Photo Obscura: The Photographic in Post-Photography by Natasha Chuk | Learning from Photography to Shape Digital Art

A few weeks ago, I received an email from Natasha Chuk, a media theorist, researcher, and writer whose work I’ve followed for years. Our loyal readers might remember her from our review of the exhibition 404: error, which she curated. So you can imagine my excitement when I saw her name in my inbox introducing her new book, Photo Obscura: The Photographic in Post-Photography (Intellect Books, 2025). She kindly sent me a copy, and I devoured it in a couple of hours on the train to the city. We later got together over a video call to talk about it in depth.

Photo Obscura draws on photography history, media studies, visual studies, art history, and the digital humanities. It argues that the transformation of post-photography is not just a trend but a significant movement that redefines photography by integrating it with emerging technologies and creative practices. The result is a new kind of work that may not even resemble photographs but still retains a photographic influence. The book is structured around eight chapters, covering themes such as AI-generated images, the intersections of digital and physical art forms, and the changing relationship between visual representation and perception. It includes in-depth discussions of artworks by Richard A. Carter, Stephanie Dinkins, Snow Yunxue Fu, Carla Gannis, Pascal Greco, Claudia Hart, Auriea Harvey, Sophie Kahn, Ida Kvetny, Lev Manovich, Maria Mavropoulou, Rosa Menkman, Colette Robbins, Penelope Umbrico, and Diana Velasco.

“As images become infinite and untethered from cameras,” the description reads, “Natasha Chuk traces the evolving influence of photography in a world saturated with digital art.” The book offers a much-needed reflection on the radical transformations of photography in the digital age, where AI, computational media, and hybrid art practices challenge traditional definitions of the photographic image. Moving beyond nostalgia for analog or the simple embrace of digital, Photo Obscura positions post-photography as a movement reshaping our visual culture. It is a movement in which images may no longer look like photographs but remain deeply influenced by photography’s logic and history.

Through detailed discussions of key artworks and artists, the book explores themes such as AI-generated imagery and the blurred line between representation and perception. Grounded in art history and media studies, Photo Obscura offers a new outlook on photography’s evolving role in contemporary art. It feels particularly relevant to students, artists, and scholars of photography, digital arts, and visual culture, as it redefines what it means to see and believe in an era of infinite images.

What I love most about this book is that it is not about announcing that photography is dead. It is about what we have learned from photography and how those lessons continue to evolve. In today’s culture, we are quick to declare the death of things. Television is dead. Cinema is dead. There is always a rush to find the next new thing before it becomes old news. Chuk’s approach is refreshing. She gathers critical writing, historical research, and contemporary artworks to show how digital art continues the photographic way of thinking and seeing, and what that brings to critical thought.

Natasha Chuk has never considered herself a photographer. She holds a PhD in Philosophy, Art and Critical Thought, an MA in Media Studies, and a BA in Cinema Studies. She currently teaches courses in film, photography, video game studies, media art, art history, and media theory at the School of Visual Arts and Parsons in New York City.

“I study media objects as systems of language, creativity, and persuasive power and think about how they shape and reshape visuality, geographies, publics, and ways of being. Overall, I am interested in how we understand the world phenomenologically and through our tools and practices, and the ways individual, collective, social, and political identities and behaviors are imagined, performed, and perceived through creative systems.”

When I mentioned how many people see AI image generation as mysterious or even threatening, she referenced Lev Manovich and his idea that “speed creates magic.” Analog photography was slower, so you could understand how things came to be. Today’s digital technologies move so quickly that we no longer understand how our phone cameras or VR headsets or interactive platforms work, and that sense of not knowing becomes its own kind of enchantment. Chuk’s book feels like an attempt to demystify these technologies by showing that much of their inspiration, technical logic, and meaning are not as new as we think.

One of the points she makes early in the book that stayed with me is the idea that AI images are a form of data visualization. It reminded me of projects I did in school, collecting weather data and turning it into charts to show climate patterns. When AI generators pull data from the internet to understand what a tree looks like before creating their own version, that is also, in a way, data visualization. When I told her this resonated with me, she asked, “But aren’t all images data visualizations?” She explained that light itself is information, and that is why better cameras produce better images. They capture more data. Every image is a construct.

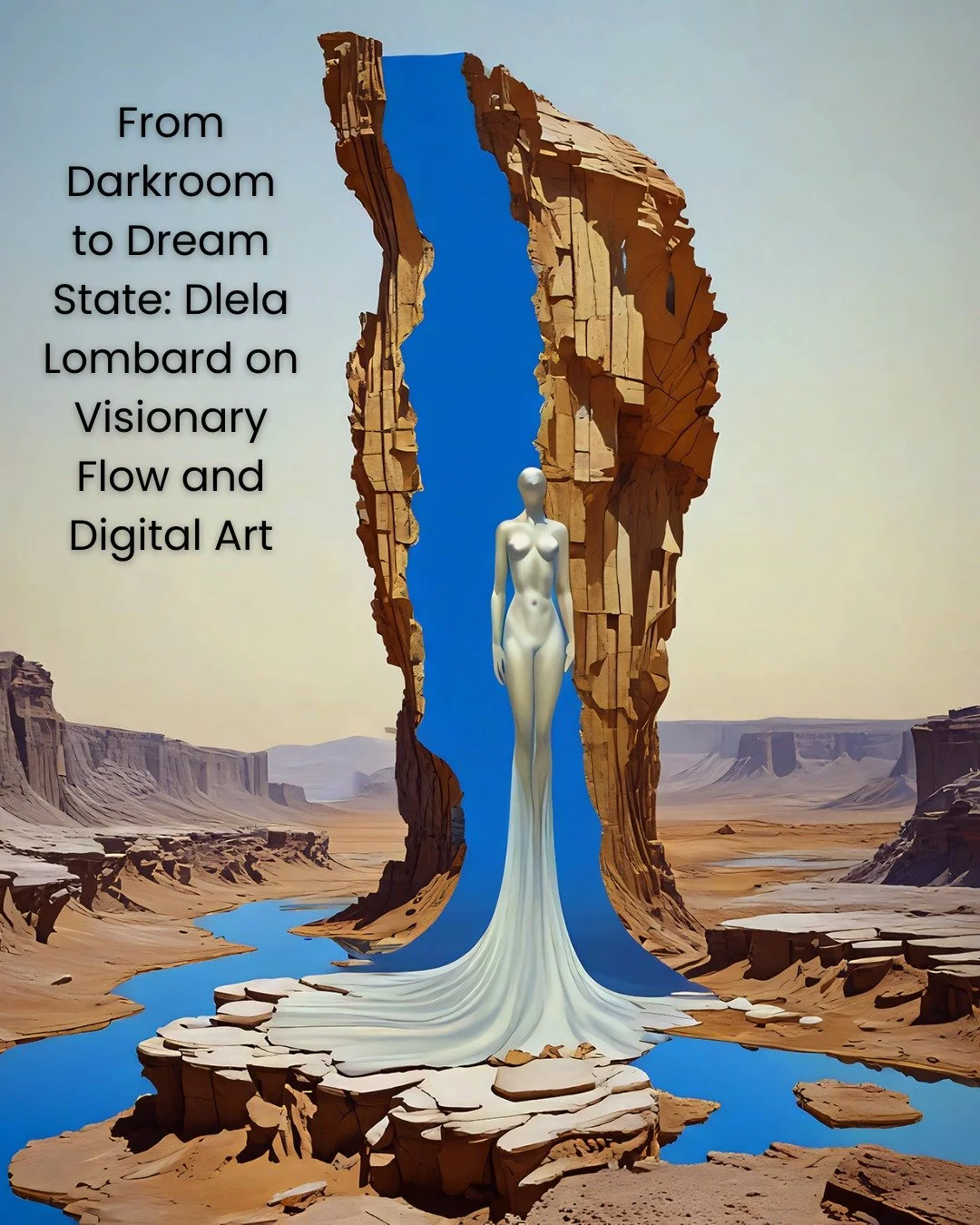

We also talked about cameraless photography, which is not new at all. Before digital tools, artists were already making photograms, cyanotypes, and other works where light directly interacts with material surfaces. These early experiments stripped away the camera and revealed photography’s true essence: light recording information. So the current fascination with cameraless, generative, or computational images is part of a much longer history.

This led us to the idea of “index reality,” which comes up often when people discuss generative AI. In traditional photography, the index refers to the trace of reality that light leaves on film or a sensor. With AI, that trace becomes abstracted and constructed. But even analog images were never pure reality. We behave differently when photographed or filmed. Fashion and staged photography are designed for the image. The question of whether something “captures reality” might miss the point because every photograph is a performance of reality.

One of the most compelling examples in the book is the work of Maria Mavropoulou, who creates imagined images based on her family’s oral and written archives. Her family albums were lost, so she uses AI to generate what they might have looked like. The results are deeply photographic but not quite photographs. They feel like memories reconstructed out of language, absence, and imagination.

During our conversation, Chuk brought up her fascination with poetry and how the tension between expressive and communicative language parallels what happens with images. Images, like poems, have the power to persuade and to shape stories. A story changes when people tell it, but that does not make it untrue.

When I asked her about her favorite chapter in the book, she said the one about video games has sparked the best discussions with her students. It looks at digitally rendered landscapes, abstraction, and how artists like Snow Yunxue Fu and Pascal Greco use virtual spaces as extensions of memory and perception.

Fu’s work, for example, draws on memory, where certain parts are forgotten or blurred, yet that makes them more emotionally truthful. Greco, on the other hand, uses the photo mode function in Death Stranding to reimagine analog and digital landscape photography. These images dematerialize the photographer’s presence. Greco’s practice turns the act of wandering in a game into a form of visual memory-making. You walk around and take screenshots that become personal memories because you spent time there.

In one of my favorite lines from the book, Chuk writes, “Photography was among the first to abstract the world in a dramatic visual fashion, showing it in fragments selected by angles, framing, proximity, thus distorting space and time.” Digital media continues this process, but with new tools that extend the abstraction further.

When I asked about the many terms circulating for AI photography, such as “syntography,” she said she prefers “post-photography” because of its historical grounding. Others call them virtual photos or screenshot photos, as well as a dozen other terms, and she says that all of those are fine – we’re just hoping to define something while at the same time trying to make sense of it.

Tying this back to Jacques Derrida’s discourse on how the thing itself becomes fictionalized as soon as it is put into language, Chuk highlights that there are no perfect lines or neat categories. The book is not about final answers but about collecting critical thought around the digital art world we are building, and how photography and all that we learned from it continue to find their place in new ways.

Finally, Chuk told me she sees this book as being especially for photographers. Digital artists, she said, already know who influenced them and what legacies they are building on. They are aware that their work grows out of older practices. But photographers often do not realize how much of what they do still informs digital art today and how they can easily expand their practice into the field of new media. Photo Obscura is a bridge between those worlds, showing how the photographic continues to shape how we see, imagine, and create.

Photo Obscura presents photography as a foundation we continue to learn from — lessons about framing, perception, memory, and light that now enrich digital art in countless ways. Chuk shows how the photographic mindset carries forward into AI, virtual landscapes, and hybrid practices, helping us make sense of new tools while keeping us connected to what we’ve always known about seeing and imagining.

Read next:

When does photography become digital art?

10 Digital Artists: Photography Meets Digital Art