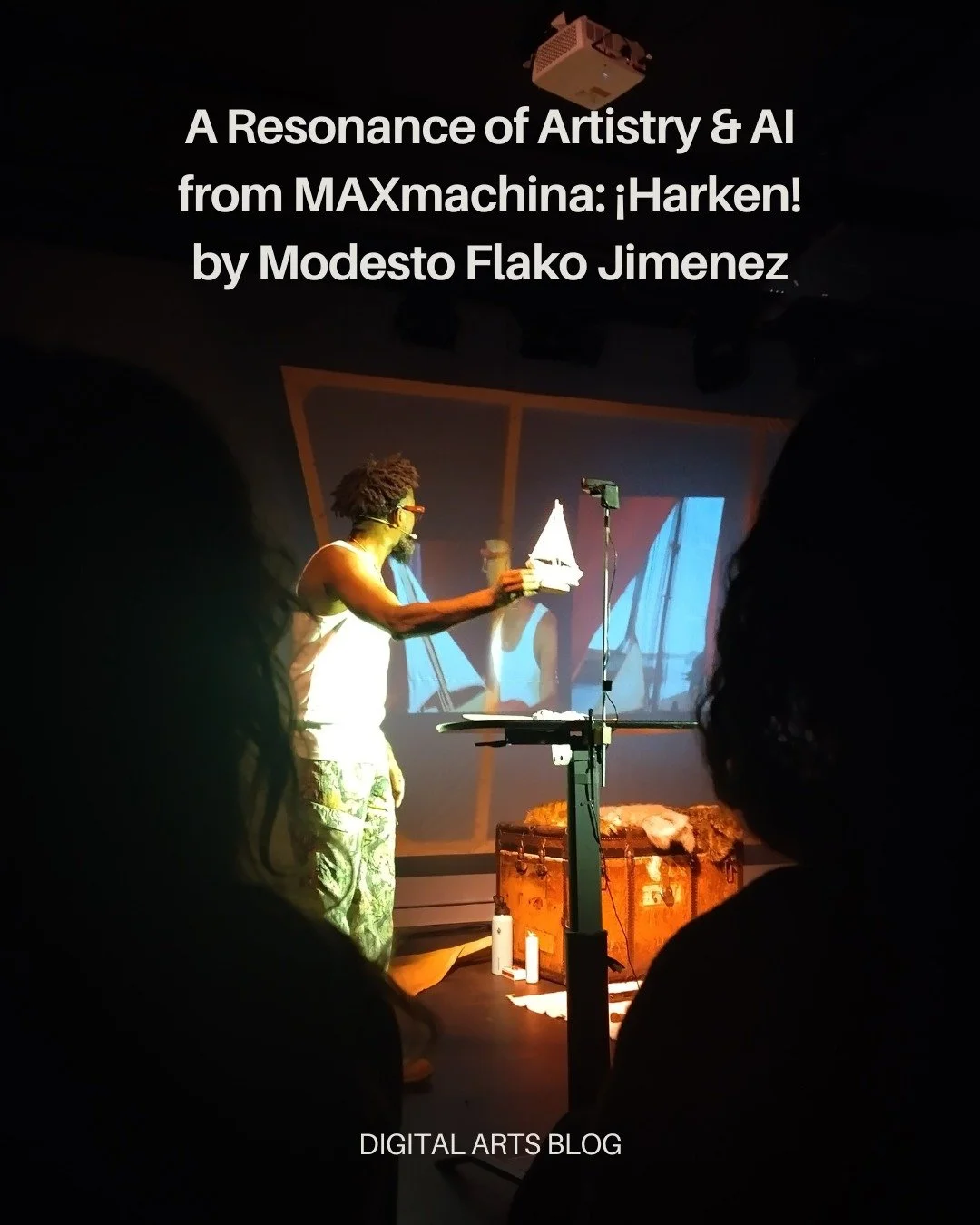

What Goes Into a Collaborative Digital Art Project: Making Our Miracles

It’s been three months since we launched Making Our Miracles, a virtual art exhibition in which people from around the world shared their miracle stories, and a cohort of digital artists depicted these extraordinary events using AI-assisted tools. During the final weeks of the show, we found ourselves reflecting on the experience — from its initiation to the public reaction.

As part of The Wrong Biennale, the exhibition is on view through March 31. Making Our Miracles can be experienced online, with the full exhibition catalog available for download.

Reflections by Lead Artist Clayton Campbell

My initial essay for our project proposed several potential outcomes. They were “making the ineffable knowable, fostering connection and understanding, and celebrating human ingenuity.” After a year of working on Making Our Miracles, I am contemplating several things. First, that the miraculous is expressed through art as revelation rather than representation. Second, that consciousness of transformation originates with feeling, not through thinking. And third, how did AI visual applications assist in arriving at the outcomes I proposed?

The artwork in Making Our Miracles came into being with the collaboration of the storytellers, as their heartfelt narratives are foundational for the project. An emotional connection to the stories became important for our cohort of artists. Stacy Ant said, “I loved all the miracle stories. I have personally experienced moments like that in my life, and I was so excited to bring these moments to life with my artwork- very moving experience.” cari ann shim sham* shared that, “Each prompt mirrored lived moments — small encounters with nature, awe, synchronicity — especially during periods of isolation ……...” Jason Scuderi (lasergunfactory) expressed, “Many of the stories reflected how brief moments can permanently alter one’s perspective. That idea resonates on a personal level—we all carry moments like that—so the process became both introspective and outward-looking.” The artists found a connection to their stories and then used various digital applications to arrive at unique, original works of art.

Our project was exhibited in 2025-26 The Wrong Biennale, whose theme was the use of AI applications. Digital Arts Blog has defined digital art as a large and evolving ecosystem. Until Making Our Miracles, my practice concentrated on digital photography and collage.

The project gave me the opportunity to experiment with new AI applications. My artist toolbox filled up as I worked with photoshop and its expanding menu of generative fill tools. For the first time I used Midjourney AI along with Adobe Firefly, Glitchshop, Topaz Gigapixel, and Recraft AI. I made my first AI videos with KreaAI and DeepAI. Several of my finished images were developed entirely using AI, a first for me. Participation in Making Our Miracles expanded my practice as I learned what AI’s potential could be.

Finding a personal connection with each story was always the starting point. I tried to work from the basis of meaningful personal memories. Some were painful, some wonderful, some were transformative experiences. Feeling them again gave me the confidence to proceed with a degree of connection and respect to the stories. If a picture didn’t feel quite right, I’d return to the story, consider it again, and start the image over. In this sense the storytellers were true collaborators in the creative process.

Two stories that I developed for the project are good examples of my process, starting from a place of feeling and then thinking about using AI to get me to a satisfactory visual response. The first story was about a young man coming out as LGBTQ+. It was gentle; his first loving relationship. Yet it is a universal story, something that anyone can understand who has felt unloved and then been loved, felt its poignancy, and the beauty of it.

“I was 15. I grew up in a family where feelings were not discussed and there was not really any touching, hugging or expressions of love. As a gay boy, on Saturdays I would travel into the city and go to a park where I understood gay men would go to connect. After many Saturdays, I met a very handsome man who invited me to his apartment. He embraced me, held me and kissed me deeply. It went on from there and I felt enveloped in the love of an older man. It was something I had waited for all my young life. The relationship lasted as described for a year, the best year of my life. It was a miracle.”

For the story I made two artworks, a digital photocollage and an AI generated video. Both show a young man and an older man meeting discreetly in a city park. In the background, the myth of Ganymede is alluded to. We see Zeus coming to earth as an eagle and carrying off the beautiful young Ganymede he has fallen in love with. This takes place in a park where the police are scouting a gay man who is cruising. Our couple stands in the foreground. The accompanying AI generated video puts the couple into motion, as the young man and older man meet in a sun dappled scene, coming together and touching each other for a moment. The video loops, the couple endlessly coming together and drawing apart. Yet throughout the couple is in silhouette, their faces covered, perhaps out of fear of discovery for this forbidden tryst.

Underneath these artworks are my experiences and memories living in a homophobic society, seeing how it has impacted my friends, living through the AIDS pandemic as colleagues died, and watching now how around the world discrimination is rising again towards LGBTQ+ communities. And there are also my memories of being unloved, and loved, and the intensity of feelings that I still carry all these years.

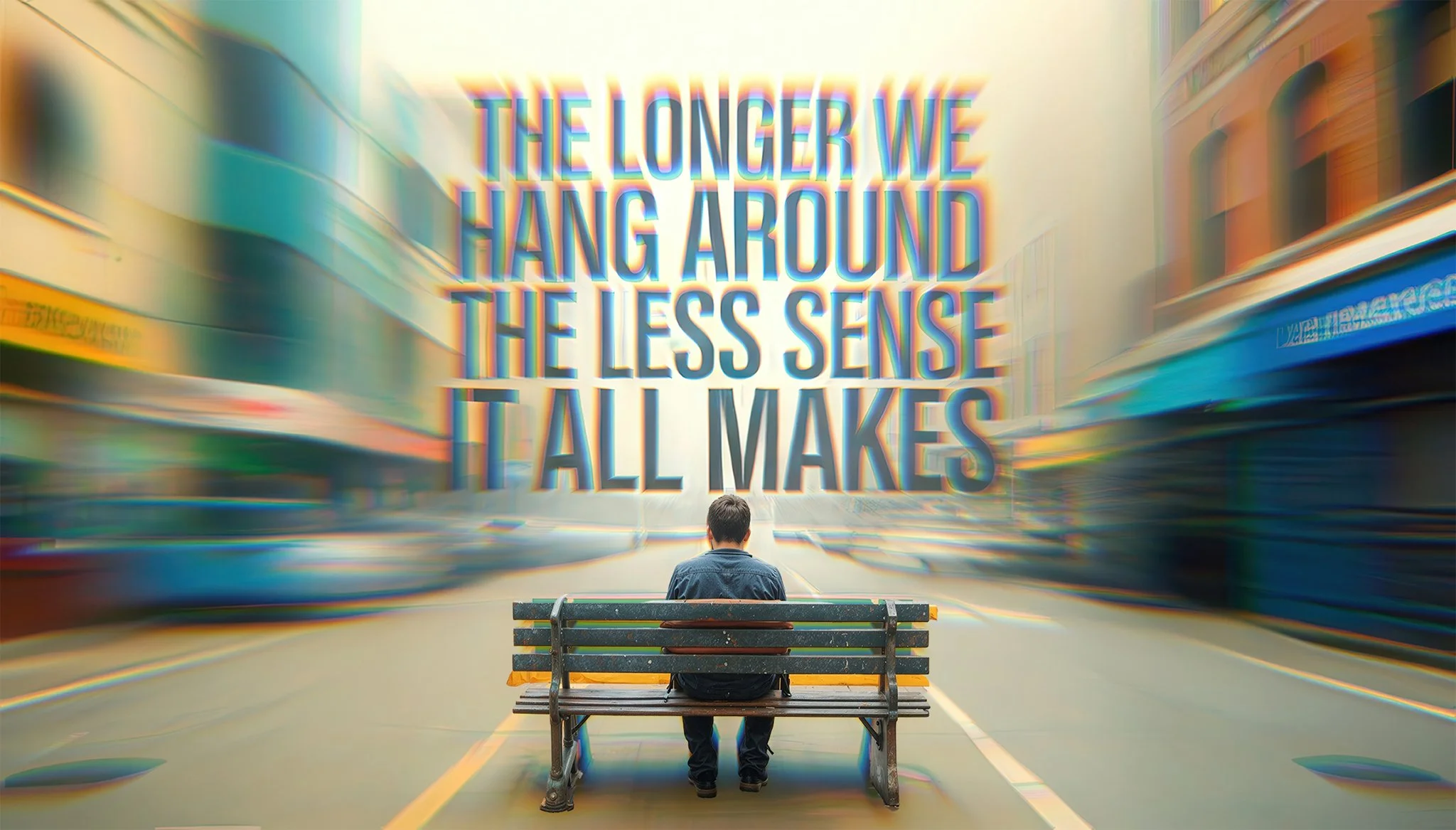

The second story is about a family standing beside a loved one who had just passed and they witness their miracle.

“In the late ‘90s my grandmother died. That of course is no miracle, just a first encounter of a fact of life. But her passing was from old age, a life well lived, and as such there was a heads up of sorts: a slow decline, a loss of facilities, a hospital, and eventually hospice. While she was in hospice my father and his three sisters were all there, as the nurses had given them the “it’s time to say goodbye.” Just after she passed, they saw visibly a gaseous like essence rise and swirl above her, swirl faster and then fly off up through the ceiling and out into the great unknown. They all corroborate this story. We all came to learn it is called an astral body, and they are observed from time to time in moments of death.

While I was not there, I was at the time a teenager - a pretty skeptical and guarded one at that - and prone to an atheistic worldview… I still am, but it forever changed me… into the first adult realization that none of this is as it seems, and the longer we hang around the less sense it all makes…”

This story brought me back to my own father’s passing, and how something similar had happened. I can’t say if it was a miracle, yet I experienced something extraordinary. For the story I again made a digital photocollage and a video. The still image is of a young man sitting in a blurred-out cityscape, his back to us, and the words hovering above him- “the longer we hang around the less sense it all makes…”

The video was completely AI generated, and I don’t think I could have been done any other way. I used numerous text prompts to arrive at the final product, and throughout its making was completely surprised by what was being generated. The process was like treading through the uncanny valley of AI, filled with unexpected hallucinations and imagery. Yet through the text prompts I arrived at the revelatory artwork I wanted and could not have dreamt up on my own. I’m not sure about its true authorship and still am thinking about these questions concerning AI. But I felt for Making Our Miracles, it reflects Cansu Waldron’s thought in her curatorial statement, ‘The machine reveals what’s hidden: a universal language of faith, gratitude, and wonder. And perhaps that is the greatest miracle of all- not that AI has learned to create, but that it has learned to listen. It reflects the light within us back to the world, weaving connection, and bringing us closer than we’ve ever been.”

Making Our Miracles began with my interest in the 1980’s when I first encountered Southwestern ex-voto painting. Since then, I had always wanted to make a project from my affection for devotional art. So it has been a gratifying having it manifest into a wonderful collaboration with Cansu Waldron. Our projects acceptance into The Wrong Biennale allowed us to work with a talented cohort of diverse international artists. Their creative practices are all uniquely different and sophisticated, representing a range of digital art methodologies. It is one of the strengths of the exhibition. I thank them all for the seriousness with which they approached their work, and how they honored the storytellers with the gift of their art.

Reflections By Curator Cansu Waldron

When Clayton Campbell approached me about this project over a year ago, I was immediately excited because it depended on openness and vulnerability from people around the world, handled with care by talented artists. I didn’t know much about ex-voto paintings before this — I had seen a few by Frida Kahlo — but I have always loved hearing extraordinary stories from friends. Creating an opportunity for these small magical moments to have a spotlight felt right.

One of the most beautiful aspects of this project is that miracles are often shared only with family and close friends — rarely with a wider community. People may dismiss your “miracle” as coincidence, even though deep in your heart you know it was a nudge from your ancestors, the universe, God, or whatever you call it. That’s why we hosted the open call anonymously — to remove hesitation and reservation.

Similarly, cari ann shim sham* noted the generosity of the framework: “being trusted to follow intuition, spirituality, and care. It felt less like an exhibition and more like a shared altar.” It has been beautiful.

What stood out to Jason Scuderi was the layered authorship: “the original artist who conceived the project, the individual who submitted the story, and my own interpretation and execution. Seeing how those perspectives aligned — or subtly diverged — created a compelling multi-view narrative structure.”

Stacie Ant

Another aspect that excited me was asking artists to create from something external — not their own experiences or emotions, but someone else’s sacred moment. Jason shared, “For Making Our Miracles, the narrative component was provided through external story submissions rather than originating from me, which made it challenging to reinterpret and restructure the work using someone else’s source material.” Yet every participating artist approached their stories with such care and devotion that the outcomes feel intimate, never cold.

One of my favorite moments was receiving two sides of the same story. We were entrusted with a same-sex love story that felt judged, hidden, heavy — yet right. We also received a submission from a mother whose son came out as gay, shattering her faith, her religion, and her belief in a God who would not accept her son. Seeing both perspectives was powerful — a miracle for each in different ways.

“It was a summer day, during a family holiday, when my son told us he was gay. He had carried the weight alone for so long, and finally, he couldn’t anymore. His father and I had no idea. It was twenty years ago — Turkey, Muslim, a society where even God was said not to accept him. That day changed everything. I felt so many things at once; confusion, grief, anger, embarrassment. It felt like a death at first, like I had lost something I couldn’t name. But over time, those feelings gave way to something deeper: compassion, understanding, love. I lost my faith in God during that time. If God couldn’t accept my son, I couldn’t believe in Him anymore. My son stood on one side, and the world on the other — and I had to choose. It wasn’t easy. Nothing was. But I chose my son. Looking back now, I see that moment as a miracle. Because it transformed everything. My love for him grew deeper, truer. That summer, something hard and hidden became honest and open. That is its own kind of grace.”

Clayton Campbell

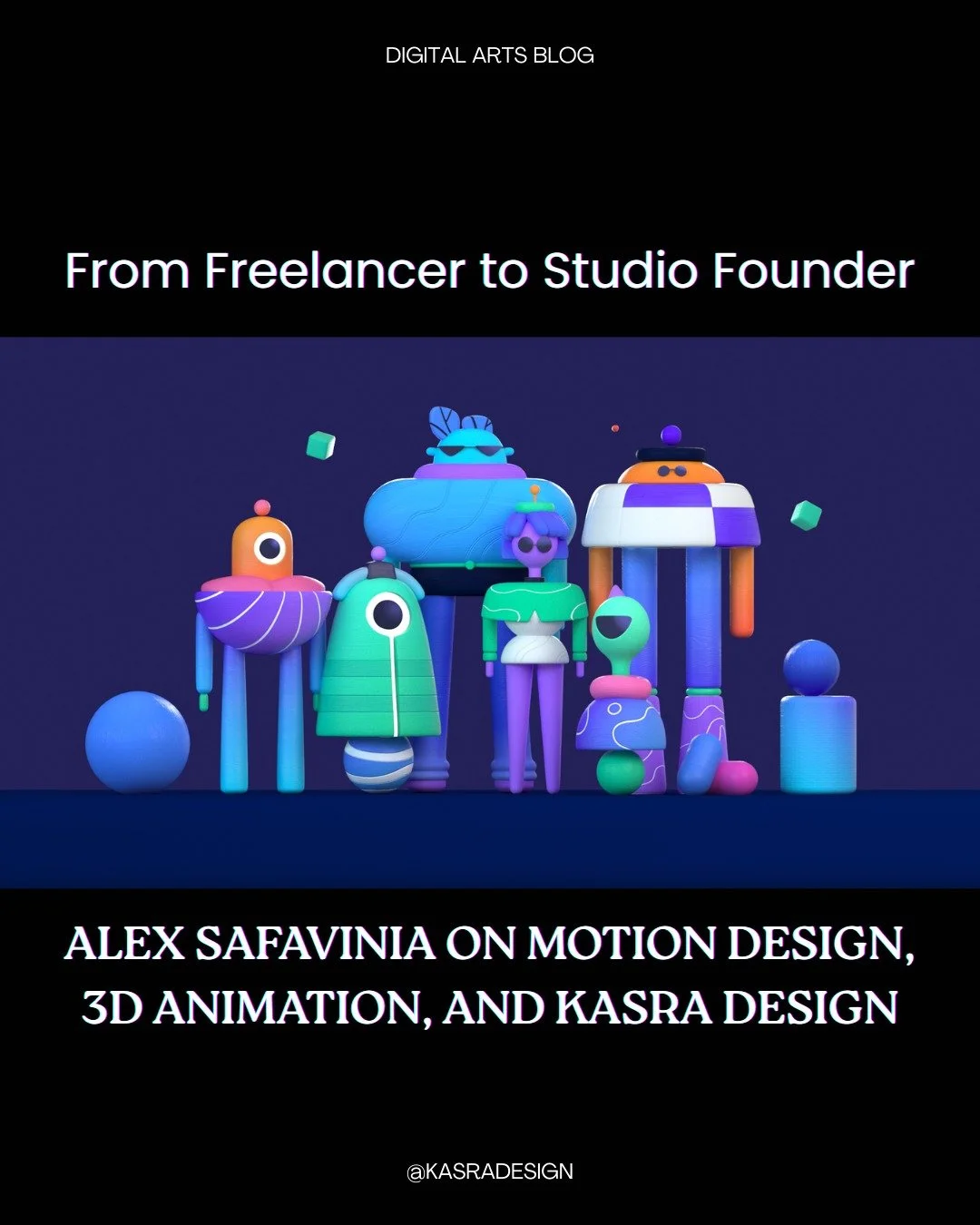

Following the success of We’ve Been Dreaming of a Magical Jungle, which I curated for The Wrong Biennale 2022–23, we confirmed with David Quiles Guill that DAB would organize another exhibition for the festival’s 2024–25 edition, focused on AI. That’s why we decided the first edition of Making Our Miracles would feature ex-votos created using artificial intelligence, with hopes that future iterations will explore other forms of digital art such as collage, illustration, and more.

Inviting artists to participate is always my favorite part of curating — especially for this project. I approached artists with open hearts, distinctive styles, and unique uses of AI. The five artists we worked with form a dream cohort.

cari ann shim sham*’s art evokes witchcraft and ancient ritual. Her generative movement practice offers a feminine and sacred approach to contemporary miracle stories. I was eager to see her interpretation of “movement as a digital ritual; XR as a healing space; and AI not as a shortcut, but as a devotional, slow, transformative tool — as oracle.”

“The biggest surprise was returning to self-portrait material from 2023 and realizing it wanted to become the core figures of the work. The project folded time back on itself.”

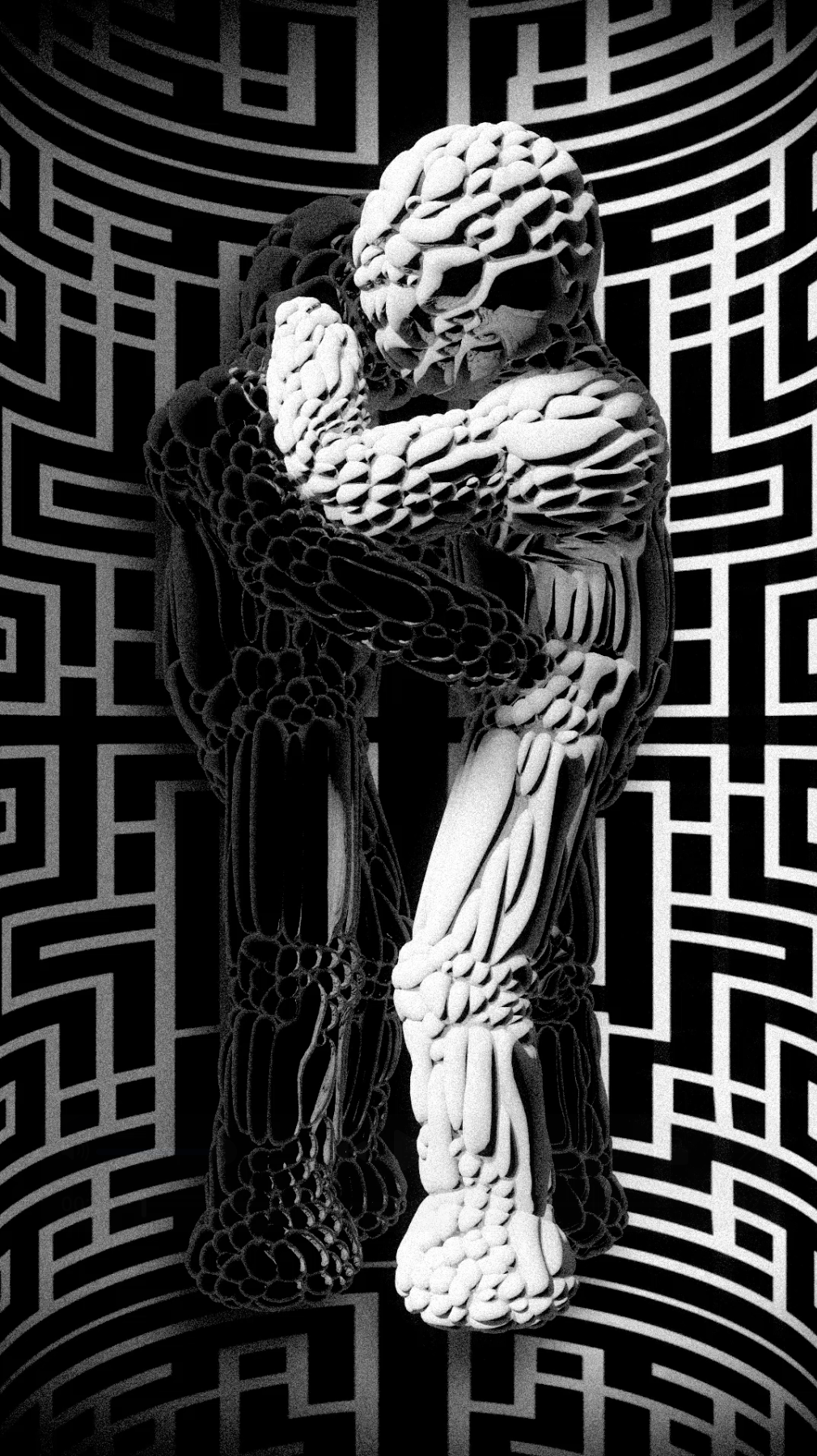

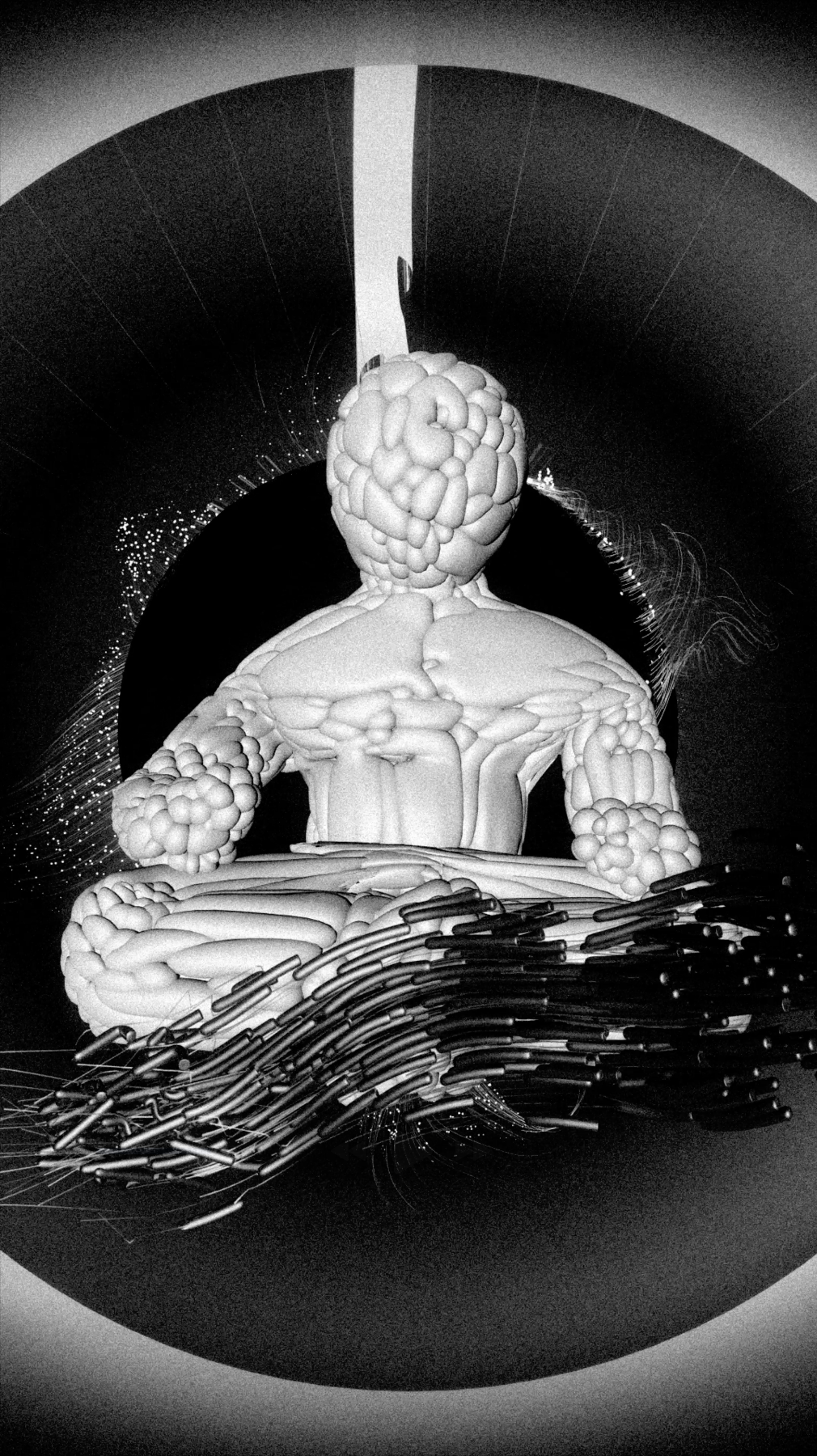

Gzhenka’s Fun House’s eerie, uncanny aesthetic invites viewers into a dreamlike world that can shift into nightmare at any moment. Her moody grayscale palette offers a darker yet compelling perspective on miracles.

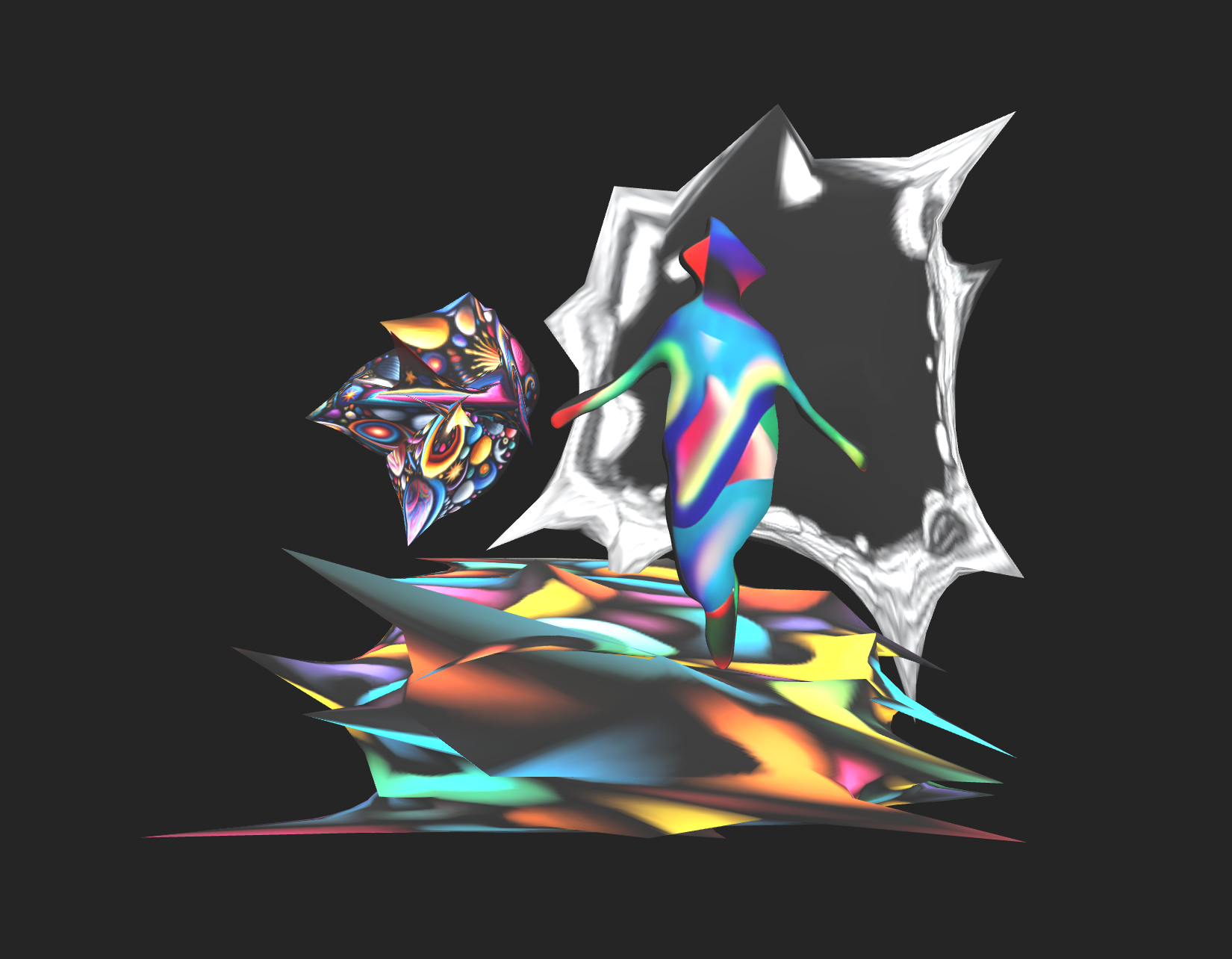

I was really excited to see what Stacie Ant would bring to the project, because she’s the playful 3D art creator of the cohort, bringing a fun, colorful, and humorous twist featuring otherworldly characters.

“I wanted to honor the original miracle stories while staying true to my art style. That tried to be challenging, especially when the stories took place in real locations and mentioned specific cities.”

Vince Fraser brought these global miracle stories to life through an Afro-surrealist lens that feels both futuristic and ancient, traditional and innovative. Placing these personal experiences in a world that's both alternate and deeply rooted in culture created a unique, powerful narrative.

“The variety of work from the artists [stood out to me,] which was refreshing.”

Lasergun Factory’s minimalist approach to art, especially through his PPL series, is all about telling complex stories with simple shapes and figures. His work in the collection captures those deep, transformative moments of change in a way that’s both understated and powerful.

“For this project, I merged the concept of Making Our Miracles with my ongoing series PPL. PPL explores humans represented as primitive, abstract figures navigating digital existence as we integrate with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence. The series reflects a contemporary view of humanity’s digital evolution and draws inspiration from artists like Keith Haring and KAWS, who used simplified human forms to express emotion and shared experience. Within this framework, AI functioned primarily as an ideological lens rather than a direct technical tool. It informed the conceptual tension of the work—humans simultaneously integrating with AI while actively shaping and training it—rather than appearing as a visible or literal application within the exhibition.”

In total, participating artists used over twenty software tools to create animations, write code, and generate visuals. The collection reflects the meticulous care and heart invested in these sacred stories entrusted to us by strangers worldwide.

One of my favorite curatorial decisions was assigning the same story to all the artists. It allowed audiences to see how differently each artist’s mind works — how one story can unfold in countless visual languages. It was important to show that the artists did not simply input miracle stories as prompts into AI generators, which can be a common misconception in a project like this.

As Making Our Miracles enters its final weeks, what lingers most is not only the artwork itself, but the trust that made it possible. Strangers shared vulnerable stories. Artists translated them with care. AI became a tool — sometimes unpredictable, sometimes revelatory — in service of something deeply human. The exhibition reminds us that collaboration is its own kind of miracle: layered, emotional, and alive. If this first edition has taught us anything, it is that when storytelling, art, and technology meet with sincerity, something meaningful happens, because people choose to connect.

On view through March 31, Making Our Miracles can be experienced online, with the full exhibition catalog available for download.

Read more:

What We Carry Into the Future: Culture, Religion, and Rituals in the Digital Age