Di Lu on Duality, Emotional Memory, and the Courage to Let Work Get Messy

A long-form interview exploring process, tools, influences, and the realities of working in contemporary digital art.

By Vanessa Santuccione

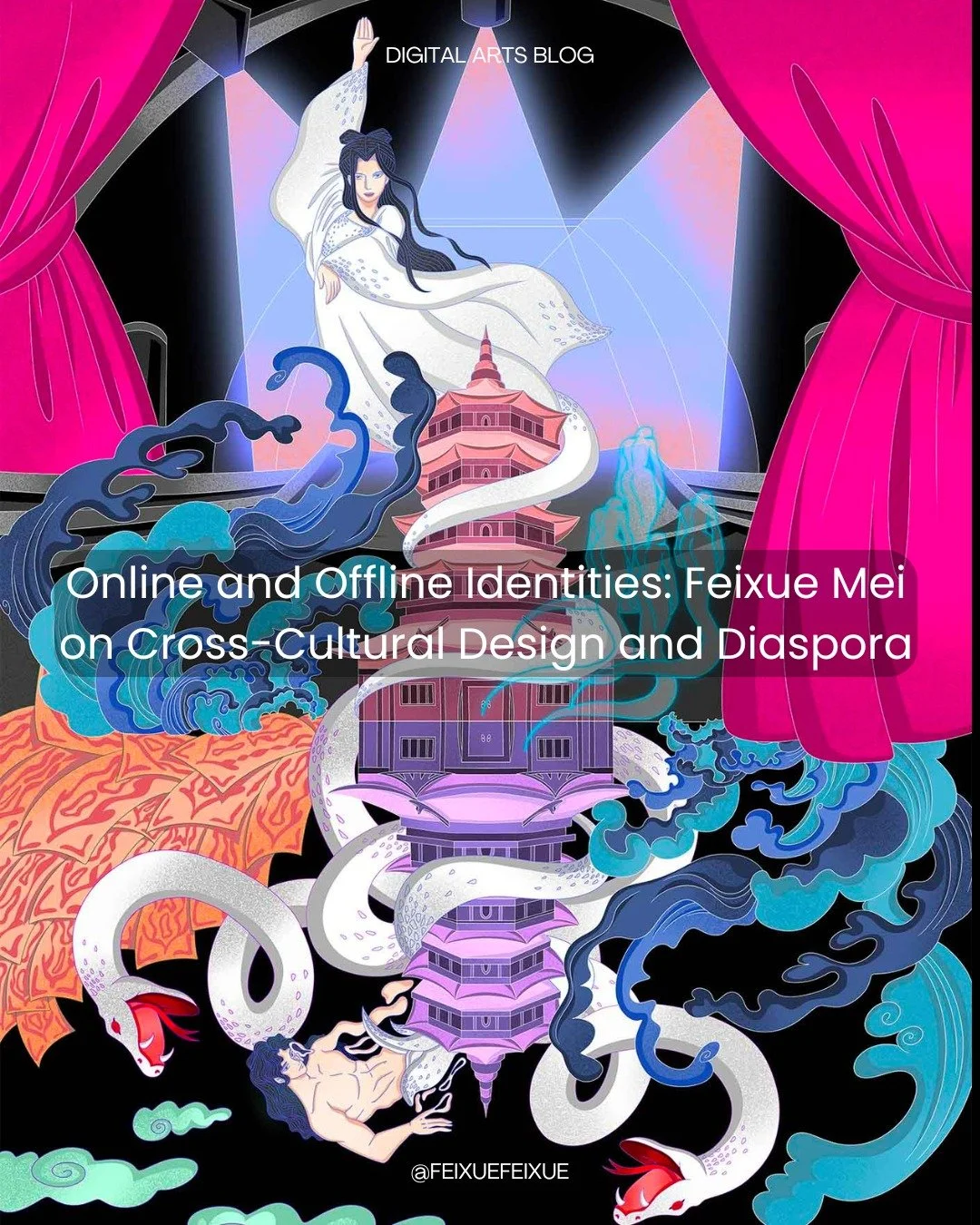

Di Lu is a visual designer working between Los Angeles and Beijing. Her practice sits at the intersection of design, culture, and storytelling, spanning typography, books, installations, and digital experiences. Moving between these two cities has shaped both her worldview and her visual language — one grounded in history, responsibility, and depth, the other fueled by experimentation, play, and creative risk. This constant negotiation between cultures shows up in work that feels poetic and emotional, yet bold and slightly off-balance.

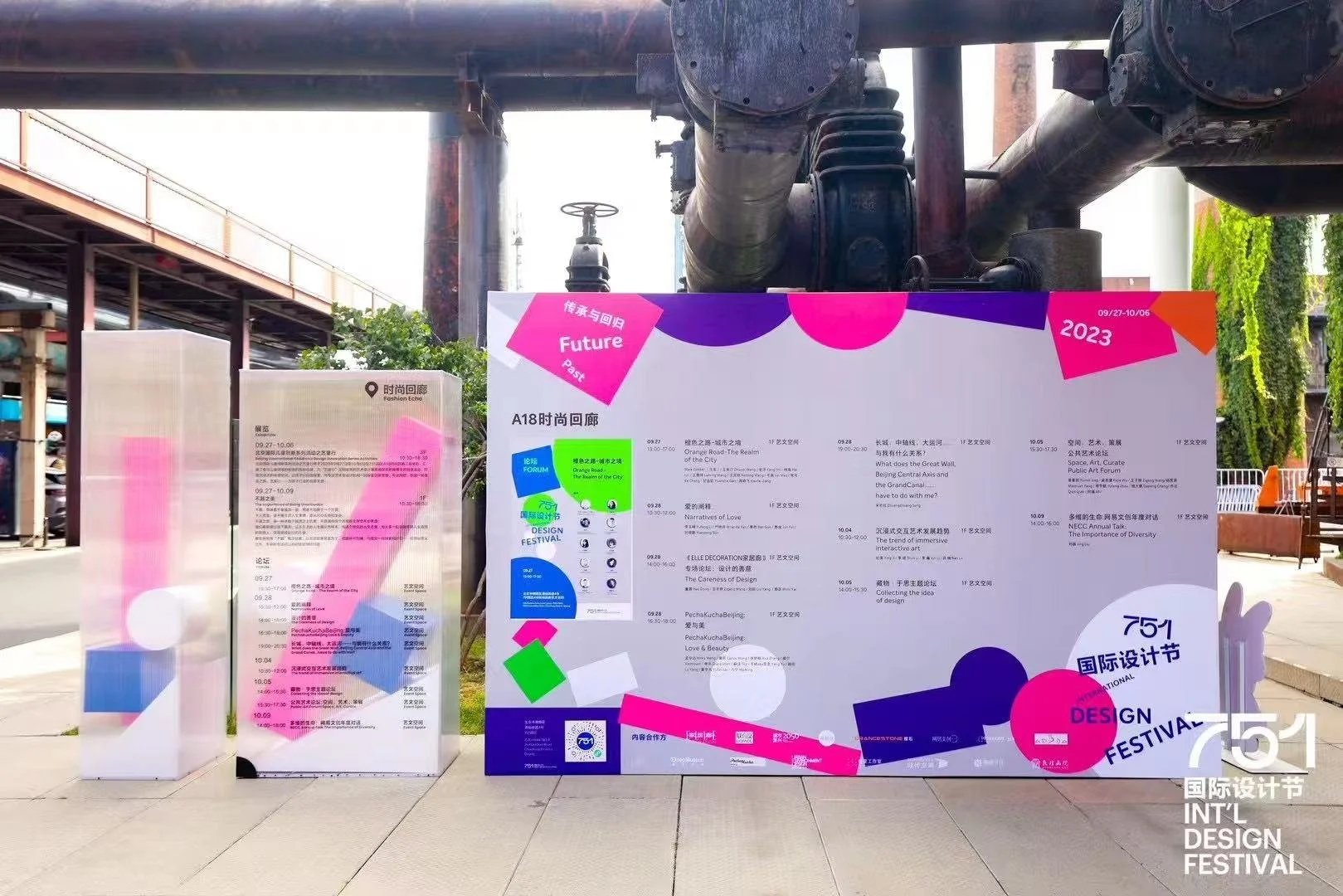

Di Lu’s projects often translate big, abstract ideas into visuals that feel human and expressive. She has exhibited internationally and received awards including the iF Design Award and the A’ Design Award. Whether crafting visual identities, building immersive experiences, or contributing to international design festivals, her work reflects a curiosity-driven approach and a belief that design is a living conversation shaped by movement, contrast, and the freedom to evolve.

We asked Di Lu about her art, creative process, and inspirations.

You mentioned that you're a visual designer working between Los Angeles and Beijing. How do you perceive the cultural differences between the two cities, and how do they influence your work?

Splitting time between Los Angeles and Beijing constantly reminds me that identity is fluid.

In Beijing, you grow up surrounded by history, family expectations, and a more collective understanding of success. People care a lot about how your choices reflect on the family, so there’s pressure, but also a sense of responsibility and belonging.

Los Angeles is almost the opposite — people are comfortable being weird, experimental, and imperfect in public. You’re encouraged to try first, fail loudly, and adjust later.

Both environments shaped me.

Beijing taught me depth and perseverance; LA taught me freedom and play.

So I naturally gravitate toward work that feels poetic and emotional, but also bold and slightly off-balance — like a visual negotiation between two worlds I’m constantly moving through.

You've received prestigious awards such as the iF Design Award and the A’ Design Award. What advice would you give to aspiring digital artists who are just starting out?

I’d say: don’t chase aesthetics too early.

Start by asking yourself what you actually care about, and build from that.

Styles change fast, especially in digital art.

But curiosity is sustainable.

If you’re making work just to look “cool,” it gets tiring very quickly.

If you’re making work to answer a question, process a feeling, or understand yourself a bit better, the work stays alive for longer.

And honestly — be patient with yourself.

Most breakthroughs are built on a pile of very “ugly” experiments that no one sees.

What’s a dream project you’d love to create someday?

I’d love to build an immersive installation that feels like stepping into someone’s subconscious — a space where mythology, technology, and emotional memory bleed together.

Not in an overwhelming “spectacle” way, but in an intimate, cinematic way.

Something you don’t just look at, but quietly feel in your body — like walking through a memory you didn’t know you had.

I truly felt the power in your artwork Shadows in Socialization. Could you share what inspired you to create it and how it connects to your personal experience?

Shadows in Socialization grew out of my own experiences with social bullying and the long shadow it casts into adulthood.

As a child and teenager, I went through moments of being excluded, mocked, and subtly targeted — nothing dramatic enough to be a headline, but persistent enough to reshape how you see yourself. It’s the kind of bullying that hides inside jokes, group dynamics, and small daily humiliations.

When you’re young, you don’t have the language for it.

You just slowly learn to read the room too carefully, to anticipate danger, to stay smaller so you won’t be noticed. That’s where social anxiety starts: not from “being shy,” but from being trained by experience to associate visibility with risk.

For this piece, I worked with my own childhood materials — diary entries, letters, school notes, photos, and small “evidences” I kept almost instinctively. At the time, I didn’t know why I was keeping them. Later, I realized they were a record of how I was trying to make sense of what was happening to me.

Transforming these private archives into a visual work was both painful and healing. It was a way to say:

Yes, this happened.

Yes, it shaped me.

But I get to decide what it becomes now.

The piece isn’t about staying in the role of a victim. It’s about tracing how early experiences of being diminished can grow into social anxiety, self-doubt, and hyper-awareness — and then gently, slowly, turning that sensitivity into a form of understanding and empathy.

For me, Shadows in Socialization is less about re-opening old wounds and more about finally giving them a language and a shape, instead of just carrying them silently.

Could you tell us about some of your favorite pieces or a past/upcoming project? What makes them special to you?

One piece I care a lot about is a two-sided mixed-media work called “Duality.”

The front is very detailed — layered textures, hints of classical imagery, and a figure that feels almost mythological. The back is much more stripped down and contemporary, like the same soul seen in a different era.

For me, the two sides represent inherited identity versus self-constructed identity:

what you’re given, and what you slowly choose.

It feels special because it’s vulnerable without being overly dramatic. There’s tension in it, but also humor and tenderness. It reflects the feeling of being in-between cultures, generations, and expectations — not fully one thing or another, but something constantly in motion.

Are there any artists or creative influences that have had a significant impact on your work? How have they shaped your artistic style or approach?

I’m drawn to artists who deal with psychological landscapes —

people like Louise Bourgeois, Henri Matisse, and Cai Guo-Qiang.

Their work made me believe in visual metaphor as emotional architecture:

a color can hold grief, a shape can hold desire, a material can hold memory.

I don’t try to imitate them, but I carry their courage — especially the way they allow vulnerability, contradiction, and complexity to exist in one piece without needing everything to be “resolved.”

How do you handle feedback and critique of your artwork? Can you share an example of a time when feedback helped you grow as an artist?

I try not to fuse my identity completely with my work — otherwise feedback feels like surgery.

Someone once told me, “Your work is expressive, but you’re still a little afraid of letting it get messy.”

At first I was defensive, because I liked control and polish. But they were right.

When I allowed more risk and “failure” into the process — more rough edges, more experimentation — the work became more alive and honest. It started to feel less like design created to impress, and more like a language that could actually hold complicated feelings.